Why can’t you be (c) Samantha Groenestyn (oil on linen)

I persist with Deleuze because, like me, he cannot let go of the physical, sensuous nature of painting, the way the body permeates painting, invigorates it, enlivens it. Should we think of painting as a process, says Deleuze (2003: 160), it is one of a ‘continual injection of the manual … into the visual,’ and this claim stresses that painting is both active and bodily, even though it belongs to the visual domain. Painting thus offers us an unexpected opportunity to extend our idea of the visual, precisely because it exists in the overlap of hand and eye. Deleuze (2003: 161) suggests it might help us overcome the duality of the optical versus the tactile. Painting that is haptic subordinates neither hand nor eye, but through it ‘sight discovers in itself a specific function of touch that is uniquely its own’ (Deleuze, 2003: 155).

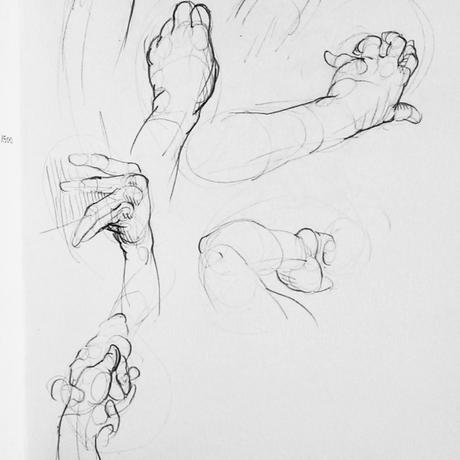

The hand, argues Deleuze (2003: 154-5), can surface in painting in different ways. It might be completely subordinated to the eye and hence merely a limp tool of an ‘ ‘ideal’ optical space’ (Deleuze, 2003: 154). In this case, ‘the hand,’ he (Deleuze, 2003: 154) forebodingly pronounces, ‘is reduced to the finger.’ This makes it, naturally, digital, which carries some lingering echo of Goodman (1976: 121; 160), no less for linking the discrete, pulsing, on-off series of digits with a code. Optical space proceeds by way of cerebral systems that make sense of and organize forms by way of an ‘optical code.’ But there is an optical space which incorporates some manual qualities such as depth, contour and relief, and we could call this a tactile breed of the predominantly optical space (Deleuze, 2003: 155). But when the hand takes precedent, in a frenzy of unthinking action, we are confronted with the manual. Form is obliterated and the eye is ravaged by roaming, nonsensical marks (Deleuze, 2003: 155).

Abstraction takes the intellectual high-road and develops an optical space that stills the quivering hand as much as possible; abstract expressionism, at the opposite extreme, aims for pure, sensuous but senseless physicality (Deleuze, 2003: 103, 104). And then there is Francis Bacon. Indeed, what should we call these pockets of directed fury, these tangled ferments of wildness carefully hemmed in by neatly landscaped contours? For Bacon, the code remains in the brain and fails to electrify us, it fails to directly jolt our nervous system because it is devoid of sensation. But the purely sensual is desperately confused. Bacon represents a third way, argues Deleuze (2003: 108-110), a way that pumps the volatile manual into the stable visual, but in controlled doses. Bacon’s formula, he (Deleuze, 2003: 98) continually reminds us, is to ‘create resemblance, but through accidental and nonresembling means.’

This appeal to accident can be troubling, but it is precisely here that the manual enters. Two important things surface here: that the artist never confronts an empty canvas, and that her intentions are inevitably thwarted by the wilfulness of the paint. Deleuze (2003: 86; 93) explains Bacon’s reliance on chance as a method of wrestling with the ‘givens’ in the canvas—which can encompass everything from figurative conventions, the schema of photography, personal predilections and habits, and even the prescribed limits and center of the familiar quadrilateral canvas, the parts of whose surface are thus not equally ‘probable’ before the poised brush. Artists are well aware of this invisible weight, they know that the unmarked surface is laden with preconceptions. Certainly, many dutifully slather paint into their well-worn grooves; the task of an alert painter is to find a new way out of the canvas, to create something, in the rawest sense of the word. Deleuze—creator of concepts—calls the improbable creation the ‘Figure’ (Deleuze, 2003: 94), and wants to see the painter extract it out of the low drone of clichés.

Bacon’s (seemingly misunderstood) way, as elucidated by Deleuze (2003: 156), is to seize upon chance. The method is simple: Start with the figurative form, with the intention to represent some particular thing or person, and thwart the representation by permitting the hand to become possessed. The chaos of the manual is invoked but carefully contained within the contours of the form; chance is permitted to wreak havoc in a designated zone. Deleuze—creator of concepts—calls this feverish scrambling the ‘diagram’ (Deleuze, 2003: 99). The diagram is whatever the demon-hand deigns to scar the canvas with: scraping, rubbing, scratching, smearing, throwing paint at all conceivable angles and speeds; revelling, in short, in the paint itself, in its unpredictability. I would suggest this manual violence is the logical extreme of an utterly banal—though crucial—fact of painting, which is that paint is always an unknown, that there is always some disconnect between the mark the artist tries to make and the mark that she makes. The most careful stroke can slip, bending disobediently, or its edge can violate another, mingling colours that were never meant to be mingled, more smoothly and thickly in a liquid manner, or abrasively and roughly as a dry brush trespasses an intended boundary. The manual is difficult to escape, and arguably those who get their marks down where and how they want them either have a practiced formula (which does not permit of healthy artistic invention) or they have mastered that happy skill of manipulating chance (Deleuze, 2003: 94).

For Bacon’s cleaning lady, Bacon (in Deleuze, 2003: 95) concedes, could indeed pick up a brush and summon chance, but the accident alone is usually not enough. The artist must wrestle with the aberrations of paint and find a way to take advantage of them, to manipulate them and reincorporate them into her greater vision. Rather than wielding ultimate control over the paint, the artist seeks to beat it at its own slippery game. The destructive ‘scrambling’ of the hand makes a defiant challenge to the artist’s intentions, but she may seize this opportunity to craft something unexpected and new, and regain control of the painting. Painting, on these terms, consists in the delicate balance between intentions and the hiccups of reality.

The question, then, is how the artist is ‘to pass from the possibility of fact to the fact itself’ (Deleuze 2003: 160). How to move from her intention, her nascent visual idea, finding a path out of the cliché-burdened surface, navigating the hazards of accident inherent in the act of painting, to the actual image made up of physical and three-dimensional marks that fossilise her movements. Deleuze (2003: 159) insists that the measure is whether a Figure emerges from this process, a Figure which delightfully deviates from ordinary representational formulae, without dissolving the picture into painterly anarchy. This middle ground marries the two: ‘The Figure should emerge from the diagram and make the sensation clear and precise’ (Deleuze, 2003: 110). If no such Figure materialises from the manual intervention of the hand, the process has failed (Deleuze, 2003: 159). That is, the artist has been defeated by chance, the hand has supremacy, and the haptic potential of the painting is lost.

By way of example, Deleuze (2003: 156) describes Bacon’s intention to paint a bird. In the process of painting, the physical reality of the paint intervenes; the form remains, but the paint caresses it in unexpected ways and the relations between the pictorial elements change—an umbrella begins to show itself and Bacon claims this Figure instead. ‘In effect,’ Deleuze (2003: 156) explains, ‘the bird exists primarily in the intention of the painter, and it gives way to the whole of the really executed painting.’ It is not simply that the form changes, out of sheer inadequacy or laziness, but that new relations are suggested during the act, and the artist can make up her mind to seize them. Representation is achieved by another course.

The scrambling can take place without a metamorphosis of forms: a head, begun as a portrait, could equally be scrambled ‘from one contour to the other,’ triggering new relations that distance the image further and further from a likeness, indulging more and more in the paint, in the movement of the arm, until ‘these new relations of broken tones produce a more profound resemblance, a nonfigurative resemblance for the same form’ (Deleuze, 2003: 158). We are back at Bacon’s solution for fighting against the already-laden surface, a fight that incorporates the belligerence of the hand in a controlled manner.

But let us inject a little skepticism into this discussion. Perhaps Bacon has simply discovered that a convincing enough outline, with, say, recognisable ears and chin, can be ruthlessly abused without entirely losing its claim on representation. Perhaps he has found a way to intellectualise his technical shortcomings. Why should we permit him such liberties with form; why should we find something compelling in these muddied faces? Why should we indulge him this chance-driven and thus possible unskilled ‘injury’ against his sitter (Sylvester, 1975: 41)?

For a start, his whole attitude to paint is worth some attention. The appeal of paint is inseparable from a desire to paint; an image alone is never enough for a painter. There are simpler means of recording images than struggling with uncooperative and toxic substances. If one is to paint, one ought to delight in the possibilities paint affords: the tactile, unpredictable and infinitely manipulable properties that paint alone possesses. Bacon (in Sylvester, 1975: 58) certainly relishes the materiality of paint itself, explaining that in contrast to the smooth and crisp texture of a photograph, which appeals to our brain, ‘the texture of a painting seems to come immediately onto the nervous system.’

Yet this is no kindergarten, and an artist ought not simply revel in the delightfulness of paint. As a thinking, observant, functioning adult, she can harness the possibilities of paint toward some directed purpose. Bacon cares for both: he thrills at the shock to his nervous system and he demands some order and sense. He doesn’t abandon his intentions entirely, but he reconsiders them as reality turns up new possibilities, precisely because he recognises the nature of paint and the way it interacts with his own movements, his own hand. A mature artist can be expected to push the possibilities of paint, to see what new and sophisticated relations she can wrest from it. The paint is both Bacon’s opponent and his accomplice; were it otherwise for any artist, we might question their motives.

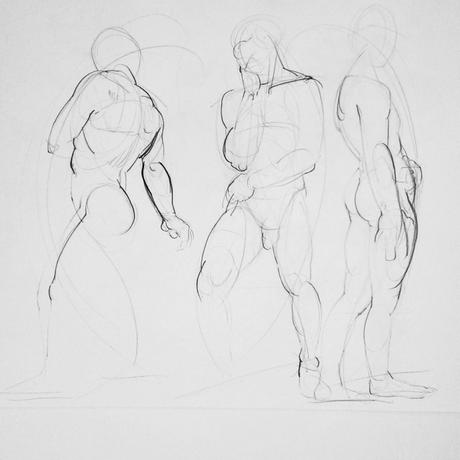

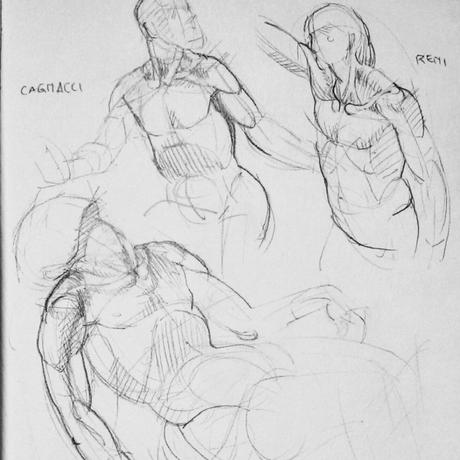

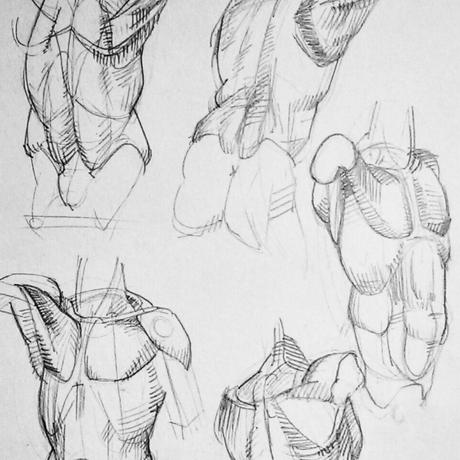

(Copy after Bammes)

Ruprecht von Kaufmann is a painter who demonstrates a similar attitude. His work can be vividly true to life, it can actively represent things and events and people, with a sensitivity to form and to light and to space. But in his most representational work, the intoxication with paint ferments at the surface; he seamlessly weaves the quirks of paint into his steady design. I would venture that he seeks out the anomalies of paint, that he dares the paint to defy him, and when he brings his immense experience to the task he subdues the unruly paint with a surprising virtuosity—giving it that freshness and agility that Bacon (in Sylvester, 1975: 120) calls ‘inevitability’—and aligns it to his purposes. His portrait series probably comes nearest to Bacon’s process: these pictures feel as if they start out guided by a clear (representational) idea, but then collide head-on with paint. Swirls and smears and heavy dollops of paint reconfigure the face, and the question that remains is whether a Figure emerges or whether each face fruitlessly suffers this violence at von Kaufmann’s hand. And so, lastly, I would argue that Deleuze’s defence of Bacon holds if we grant that it is possible to say something truer about what we see by deviating from its actual appearance. Von Kaufmann’s portraits seethe with the human qualities a person might ordinarily keep submerged under their skin; he makes brutal observations a perceptive person might make, and his brush (or Lino-cutter) gives him the means to represent them.

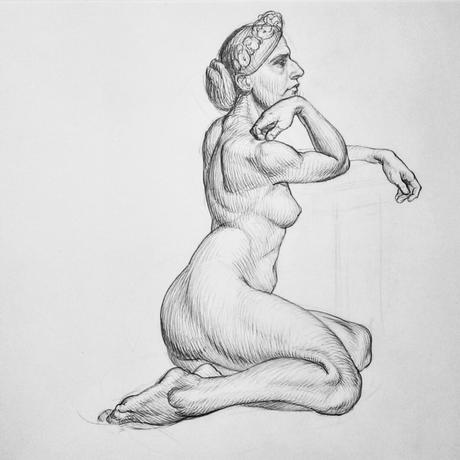

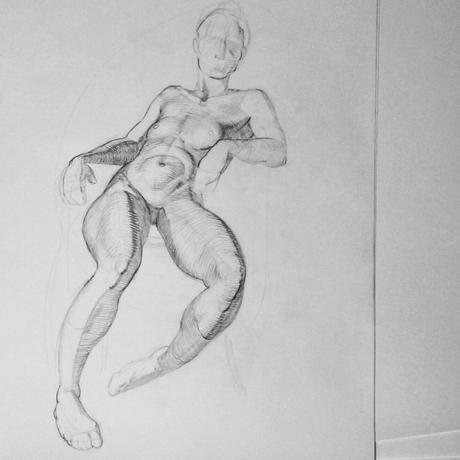

But besides this, the diagram might have less to do with chance or accident, and more to do with the parameters the artist sets for herself. My own portraits, insistently representational, refuse to satisfy the usual preferences for lighting and colouring, being rather abruptly coloured and forcefully lit, and my attention is usually absorbed in sculpting a head on the stubbornly flat surface. My sitters must be alarmed at my ungenerous attention to their bulging cheeks and their sunken eyes, to the fascinating furrows beneath their sockets and to their heartily constructed noses. The scrambling that takes place within my contours is indebted to my obsession with volume and with lively but systematic colour, color ordered by the logic of three-dimensional color space rather than strictly by what I see—my lovely, hapless model serving more as a suggestion for the complex system of the physical world I have compiled in my mind.

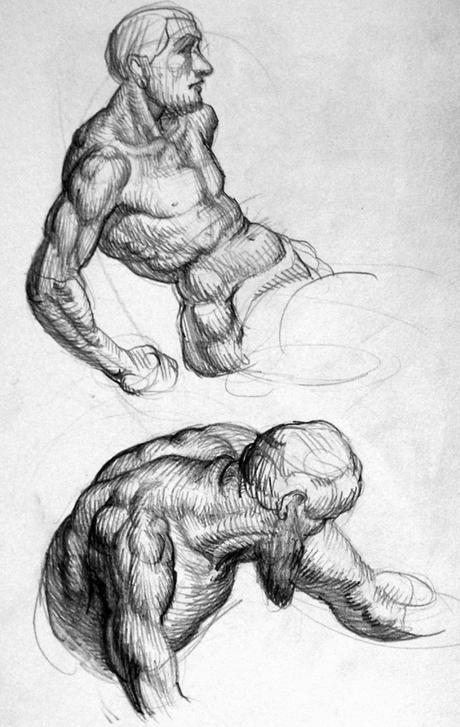

Copy after Rubens

And this brings us, finally, to language. According to Deleuze (2003: 117), Bacon’s ‘middle way’ through the digital and the manual, the abstract and the abstract-expressionist, the optical and the tactile, constructs a language out of the diagram. He calls it an ‘analogical language’ (Deleuze, 2003: 113; 117), a ‘language of relations.’ As I understand it, the painter takes hold of the actualities of paint and orders them into a fluid and manipulable system that she can use to represent strong and clear ideas. I bend paint to my ideas of volume, of the way light and color interact, but I also incorporate its temperamental nature into my system. With time, I build up a language not of symbols, but of relations of color and tone and light and texture and edge, and a thousand other things. But the versatility of this analogue, rather than digital, language, is rooted in the chaotic partnership of hand and paint. The language is rich and infinite because it is continually reenergised by the manual, non-thinking impulses that Deleuze names the diagram. Conceptions that insist on a code, on symbols, on the binary constitution of the digital, restraining the hand as the countable digit of the finger, enter a discussion with painting purely through the brain and not through the body. Goodman (1976: 234) is right to find a code too rigid and discrete for the continuous flow of paint, which must be described as analog. Deleuze distinguishes a fittingly analog language by which sensations and not symbols speak to us.

This analogical language of painting, Deleuze (2003: 118) elaborates, has three dimensions: planes, color and body. But he expresses a particular enthusiasm for colour, which guides us towards that particularly haptic painting that he craves (Deleuze, 2003: 140). He esteems colourists above all other painters for their delicious facility with the entire language of painting, for if you can sensitively modulate color and powerfully manipulate its relations, ‘then you have everything’ (Deleuze, 2003: 139). Colour incorporates tone (or value, the black and white scale of lightness and darkness)—yellow is already a lighter tone than blue; to darken it one must modulate through browns or greens, at the same time coping with neutralisation. In lightening a blue, adding white immediately neutralises it, and one must also think through the color of the light that brightens it, which might be of a stark yellow-orange, demanding a shift in hue towards its opposite. Colour incorporates edge and thus line. It demarcates planes that describe form. Tone (or value), concerned solely with the presence or absence of light, is much more straightforward: a ‘pure code of black and white,’ binary, digital (Deleuze, 2003: 134).

Tonal painters are able to achieve dramatic results by punching in their high-contrast code; the code renders their work sensible in spite of nonsensical colours. But their simpler codification of light is, argues Deleuze (2003: 133), limited to the optical function of light. It sits primly and politely in optical space and only appeals to our intellect. But color bites directly into our nervous system. Though it engages our eyes, it engages our whole body through our eyes. It wrenches us into haptic space. The language of painting, then, in all its analog complexity, in its infinite variability, its carefully modulated relations, remains rooted in the body—in both the movements of the painter and in the sting that the viewer’s raw nerves suffer. Invoking the body electrifies painting and expands our otherwise quickly-shrinking conception of the visual.

Copies after Rubens

Deleuze, Gilles. 2003. Francis Bacon: The Logic of Sensation by Gilles Deleuze. Translated by Daniel W. Smith. 1 edition. Continuum: London.

Goodman, Nelson. 1976. Languages of Art: An Approach to a Theory of Symbols. 2. ed. Hackett: Indianapolis, Ind.

Sylvester, David. 1975. Francis Bacon, Interviewed by David Sylvester. Pantheon: New York.