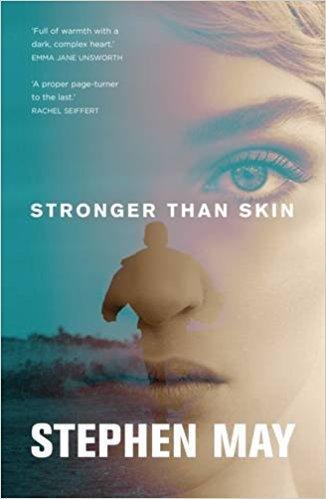

It’s a pleasure to welcome today’s guest Stephen May back to the Literary Sofa. I’m a big fan of his writing – Stronger than Skin is the third of his (four) novels to be featured here and one of the dozen excellent titles included in my Summer Reads selection.

It’s a pleasure to welcome today’s guest Stephen May back to the Literary Sofa. I’m a big fan of his writing – Stronger than Skin is the third of his (four) novels to be featured here and one of the dozen excellent titles included in my Summer Reads selection.

I’ll always be keen to read new work by Stephen, but this novel was of special interest because, like my own debut Paris Mon Amour, it involves an affair between a young man and an older woman, but from the male perspective. As many of you know, the representation and treatment of women in society and the arts/media is a big interest of mine, but masculinity fascinates me as well. I don’t think feminist beliefs or opposition to patriarchy are diminished by acknowledging that men face issues of their own. It’s something I’ve thought about a lot raising two sons, not least because in my background men built things and fixed things; all very boys don’t cry, and not without cost. Stephen specialises in opening up the inner life of men, and he has free rein to talk about that today (more of my thoughts on his novel follow in the review below):

Men. Oh yes, we know about those guys. Arseholes, most of them. Give them an inch and they’ll take a mile. Manspreading on the Tube, mansplaining at the office. Always grabbing the best seats, hogging the remote control, carefully installing the glass ceilings. Making sure they’re running things. Getting themselves elected. Getting themselves paid more. And what about all the mess they leave everywhere? The drunkenness and the violence. The debts? The abandoned kids? Even the nice ones can be a pain in the proverbial, what with the commitment-phobia, the casual pomposity, the thinking they’re God’s gift. The inability to keep it in their trousers.

And that’s not even the worst thing because, jeez, the amount of bloody droning on about pointless crap they do. Sport and cars. Football. Never any real conversation about things that matter. Never about how they feel. Men will – literally – die rather discuss their feelings, rather top themselves than admit to feeling sad, rather die of cancer than show their balls to a doctor. These days they can’t even do DIY. Don’t even seem to want to take the bleeding bins out. Why do we bother with them? What is the point of them?

Except there’s a good chance (I hope) that the men you know best are not like this. Or are only some of the above, some of the time. Your partner is not like this (or not often). Your sons are not like this and neither are your brothers. Your best mate at work is not like this. Justin fucking Trudeau is not like this.

There’s a chapter in my book Stronger Than Skin where one of the characters – Eve – explains that she thinks men should be banned from producing any art for ten years at least. They should let someone else have a go. The men take issue with her. They argue that why should they – as individuals – have to shut up simply because other, way more privileged men got away with murder in the past? Eve just shrugs ‘You can’t make an omelette…’ she says. (I should say it’s an idea I first heard proposed by my daughter.)

But you know who worries most about the point of men in the 21st century? Men do. And how do I know this? Because they tell me. We tell each other. Because one of the secrets men have is that we do talk. Properly. About the shit that matters; we just like to do it with a pool cue in our hands. Or while flipping burgers on a Barbie or playing FIFA with our kids. We like to multi-task when we’re baring our souls.

That is, I think, one of the things my novel Stronger Than Skin is about: the secret inner life of ordinary men (it’s about a lot of other things too of course: guilt, murder, sex, class, the dangers of anti-depressants, Cambridge University, the 90s, pubs…).

Stronger Than Skin is my fourth novel and I think that looking back from this distance (my first book came out in 2008) it’s becoming clear what my territory is, my little patch of turf. Anxious men from smallish towns placed under intolerable pressure and at the same time trying to work out what they should do for the best. Trying to see where they fit in a world where the old certainties are collapsing around their ears. It’s not that my characters even liked those old certainties – they didn’t even believe in the values that gave rise to them – but a world without them, where new ways of being are constantly on offer, where the world is excitingly/dangerously fluid, well, that can be difficult terrain.

There’s a new book out by the photographer Laura Dodsworth called Manhood: the Bare Reality. It consists of pictures of 100 penises – old, young, big, small, black, white – with the hundred men attached to them telling their stories. Dodsworth says that once a man has shown you his penis, he finds it easier to bare his soul. She describes the project as one that meant she found herself falling back in love with falling in love with men, with their vulnerability.

She says, ‘I had this sense that men were in a ‘man box’ as much as I’d been in a ‘woman box’, and I wanted to get to know them better and hear their stories. One word for penis is manhood, so it seemed a perfect starting point to talk about being a man.’

And I think – hope – that’s what you get with one of my novels too. A place where we can explore what it is to be a man at this point in time. Where we can break down the walls of the man box.

In my books my imagination fills the space where Laura Dodsworth puts her camera. My men aren’t always likeable, they don’t always behave well, but they’re trying at least. And in trying they reveal themselves and what they reveal is… that they’re pretty much the same as women. Struggling with a lot of the same concerns anyway.

I suppose in the end I think we are all more the same than we are different. That’s my instinct, supported by experience and observation.

It’s a confusing business because we have to take this on trust. We can’t ever know for sure. I don’t really know how my brother or my children think, never mind anyone else. I don’t even know if what they think of as ‘red’ or ‘blue’ is the same as what I mean by it, so how can I know what animates other people completely unconnected to me? And then there is the effect of patriarchy, which definitely exists and is meant to divide us. Thousands of years of evolving patterns of social control which do no one – women or men – any favours. It might be visibly crumbling, but it’s taking its time.

Nevertheless I’m in agreement with Maya Angelou. In her great poem Human Family she says ‘We are more alike, my friends/than we are unalike.’ It’s a line she repeats. And it’s an idea which runs as a kind of hopeful thread through all my novels.

You can hear Maya Angelou read the whole poem here – it’s probably the best 1 minute 46 seconds you’ll spend today.

Author photo © Jonathan Ring

Thanks to Steve for this brave and provocative piece that’s both thought-provoking and entertaining. I liked his references to work by women: Laura Dodsworth’s new book was already on my radar and he’s right about Maya Angelou’s powerful poem, with a message that is so needed in the context of recent events.

It’s safe to assume that some of you will have views on this subject and we’d love to hear them!

Novels by men consistently make up around a third of my reading, year on year, and I value having access to a range of male perspectives exposing aspects of human existence that I will never personally experience. I don’t however hold with the frequent perception that men’s writing on emotions, relationships or anything else traditionally regarded (and often dismissed) as female territory, is more inherently meaningful, laudable or noteworthy than when tackled by women*. Creating believable, rounded characters and stories which genuinely engage is a matter of emotional intelligence and humanity, not gender, and it’s not an easy task for anyone. There is no doubt that Stephen May has important and universal things to say about 21st century masculinity, but crucially, his starting point is the insight and empathy which animate his characters as individuals and make the reader invest in their complex lives, as I did in Mark Chapman’s. There is, as always, a successful synergy between May’s subject matter and his writing style, refreshingly direct but not lacking elegance. It’s his unique blend of cynicism, humor and tenderness – because there is real heart there – which leads to the touching and unusual interactions which are such a strength of Stronger than Skin. I loved the dynamics between Mark and Anne, his lover, which were about sex, obviously, but so much more. A spiralling tension accompanies the loss of control as Mark finds himself in a situation even more complicated than he realises, from which distance and time will offer no escape. Running from the past or carrying the burden of its secrets has unavoidably become a back jacket cliché; luckily, the way it’s handled in this novel is not.

* If you’d like to hear me hold forth on this, here’s my essay on Writing about Love, recently republished on the Women Writers blog.

*POSTSCRIPT*

Next week, my guest is Juliet West, author of The Faithful, another of my Summer 2017 picks, on writing about social class.

.

Advertisements