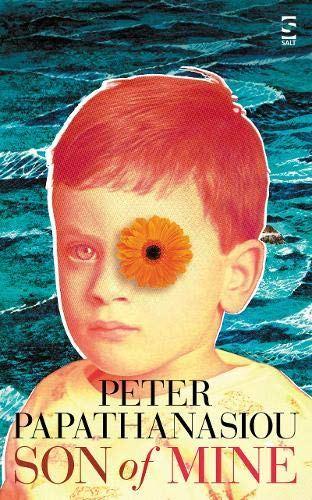

Five years ago, a friend asked if I’d be willing to meet up with a Greek-Australian writer who was new to London and the UK publishing scene and share a few tips. That writer is today’s Sofa guest Pete Papathanasiou, who joins me with the final post in my Summer Reads line-up just ahead of the UK release of his memoir Son of Mine, published by Salt on 15 July. (It’s already out in Australia and New Zealand under the title Little One.)

Five years ago, a friend asked if I’d be willing to meet up with a Greek-Australian writer who was new to London and the UK publishing scene and share a few tips. That writer is today’s Sofa guest Pete Papathanasiou, who joins me with the final post in my Summer Reads line-up just ahead of the UK release of his memoir Son of Mine, published by Salt on 15 July. (It’s already out in Australia and New Zealand under the title Little One.)

There’s a satisfyingly circular feeling to this: my tough experience the year Pete and I met was the catalyst to me co-founding the Resilience for Writers project with psychologist Voula Tsoflias (we’re looking forward to our Resilient Thinking workshop at the Mslexicon festival in Leeds this weekend), which has developed into one of the most rewarding strands of my writing career. And Pete is a prime illustration of resilience and perseverance, the subject he generously volunteered to write about today. I’m thrilled to welcome him to the Sofa and my review (with no claim to impartiality) follows his piece:

The publication of my debut book in mid 2019 comes after ten years of writing, many ups and downs, rejections and self-doubt. But as it turns out, there’s one final twist in the tale.

My book is a memoir about my international adoption as a baby. I discovered this truth in 1999 when I was 24, and first began writing about it in 2006 at a course in New York City. It was a short piece then, before it started to take shape as a book in 2008.

Fourteen drafts followed; dozens of hours spent sitting with my adoptive mum, recording her story, transcribing the notes, turning them into chapters. Having traveled to Greece in 2003 to meet my two biological brothers, I also added many of my own chapters. By 2011, I had a polished manuscript of 100,000 words with two narrators jumping back and forth in time.

Brimming with optimism, I approached literary agents but received only lukewarm interest. None offered contracts of representation. Feeling slightly disheartened, I put the manuscript in a bottom drawer. I was told that most people could write about their own lives but that that doesn’t make you a writer. The real test of a writer was whether you could write fiction.

So I began writing a novel in 2012. I got married in 2013; part of the honeymoon was spent at a writing course in Yorkshire. A year later, and with a view to promoting my writing, my wife and I moved to London permanently. I went to book launches, writing events, literary soirees, and enrolled in a Master of Arts at the University of London. I felt energised, connected, prolific. But then, two months later, my wife got pregnant. We packed up our one-bedroom flat in West Hampstead and returned to Australia.

A week later, I received three offers of representation for my novel from London literary agents. I’d made only 12 submissions. Following a series of intense late night phone calls, I signed with an agent. She sent my novel out to UK publishers but received no offers. The familiar black cloud of dejection returned. I was told to push it away by writing another novel.

From 2015 to 2017, I wrote a third manuscript, and finished my MA. In that time, I also became a father – twice – and lost my own father.

2018 shaped as a defining year. My agent was going to send out my second novel and I didn’t know if I would get a third chance. And with a growing family, it was also getting harder to write at home. After extensive edits and redrafts, my agent was finally satisfied with the shape of my novel. It was submitted to UK publishers in March 2018.

It was then that I reopened the file of my memoir. Slowly, I began working away at it again, editing old chapters and adding new ones. A lot of life had been lived since 2011. I finished in June and was pleased with the final product. I was keen to show it to my agent. But not long after, she informed me that my novel hadn’t been picked up by publishers and added that I might want to find a new agent.

I subsequently spent much of July and August in an existential hole. Picking myself up, I started submitting to new agents. More rejections followed. Casting my net wider, I submitted to publishers directly. Where I could, I entered my work into unpublished manuscript competitions. Even more rejections followed. But then, light emerged. I had an offer from a UK publisher, Salt, for my memoir, and two separate offers from Australian publishers before I signed with Allen & Unwin.

Meanwhile, my second novel was recognised by three unpublished manuscript programs. There had been hundreds of entries in each. And lastly, I also signed with a new literary agent. My wife and I went on a date night to toast my success. We’d already made travel plans for 2019: to be in the UK over summer for my book launch, and then stay with my brothers in Greece. ‘There’s just one problem,’ my wife said over dessert. ‘I’m, uh, pregnant.’

The baby is due a fortnight after my book is published in the UK. It’s wonderful news, albeit slightly inconvenient timing. This will be the unpublished chapter of my memoir. I’m thrilled to finally share my story with readers in 2019. I especially look forward to one day sharing it with my children too. In the meantime, I tell this story in the hope that it might provide inspiration to other emerging writers. Every debut author has a dogged story of struggle, doubt, rejection, and persistence behind their success. This is just my story. Keep at it. Keep going.

Congratulations to Pete (and his wife) on all counts and a very big thanks for speaking so openly about a journey which really captures the unavoidable peaks and troughs of the writing life. I’m proud to host this piece on a subject that matters to me and am sure Pete’s ability to hold onto his love of writing and belief in his story will indeed encourage other writers to keep at it.

Over the years, Pete wrote articles on his family history for publications around the world and given the emotional power of his life story and his gift for telling it, I felt unusually confident that this memoir would eventually be published. The result proves the advice he was given on ‘what makes a writer’ [see above] to be completely wrong; this is the work of someone who not only delivers beautiful prose but who writes with honesty, empathy and willingness to show vulnerability as well as courage. These are the elements which make his dramatic and unusual experiences so universal and poignant, going beyond individual circumstances to the challenge we all face to make sense of who we are. The human need for meaningful connection can be fulfilled in many ways, and is particularly well served by the written word.

Some unlikely thematic combinations add to the layers – I found Pete’s professional perspective as a geneticist interesting (and uncannily relevant), as was his engagement with his ancestral roots and family members in northern Greece. His adoptive parents’ experience as first generation immigrants to Australia lend the book a topical angle and Pete’s sensitive reflections on the different roles he plays in his own life make this a welcome antidote to the culture of toxic masculinity. A number of memoirs have done extremely well lately (I wrote about Tara Westover’s Educated here) – I think this has the potential to be one of them.

Advertisements