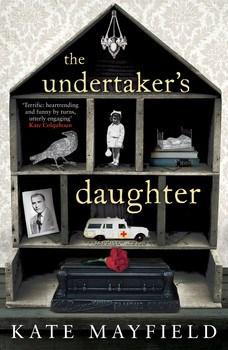

In this week’s holiday reading round-up I mentioned my new love of reading memoirs, but my enthusiasm for Kate Mayfield’s The Undertaker’s Daughter dates back even further, to the first time we met almost two years ago. When Kate told me her book was about growing up in a funeral home in rural Kentucky I couldn’t wait to read it and when I did it exceeded my expectations. I am delighted to welcome her as the first memoirist to appear on the Literary Sofa, sharing her experiences of writing about life and death. (My mini-review follows):

In this week’s holiday reading round-up I mentioned my new love of reading memoirs, but my enthusiasm for Kate Mayfield’s The Undertaker’s Daughter dates back even further, to the first time we met almost two years ago. When Kate told me her book was about growing up in a funeral home in rural Kentucky I couldn’t wait to read it and when I did it exceeded my expectations. I am delighted to welcome her as the first memoirist to appear on the Literary Sofa, sharing her experiences of writing about life and death. (My mini-review follows):

In Southern United States death culture there is a moment, a solemn, dreaded moment when a family comes together to view the embalmed body of their parent, sibling, or partner. It is often the moment when they see their relative dead for the first time. The deceased, usually fiercely loved, was alive just yesterday and now they are gone. The surviving family, as they are called, arrive at the funeral home weary from a sleepless night and are disoriented, weak and vulnerable. Often the grief and the awful truth haven’t even set in yet. They are uncomfortable with the newness and strangeness of death.

“The family’s here,” my father would say. This business of death had already begun, but now it’s reached the next stage, a public, casket-opening, door-opening stage.

Over and over again, day after day, the rituals and emotions of death drifted in the air of my childhood home. How could I, how did I write about that?

I began by simply trying to remember each room in the funeral home, the details of which emerged slowly and then, suddenly, rushed through in an overwhelming surge. Soon those rooms began to fill with the people of the town, both dead and alive. Then I climbed the steps to the first floor where my family moved through the rooms, mostly in silence – the state of being in which we were often required to live. I wrote what I saw and heard. I stewed.

Why did I remember certain funerals and not others? I recalled snippets of conversations, ghost-like. ‘Mrs. Thompson died.’ ‘We’re having chilli for supper.’ I spent an enormous amount of time watching and listening.

When I wrote about death I thought of life, the life around me, the lives of the deceased and their families. When I wrote about life, I was aware that another death was just around the corner.

People have asked me if I found the process of writing a memoir cathartic. No, I didn’t, not in the truest sense of the word; it wasn’t purgative, or exorcising. That’s not to say that I didn’t experience all of the emotions that such an endeavour would naturally evoke.

In fact, what I needed most was distance, not a purge. Not until I changed the names of most of the people in the book was I able to gain any objectivity. I found if I also changed place names, I was able to imagine the geography in a less intellectual, more sensual way.

There were all sorts of traps and mines. Further down the road in subsequent drafts the most daunting of these were decisions about what to leave in, what to cut. There was a search for what was missing, and surprisingly, I was missing. My editor was very good – and persistent – at drawing me out. I was a reluctant character.

There was a great deal more research to do than I had originally planned. That’s probably an understatement. I sourced my father’s medical records from WWII. I still stumble over a box that contains over a thousand pages of the court case, unsure as I am of its final resting place. The mother of a main character (are they still “characters” if it’s a memoir? I don’t know) kept a 19th century scrapbook. It is littered with clippings, death notices, mourning stationery – fascinating on their own – but also the material aided my understanding of the character’s world as a child before I met her, which was when she was much older. I had no idea any of these archival materials existed before I began writing the book.

I once attended a panel of memoirists at a book festival in Los Angeles when I was just beginning to settle down to think about my own. Each author agreed that a writer shouldn’t worry about what his or her family members might think or do. At first I thought that was quite a harsh view, but then I quickly understood what they meant. You’re either going to grab the story by the collar and shake it until it drops out on the page, or you’re going to skirt around it like a prissy schoolgirl; if the latter, you have no business writing a memoir.

In any sort of writing project, fiction or non-fiction, it’s vital to go deeper than you ever thought you could. I reached a ledge where I thought, no, I cannot jump one more time. But I did, and you do, you just do. It isn’t easy, but then writing isn’t easy.

A writer can be fair and sensitive, handle the hot spots delicately, and still convey hard truths. Readers are smart and sophisticated; they get it.

Thank you for having me on your sofa, Isabel!

And thank you, Kate, for being here – this piece is not only great inspiration for anyone working on a memoir, but as you say, some of it applies to fiction too.

It’s always a slightly worrying prospect to read a book when you know the author but I can honestly say that The Undertaker’s Daughter was an absolute pleasure from beginning to end. Kate’s unusual background undoubtedly provides her with great material, but it takes some skill to transform that into a full-length book which has the all the authenticity and honesty of a memoir but works so well as a narrative, with such a strong storyline, that it also reads like a first-rate, first-person novel. Kate captures the atmosphere, voices and culture of her Kentucky homeland with transporting vividness – to read this is to find yourself there back when… The intriguingly macabre world of the funeral home is tempered with southern warmth and gentility and a memorable cast of characters, though darkness is never far beneath the surface. I am at a loss to think how it could have been done better. If you liked The Help, you’re going to love this!

*POSTSCRIPT*

I am very pleased that bestselling Canadian author Emily St John Mandel will be joining me next week to talk about her latest release, dystopian novel Station Eleven.