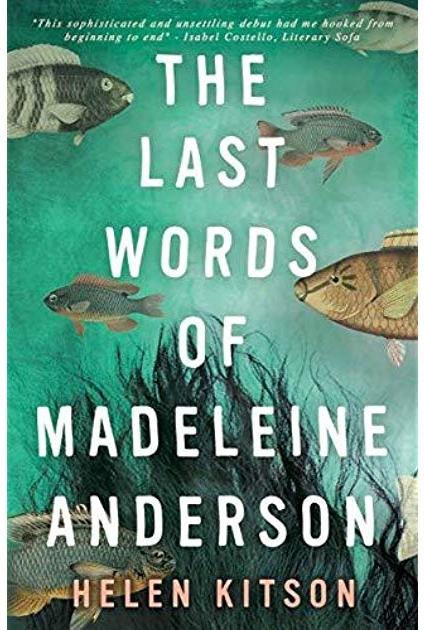

Today the coverage of my Sofa Spotlight titles continues following my trip to Senegal and I’m delighted to welcome debut novelist and self-described ‘ex-poet’ Helen Kitson, whose novel The Last Words of Madeleine Anderson is amongst the first releases from small independent press Louise Walters Books. Louise has appeared on the Sofa with each of her own three novels and given her excellent taste and judgement, it was only a matter of time before one of her authors joined me here.

Today the coverage of my Sofa Spotlight titles continues following my trip to Senegal and I’m delighted to welcome debut novelist and self-described ‘ex-poet’ Helen Kitson, whose novel The Last Words of Madeleine Anderson is amongst the first releases from small independent press Louise Walters Books. Louise has appeared on the Sofa with each of her own three novels and given her excellent taste and judgement, it was only a matter of time before one of her authors joined me here.

By coincidence, the current crop of Spotlight titles has resulted in a fantastic Writing about… mini-series thanks to guest authors Catherine Simpson on mental health, Isabel Rogers on music, and next week Eleanor Anstruther on turning a family story into fiction. Today’s guest Helen has bravely tackled something which is regularly attempted, inherently risky and sometimes viewed with suspicion: writing about writers. To me her novel proves how satisfying this can be when it’s done well, and you can find out more in my review following her piece:

I began writing my novel because a simple question wouldn’t leave me alone. Assuming a writer had enjoyed a decent writing career, had been published, why would they suddenly stop? I pictured someone who had no major commitments, nothing tangible to stop them writing. Writer’s block seemed too simplistic and too potentially navel-gazing to explore. I wanted something else, a bigger reason, something that didn’t so much block as put up steel barricades.

It’s a question that bothered me because it’s something that pricks me every time I see any reference to my published collections of poetry. From the age of around seventeen until I was in my thirties, I wrote and published poetry. And then I stopped. My last collection was published in 2010 and included a long sequence of poems I wrote in response to research I’d undertaken into my family tree. Although the poems aren’t personal per se, writing them felt like a way of coming to terms with my own past and probably had much to do with my father’s death in 2008. On the rare occasions since then when I’ve attempted to write poetry, the results have felt stale, mere rehashing of themes I’ve already shaken out. There simply wasn’t any gas left in the tank. When I re-read my published poems it’s like reading the work of someone else. I almost feel like a fraud in claiming them as my own.

This, perhaps, is why the ‘writer who doesn’t write’ was a theme that wouldn’t let me go. In no sense autobiographical, many of Gabrielle’s experiences are drawn from my own. Those first tentative steps. The first time you show your work to someone else. The first acceptance from a literary magazine. The rejections. The knowledge that you’ll never be as good as you’d like to be. At the same time, I didn’t want to dwell too much on literary angst or to resort to clichés or tropes (the writer starving in a garret; the depressive genius; the word-blocked boozer who treats his or her nearest and dearest appallingly).

Gabrielle’s predicament is that she published one brilliant novel in her twenties and then, apparently, wrote nothing for the next twenty years. This invites suspicion in the people who know her. If you can write one book, why not another? She makes excuses, as I do when people ask me if I still write poetry. The suspicion is that you’re not trying hard enough. That it will come back to you ‘eventually’. We’re tough on writers. We expect them to keep going despite everything unless there’s a very good reason why they shouldn’t. If Gabrielle had children or a career, she might have been left alone to enjoy her status as one-hit wonder. It’s more complicated than that, but isn’t it always?

At the back of my mind when I was writing the book was Angelica Deverell, the title character in Elizabeth Taylor’s wonderful novel Angel, first published in 1957. If Gabrielle suffers from ‘literary constipation’, Angel has the opposite problem. She churns out novels she thinks are brilliant, unaware that her publisher adores them for their unintentional hilarity. Angel has no sense of humor and little self-awareness. She is, in short, a monster, but such is Taylor’s skill that we care what happens to her. Although Taylor’s fabulous novel is very different from mine, Gabrielle is in some ways the anti-Angel. She has too much self-awareness and spends far too much of her time dwelling on the past. Dreadful though Angel is, one can hardly fault her for her having an extraordinary work ethic. The problem is that she is never happy, even when she seems to have everything she could possibly want in material terms.

Angel’s life is emotionally and intellectually impoverished, and in many ways this is also true of Gabrielle. I suspect many readers will blame her for this and find her irritating. Her past is more meaningful to her than the present or the future, and I’m sympathetic to this aspect of her. My final (and it will more than likely be the final) collection of poetry dealt squarely with the past. Once that was done, I drew a line under writing poetry. It was done. Over. Even so, I’ve had people look at me oddly when I describe myself as an ‘ex poet’. There’s something suspect about the statement, yet a statement of fact, and one that doesn’t make me sad. Writers need to care about what they write and they need to have something to say. This, I think, feeds into why I wanted to write a novel about a writer. The stories we live are as important as the stories we write; and sometimes (indirectly or otherwise) they are one and the same thing.

Thank you to Helen for this revealing piece – I’m sure many readers and writers will be as fascinated as I was to discover what motivated her debut novel.

The mysteries of storytelling reveal their many layers in this sophisticated and unsettling debut which had me hooked from beginning to end. Helen Kitson’s poetic sensibility is still evident in prose which impresses with its unaffected elegance, precision and shots of dark wit; a great example of ‘accessible literary fiction’, wearing its complex ideas lightly. This is a story in which nothing can be taken at face value, starting with first person narrator Gabrielle, whose dull and unfulfilled life make her easy to underrate. Despite episodes of infuriating passivity and almost implausible naïveté – including the circumstances in which young fan Simon crashes into her life – she is a thoughtful and intelligent woman and a masterclass in subtle characterization. Against the odds, I ended up empathising with her and several poignant moments have stayed with me for months. However bizarre and unlikely the ménage between Gabrielle and Simon, it led to great conversations (the literary references – including French ones – are a treat) and some genuinely excruciating dynamics. With a sense of menace simmering beneath an unassuming exterior (no reflection on the gorgeous cover!), this book really got under my skin and kept pulling me back despite my efforts to ration the remaining chapters. Consider that a warning and a strong recommendation to readers, and writers in particular – the only reason I didn’t turn my critical radar off was because I had so much to learn.

*POSTSCRIPT*

As mentioned above, Eleanor Anstruther will be joining me next week to talk about Fictionalising a Family Story in her debut A Perfect Explanation. I will also be posting a round-up of my recent holiday reading.

Advertisements