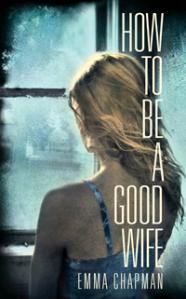

Emma Chapman’s debut novel How To Be A Good Wife was released last week after months of mounting anticipation amongst would-be readers. I had the good fortune to read a review copy in the autumn and to meet Emma and other up-and-coming Picador authors shortly afterwards, and I was so impressed with her debut that it made my Fiction Hot Picks for 2013. I’m delighted to welcome Emma to the Literary Sofa as my first guest of 2013 to talk about the unnamed Scandinavian setting of the story, an aspect I found particularly intriguing… My mini-review follows.

Emma Chapman’s debut novel How To Be A Good Wife was released last week after months of mounting anticipation amongst would-be readers. I had the good fortune to read a review copy in the autumn and to meet Emma and other up-and-coming Picador authors shortly afterwards, and I was so impressed with her debut that it made my Fiction Hot Picks for 2013. I’m delighted to welcome Emma to the Literary Sofa as my first guest of 2013 to talk about the unnamed Scandinavian setting of the story, an aspect I found particularly intriguing… My mini-review follows.

How To Be A Good Wife is set in an eerie landscape: vast mountains, deep fjords, with nights that come too fast and darkness that lingers. The action takes place in a house in a remote farming area. This sense of isolation, of a natural world out of the protagonist’s control, is an important aspect of the book.

After university, I traveled extensively in Scandinavia. I left with a backpack and a tent, and camped wherever I had reached by nightfall. On the edge of dark lakes, beneath looming mountains, I washed in rivers and streams. It was thrilling: the vastness of the environment, the lack of people, and the sense of freedom. Everyone seemed kind and friendly: the locals going out of their way to make me feel welcome.

I remember one particular valley, which has returned to me many times since. There was the low curve of the valley, rising to sloping green hills, and beyond them, higher and darker mountains that seemed to watch over everything. The houses were carefully tended to: neatly painted, with blooming window boxes and dusted windowsills. I took a walk with a friend into the hills, and was amazed at how the landscape changed as we climbed higher: the houses becoming smaller and more toy-like every time I turned to look over my shoulder. The people who lived such an idyllic rural existence intrigued me.

That night, we camped on the shore of a fjord overlooking the valley. We set up for the night, putting up the tent and collecting wood for the fire. As we were trying to get the flames to catch, a boat appeared across the fjord, moving slowly towards us. The man standing on board called out to us, angrily shouting that we couldn’t stay there, or light our fire. This was his land, his shore. There is a rule in Scandinavia that you can camp anywhere as long as you are not within 200m of anyone’s property. Frightened, we packed up our things and moved on, worried the man would return. In that moment, the landscape seemed to bear down on us: the wind picked up and the rain began to fall as the day faded, as if we had stepped out of line and were being punished. An undercurrent of something began to reveal itself. I knew then that I wanted to write about this place of natural extremes, but I hadn’t found my story yet.

On a train months later, Marta’s voice came to me, and I wrote the first scene of the book. Marta is smoking in her kitchen, though she never remembers having done so before. It is a small act of rebellion: one she herself doesn’t understand. I knew the house was surrounded by darkness, and that the landscape she inhabited was one similar to the remote villages I had visited. She was damaged, and control was important to her: the natural world that refuses to obey becomes a catalyst in her unraveling.

As the story grew, and I researched further into Marta’s situation and her mental state, the setting seemed to take on a life of its own. It was important in building the suspense of the early chapters: in suggesting that despite Marta’s mundane domestic life, perhaps all is not what it seems. As the book progresses, and Marta begins to see things or perhaps to remember, the natural world around her refuses to make things easy for her. When she longs for light at the window to make everything clear again, it refuses to come; when her world starts to slip from her grasp, snow falls and covers the familiar. The landscape became both more specific to Marta’s unique situation and more general in its refusal to alter to aid one individual.

Originally, I researched town names and suitable locations, even returning to Scandinavia to search out the right place to set the book. I gave the town a real name, and referred local points of reference. But as the story of Marta and Hector’s marriage became more complicated, I realized I wanted the setting to be more universal, like the trials of marriage. I removed the town name, and the other references to specific local foods. I wanted the polarizing extremes of the natural environment to speak for themselves, to almost become a fairy-tale type motif within the book: dark forests, crashing rivers, sudden darkness. I worked extensively on fairy tales while at university, and was particularly fascinated by how the landscape adds drama and mimics the mood of the protagonists.

When I started the book in 2008, the trend for all things Scandinavian hadn’t yet taken off. I did wonder while I was working and reworking the novel whether books like The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo, and television series such as Wallander and The Killing, were saturating the market. I only knew I had chosen the setting that felt right for my book, and I couldn’t alter or change it due to the current trends in popular culture.

How To Be A Good Wife tells the story of a particular marriage, but it also explores overarching ideas about matrimony and the limitations of a woman’s role. The setting seems to complement both the sense of menace and normality that breathes through the book. It helps to raise questions as to whether everything is as it seems. It highlights Marta’s need for control by denying it, as the world around her looks on blindly while simultaneously seeming to converge at the moment of her disintegration.

Thanks to Emma for this fascinating insight into her very significant choice of setting. It’s made me see a distinction between an unnamed location and a completely fictitious one (something I’m not usually keen on). Do you have a view on this or any thoughts on the many Scandinavian influences in contemporary fiction?

This may surprise you, but in one way I dread starting a new book and the effort it takes to enter a different world. However, if I’m impressed by the writing itself in the first few pages, I start to relax, regardless of whether the ‘hook’ is strong, because I already have faith in the author’s ability. When I began How To Be A Good Wife, I was instantly taken with Marta’s voice, pulled into her head and what it was like to be her. Emma Chapman’s writing is my absolute favorite kind: spare, tense and intensely evocative of landscapes both physical and internal. It has a searing, almost forensic quality. My only reservation concerns the title, which I think sounds a bit light or whimsical; luckily the novel is nothing of the kind. It is unsettling, dark and meaningful, with insights into marriage, motherhood and aging that are all the more extraordinary coming from an author who is only 27. (I’m still desperate to know the place Emma had in mind for the setting though. I wonder if she’ll tell me…?)

*POSTSCRIPT*

Next week – a travel report on our amazing Christmas trip to South Africa, with lots of pictures taken with the new camera. I’m already working on a short story set there.