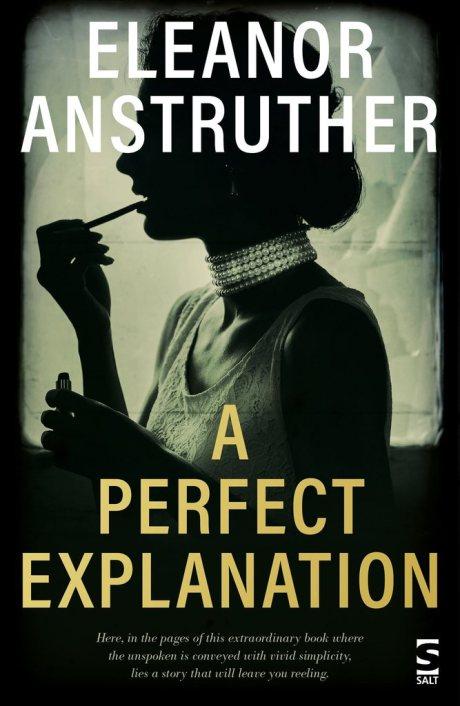

My First Sofa Spotlight of 2019 celebrated nine fantastic new releases and this is the penultimate post from the authors. This is one of the strongest ‘seasons’ I’ve been fortunate to host, and it’s a pleasure to be joined today by Eleanor Anstruther, author of A Perfect Explanation. I met Ellie very briefly at her launch a couple of weeks ago, where the support from a huge crowd of family, friends and book people was palpable. I suspect that is partly because this book is so personal and required exceptional bravery and perseverance, being closely based on events in her family which prove that real life can be as dramatic as fiction. Ellie explains how she brought the two together in her debut novel, and my review follows:

My First Sofa Spotlight of 2019 celebrated nine fantastic new releases and this is the penultimate post from the authors. This is one of the strongest ‘seasons’ I’ve been fortunate to host, and it’s a pleasure to be joined today by Eleanor Anstruther, author of A Perfect Explanation. I met Ellie very briefly at her launch a couple of weeks ago, where the support from a huge crowd of family, friends and book people was palpable. I suspect that is partly because this book is so personal and required exceptional bravery and perseverance, being closely based on events in her family which prove that real life can be as dramatic as fiction. Ellie explains how she brought the two together in her debut novel, and my review follows:

You had one effort and one effort only; to provide this family with an heir. So says Sybil, to her daughter Enid (my grandmother) in the opulent surrounds of their Scottish home, where the family have gathered for the summer. In that one, terrible phrase Enid’s mother – old and desperate, encased in Victorian satin and centuries of habit – lays bare the bones of her relationship to her daughter, her family, and society itself. It is these bonds, or lack of them, that lie at the heart of A Perfect Explanation.

I uncovered the bones, the what’s it about, from one set of facts known widely within the family. My father was sold for £500 by his mother to his aunt. Who were the people who did this? How could they have let it happen? My ancestors were people of great privilege. Descended from the dukes of Argyll, their relationship to society was clear; they knew the rules and accepted their part. They had a name to uphold, and a fortune to pass on. But what of their relationships to each other? Where financially they lacked for nothing, emotionally, they were impoverished. They didn’t like each other. They put money, name and society first.

If you’ve been taught that these are the things that matter, that securing inheritance and upholding a name will give you security, then in a sense, it’s hard to blame them. They were of their time and class, knew no different, and knew no better. They did their best, and failed to care for each other. It is something, to accept this about one’s family, to know that they treated each other badly. It’s hard to not take sides, disassociate from the worst of them and paint others as having done no wrong, but it wouldn’t be fair, and fairness is what they lacked.

Writing a family story is all about relationships; the unpicking and gathering up, the sorting of the real from the fictional, and ultimately, the writer’s relationship to the story itself. Where Sybil was bound, as matriarch, by her duty to the family estates, I, her great granddaughter, was bound as writer by my duty to the narrative.

Narrative demands a beginning, a middle and an end. Real life isn’t like that; the events of our lives are an endless interweaving of cause and effect and family stories are no different. They seep from one scene to another, trail off in different directions, are at the mercy of hearsay, circumstance, context and chance, and can be interpreted in myriad ways. My great grandmother wasn’t the only voice in my head, wanting to tell her side. Every one of the characters – my relations – had a version they wanted told, and each a good reason to be the center of the story. With multiple viewpoints, it became impossible to choose who was right and as I tried to make sense of it I realised, through sheer frustration, that a certain detachment was necessary. The question of who is writing the story, became paramount and affected every technical decision made after.

I had to stop being a great granddaughter, granddaughter, daughter and niece, and start being a writer. My duty, unlike Sybil’s, was to tell a story without prejudice, and it was imperative that my relationship to it be just that. Duty to anything comes with a price; there will be parts forgotten, blurred or skipped over, and even though the end result will waiver sometimes from telling every aspect, what is produced is a book that promises to do what books should promise – to tell, without bias, a story, and leave it to the reader to decide how they feel.

How I feel is relieved. It took a decade to learn how to write this book. I tore everything up and started again multiple times. I wrote versions from every viewpoint; first person and third, changed my mind over what it was about, tried fictional names and real, changed tense from present to past, and played with it as biography and memoir, until I arrived at this; a fictional account of a true story that uses real names and creates through imagined scenes and conversations, an explanation of how this family moved from united to broken. Writing it has changed my relationships to everyone involved; even though I knew none but my father, my sense of them, and how I relate to them, has altered. I no longer think about who was to blame, I no longer point the finger. They were people first, wealthy and entitled, second. If relationships are to be mended, even dead ones, then a great granddaughter must start somewhere, and a writer must start at the beginning.

Thank you to Eleanor for this fascinating insight into her challenging but rewarding personal and literary endeavour.

No matter how long you’ve been doing it, some books are difficult to review and this is one of them for me. I recommend A Perfect Explanation without hesitation to anyone with an interest in complex family relationships and/or social history and yet it’s a book which I found deeply tragic and often upsetting to read, particularly knowing it’s based on real events. Perhaps the interesting thing to explore is how these reactions came to co-exist. As is evident from today’s piece, the author achieved an admirable degree of detachment in her examination of behavior which many people would consider shocking and reprehensible; it’s a compelling story which will test readers’ empathy and capacity to withhold judgement, but one which is compassionate in intent, inviting reflection long after the last page. This would make it an excellent book to discuss and I feel I understand it better at a distance.

Many of the circumstances – especially those of Enid, but the other women’s too – are a direct product of their time and social environment and would be seen very differently now. At a time when there is rightly a movement towards greater diversity in publishing, it’s important to guard against simplistic polarization and this is a far-sighted publishing decision by Salt; privilege in all its forms has long been over-represented in fiction but it’s never the case that everything has been said, on any subject. This is as much a story of emotional deprivation as of entitlement or riches, and one which underlines that no group has a monopoly on humanity, fragility or fallibility – these are universal and so is this devastating and exquisitely written novel; we are all just people, in the end.

*POSTSCRIPT*

The final post in this series, in a few weeks’ time, will be the first Writers on Location of the year (it doesn’t usually take this long): Lisa Blower on the Staffordshire Potteries, setting of her collection It’s gone dark over Bill’s Mother’s, a triumph of regional and working-class storytelling. There will be other stuff between now and then!

Advertisements