There was a really enthusiastic response to my First Sofa Spotlight of 2019 a couple of weeks ago – many thanks to everyone who got in touch, shared it on social media and entered my one day competition on Twitter. I hope the winners and the rest of you are enjoying the books you chose!

There was a really enthusiastic response to my First Sofa Spotlight of 2019 a couple of weeks ago – many thanks to everyone who got in touch, shared it on social media and entered my one day competition on Twitter. I hope the winners and the rest of you are enjoying the books you chose!

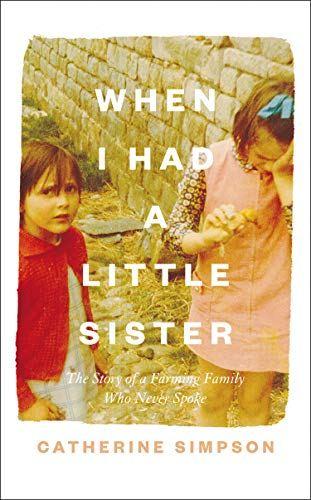

Today it’s my pleasure to welcome the first in a fabulous line-up of guest authors featured in the Spotlight. Catherine Simpson has visited the Literary Sofa before, on release of her debut novel Truestory, which was inspired by her experience of motherhood. When I Had a Little Sister really is a true story, a family memoir prompted by the suicide of Catherine’s sister, Tricia.

I invited Catherine back because I believe the gradual de-stigmatisation and increasing openness about mental health issues is both positive and necessary – according to charity MIND, ‘approximately 1 in 4 people in the UK will experience a mental health problem each year’ and ‘the number of people who self-harm or have suicidal thoughts is increasing’. Having grown up in a family where mental health issues were seen as shameful and ignored at great personal cost, I have spoken about recently seeking help through therapy – which I finally did because both friends and strangers talking about it made it feel like a natural and positive thing to do. Books like this memoir make a vital contribution to this change, and as you will see from my review at the end, it resonated strongly with me for all kinds of reasons.

My little sister, Tricia, died by suicide in 2013 aged 46. At the time another writer said to me: ‘You’ll write about this one day,’ and I shook my head. Where would I begin? The subject was too big and overwhelming. The idea of writing about such a personal and heart-breaking subject was too frightening.

But two-and-a-half years down the line I got the urge to explore Tricia’s diaries – she had left behind a pile of notebooks and diaries dating from the age of 14 until she died. I retrieved them from my big sister’s attic and took them with me on a writing retreat to Hawthornden Castle, in the Scottish Lowlands.

I had planned to work on a draft novel at Hawthornden but did not receive the feedback I needed in time. So instead my stay in the castle was spent reading Tricia’s diaries and beginning work on a memoir called When I Had a Little Sister. This book would explore our family history and try to work out why Tricia’s story ended as it did. My intention was to understand Tricia and the events of her life as deeply as I could.

As I immersed myself in the diaries and then began to put pen to paper, I realised it was a relief to explore the subject of my sister’s experience with bi-polar disorder and my own on-off experiences with depression.

Silence is disabling and shaming, and expressing some of our experiences felt empowering. This was in stark contrast to the way I had been raised, as indicated in the book’s subtitle The Story of a Farming Family that Never Spoke – a state of affairs probably not uncommon in families of the 1960s and 70s.

Silence perpetuates the stigma around mental illness that can make us believe we are blameworthy or somehow of lesser value if we have poor mental health. For me it was time to break that silence.

I am far from the only one to be writing about mental ill health. There are many accounts of mental health issues out there ranging from best-seller Matt Haig’s Reasons to Stay Alive and Notes on a Nervous Planet, to individual testimonies on websites like The Mighty.

And each story is unique and important and is worth telling.

I have used my personal life in my writing before. I used the experience of raising my autistic daughter as inspiration for my novel Truestory – but that inspiration was mixed with a cast of invented characters and a fictitious plot. This time it was completely different. I was writing about private matters that involved real people and real events in real places. I did lose sleep about this and at the bottom of it all was the question: What would Tricia think?

I decided to write it as honestly as I could asking myself: is this fair? Is this the truth as far as I understand it? Is this relevant? If the answer was yes to all three then the information was included. Some passages in the book are upsetting, including descriptions of locked wards and deep depression and loneliness. Others are humorous.

I wanted to write about Tricia as a rounded person, showing that her mental illness was only part of who she was. She was a horse-woman, a piano-player, a great story-teller who loved music and animals, travel and cigarettes. Mental ill-health seemed to be an ever more powerful part of her life as it progressed, but it was still only part.

I wanted to create a loving tribute to my little sister.

But I also really wanted the story, once told, to help other people with mental health issues and their families. I hoped it would give people strength, that it would help to cut any sense of isolation and to create understanding. I hoped it would encourage other people to talk before it was too late.

Just before the book went to print I read an article saying the phrase ‘committed suicide’ should not be used as it suggests criminality and blame and perpetuates stigma, when in fact suicide was decriminalised in the UK in 1961. I checked through the manuscript and found I had used the phrase ‘committed suicide’ twice. I immediately changed them to the suggested ‘died by suicide’.

Tricia was very creative and loved writing and painting and I decided to include in the book some direct quotes of hers and a copy of her acrylic self-portrait – so that even though she is not here to see them her words and art are now published.

I think she would approve.

Many thanks to Catherine for this important and heartfelt piece which I hope will reach a wide audience. I’m sure Tricia would approve.

Whilst this is obviously a tragic story and some parts are upsetting to read, it is far from a depressing book. This memoir only exists because of Tricia’s illness and suicide, but this is only one aspect, and due to the seamless structure and balance it reappears at intervals rather than dominating the narrative in tone or content. Similarly, the author’s writing style, which I enjoyed in her debut Truestory, lends itself to the task; it has a beautiful clarity and restraint which conveys emotion without becoming overwrought.

For me, a good memoir is one in which, however familiar or extraordinary the lives depicted, the reader finds some reflection of their own experience along with some kind of revelation. Whether or not this happens often comes down to the courage and honesty of the author. This book doesn’t shy away from the pain severe mental illness inflicts not only on the individual, but on those who love them – and yet they are all just people like anyone else. There is more to them than this, and that comes across vividly here.

This picture of a way of life, on a Lancashire farm, will appeal to readers who welcome more regional and social diversity in written voices – I loved the glimpses of older relatives’ lives and the photos included throughout. But at heart, this is the story of an ‘ordinary’ family with complicated dynamics that make it universal as well as insightful – in that sense it could be anywhere. I found this a very powerful and moving read but could especially relate to Catherine’s distant and painful relationship with her mother – amongst the many flashes of wisdom, I felt a stab of recognition but was also consoled by her observation about the particular conflict of mourning a difficult relationship – I had never seen this articulated. Many readers will experience their own moments of emotional connection, and many readers is precisely what this book deserves.

*POSTSCRIPT*

As it’s on topic, I’m taking the opportunity to recommend a very generous and enlightening series of blog posts by my friend and workshop co-presenter, psychologist Voula Tsoflias, on Resilient Bereavement. Voula documents her year of ‘re-setting her brain’ following the sudden death of her younger brother.

Next week’s guest author is my great friend Isabel Rogers, poet, wit, and newly published novelist, who joins me with a post on Writing about Music, an essential requirement in her debut Life, Death and Cellos, the first of The Stockwell Park Orchestra Series.

Advertisements