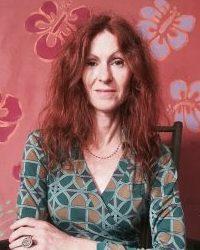

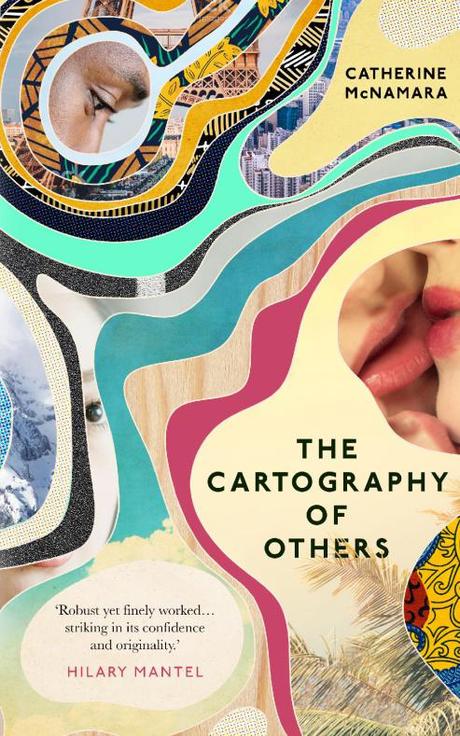

Back to my Summer Reads and I’m declaring this week’s post a Special Edition, partly because it’s a change from the normal format but mostly because I am so thrilled to be hosting the talented and lovely Catherine McNamara, whose second solo short story collection The Cartography of Others was recently crowdfunded by many and published by Unbound. Catherine and I met years ago at one of the first Word Factory salons in London, where her work made an instant and lasting impression on me. Since then we have bonded over a love of Paris and a shared interest in sex and desire, central themes of our work. In addition, we have both been strongly influenced by cultures beyond our similar backgrounds on opposite sides of the globe; for me, that influence is France; Catherine has many, as you’re about to find out. Since I don’t review short fiction as such (you would not thank me for ruining her wonderful stories), I will follow with a personal response to Catherine’s piece, and to Cartography.

Back to my Summer Reads and I’m declaring this week’s post a Special Edition, partly because it’s a change from the normal format but mostly because I am so thrilled to be hosting the talented and lovely Catherine McNamara, whose second solo short story collection The Cartography of Others was recently crowdfunded by many and published by Unbound. Catherine and I met years ago at one of the first Word Factory salons in London, where her work made an instant and lasting impression on me. Since then we have bonded over a love of Paris and a shared interest in sex and desire, central themes of our work. In addition, we have both been strongly influenced by cultures beyond our similar backgrounds on opposite sides of the globe; for me, that influence is France; Catherine has many, as you’re about to find out. Since I don’t review short fiction as such (you would not thank me for ruining her wonderful stories), I will follow with a personal response to Catherine’s piece, and to Cartography.

I am always unsettled when readers comment upon the sensuality of my stories. For an instant I feel exposed, oversexed. And yet, how can one not write of this central theme in our lives? Without using sex as a titillating tool, I find I am compelled to write of the unravelling between men and women, to explore the realm of story through shimmery, elusive desire.

In writing The Cartography of Others, I experienced many different springboards for that leap into each story. The discomfort of an uneven erotic coupling; the gait of a man as he walks… where? Or, you burrow into the mind of a cook on a tour boat in the Mediterranean, whose boyfriend is drifting away from her? Yes! You decide to chart the space between them, narrowing and fluxing like the sea itself. You bring in an opera singer tourist who has lost her voice… To be honest, I love the act of writing. I love the void, the invention, the cadences, the adrenalin. I almost think it is sexy! Perhaps that is why I allow sensuality to unfurl, as men and women glance at each other, bathed by the other’s regard.

Our desires are primal, brought to us through the history of our cells, the impact of families and rebellion and harbouring – a myriad of layers that might suddenly be shed upon one person, the beloved. For love is at the heart of our lives. Yet our desires are so often flawed, rebuffed or finite, they condition us, they are our story. These are the stories I try to convey.

I have lived in many places. Very young, I left Sydney for Europe. I read Christina Stead’s For Love Alone, Shirley Hazzard’s The Transit of Venus, masterful authors who left Australia’s shores to write. I was greatly influenced by their devotion to language, to love, by the humanity of their gaze. For three years I lived in Paris above a sweatshop in the now-trendy 11th arrondissement. In this rough neighbourhood I worked hard to understand the language, to cope with the unfamiliar cold and initial loneliness. I was broken down, my comforts removed, and I examined my womanhood with resolve. It was here that I began to grow into myself.

There are certain cities or environments that tap into our psyches and allow for an acceleration of our personal development. Looking back, we see our younger selves propelled towards objectives that then seemed intangible. In Paris I wrote a lot of rubbish, but I gathered stories. I observed endlessly, I came across the intellectual frankness of French lovers, I read Anaïs Nin, reread Simone de Beauvoir. When I go back to Paris, I see a young Catherine walking the streets with her oversized leather jacket and skinny pants, trying to look as though she owned the place. It is a tender thought: I see her searching for the honesty and fearlessness that would inform her later work.

I also lived in East and West Africa for 12 years. Again, I learned about identity loss and the lack of footholds in different cultures. I traveled widely, changed lives. What I did experience was the dizzying vividness of reality, the currency of African modernity, the throb of music, the injustice of colonization weighed against the riches of history, the heart-breaking tragedies of the everyday. And within this, desire, love, proximity, adoration. The many stories in Cartography that are set in West Africa reflect how unshielded we can become, in love. From the European man besotted by a local man he must risk the law to see, to the puzzled niece brought to Ghana by her infertile aunt for an egg transplant.

Writing about sex is risky. Every year, we squirm when we read the contenders for the Bad Sex Award, often highlighting a clumsy male gaze. Bad sex scenes jar. The reader lingers over this act we share, especially if shabbily conveyed. Instead, we wish to read about the candour of sex, the interior sea of desire that consumes or contracts. The erotic sentiment painted suggestively, more than graphic sensations of thrusting or poor metaphors.

I confess I write about sex with the same intensity as I do about anything else. It should not be a highlight, but a tonal element of the texture of the story, as essential as consistency in voice or graceful paragraphs. It should not cry for attention, but should warm the reader, intimately, privately. And as I grow older I can’t see my stories – or my life – becoming sedate: I will continue to map out stories that do not shy from desire.

Firstly I’d like to thank Catherine for her visit and for this personal and engaging piece. Writing about sex and sexuality in a frank and realistic way often earns the observation that it is ‘grown up’. I’m guessing most authors take that as a compliment – I certainly do – but it’s interesting to reflect on the climate in which this needs saying. Aren’t we adults? I’ve long been bemused and frustrated by the embarrassment, shame and immaturity which so often surround ‘scenes of a sexual nature’ in the anglophone literary world. (You can read me railing against the Bad Sex Award here.) We are surrounded by sex in everyday life: to excite, to entertain, to sell us things and make us feel good (or bad). Female sexuality is exploited and misrepresented for all kinds of purposes, its complex realities not so acceptable. Fiction offers readers and writers an unmatchable opportunity to explore the intimate and unspoken aspects of human experience from the inside; like Catherine, I believe sex and desire are too big a part of who we are and how we behave not to seize that opportunity.

Those of us who do know what we are getting into. Of course it’s risky, and exposing, but these are factors every writer has to weigh up to some extent; what we choose to write and the way we go about it says a lot about us. Men’s interest in sex is taken as a given, but honest and realistic expressions of sexuality by and concerning women are still judged differently, whether on the page or in everyday life. All the more reason to do it. The constant emphasis on the difficulty of writing sex has become part of the problem – whatever the ingredients of good sex in fiction (opinions vary), self-consciousness is not one of them!

Sex and desire are a significant dimension in The Cartography of Others, but one of many, including identity, loss, betrayal, cultural dislocation and especially, place. I like the depiction of sexuality as a natural and organic part of life (as in much of French fiction and culture), embedded in character, not an attention-seeking big deal. It is direct, sometimes explicit, often erotic but at heart Catherine treats sex and desire like any other aspect of the story, with prose which combines poetic sensibility and sensuality with exquisite clarity. These stories could not have been written by anyone else (which should be true of all fiction, but sadly isn’t), many demonstrating a pleasing disregard for the ‘rules’ of the short form in that they are not necessarily about a single situation or dilemma and some are dense with back story.

What struck me most is the author’s ability to plunge the reader into a complex set-up (there are no predictable premises here), some with many characters, and make it work. I can only compare it to being three chapters into an utterly gripping novel – and this within the space of a few lines. My personal favorite was Hôtel de Californie, the sensual and moving gay love story mentioned above. For me this collection was more keeper than casual encounter, an inspiration and a reminder of the power of words to seduce.

Related posts:

Sex Scenes in Fiction

Special Edition: Guest Author – Isabel Losada: Sex – Let’s be Honest (with my honest personal response)

What the French taught me about Sex – for Red Magazine

Special Edition – Saleem Haddad on Shelving the Gay Novel

*POSTSCRIPT*

Next week, another powerful guest post from Sofka Zinovieff on Writing about a Taboo Subject in her bold and elegant novel Putney, which examines a grown man’s sexual relationship with a young girl and its long term consequences.

Advertisements