Regular visitors to the Sofa will know that short fiction doesn’t often pop up here, so when it does, it’s something really special. Today’s guest Amanda Huggins is the first short fiction writer ever to appear twice on the blog and the timing is perfect to congratulate her on winning the 2020 Colm Tóibín International Short Story Award with ‘Eating Unobserved’, a piece I loved for its sensuality and Parisian ambience.

Regular visitors to the Sofa will know that short fiction doesn’t often pop up here, so when it does, it’s something really special. Today’s guest Amanda Huggins is the first short fiction writer ever to appear twice on the blog and the timing is perfect to congratulate her on winning the 2020 Colm Tóibín International Short Story Award with ‘Eating Unobserved’, a piece I loved for its sensuality and Parisian ambience.

So far the Summer Reads guest programme has added two new Writers on Location posts, on Paros, Greece (Dugald Bruce-Lockhart) and Cornwall (Jane Johnson) and with Mandy’s piece today we’re panning out to look at the importance of geographical location – a real strength of her work – more generally. I’ve never mastered the art of reviewing collections, but she does a fine job of conveying the physical and emotional range of these beautifully crafted stories below; it only remains for me to add a resounding recommendation!

When I open a new book I want to be transported to another country, to a different landscape. Whether beautiful or bleak, I want to hear it, touch it, taste it, to feel as though I’m actually there – and right now this fictional travel feels more important than ever.

The stories that stay with me are always those with evocative and immersive settings, where the location lives and breathes – such as the desolate moors in Jane Eyre, Leningrad as depicted in The Siege by Helen Dunmore, or the American South in Flannery O’Connor’s short stories. More recently I’ve loved the unsettling depiction of Kiev in Judith Heneghan’s Snegurochka and the cold loneliness of a South Korean seaside town in Winter in Sokcho by Elisa Shua Dusapin.

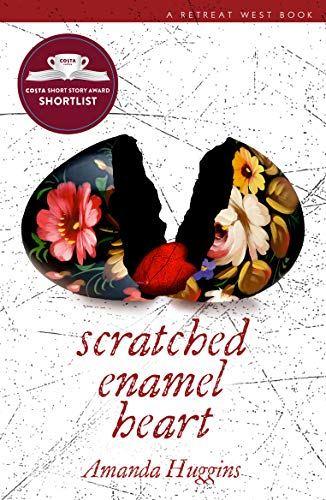

As a keen travel writer I have always tried to convey a strong sense of place in my own fiction, and in short stories this needs to be done quickly with only a few words. The stories in my new collection, Scratched Enamel Heart, are set in locations as diverse as Russia and India, Paris and Brooklyn, mid-west America and the north-east coast of England. These different landscapes often dictate the way language is used in the story, whether it reflects the lush, sensory overload of India in ‘A Longing for Clouds’ or the vast, dusty plains in ‘Red’.

My writing has always explored the vagaries of the human heart – the conflict between the struggle to connect and the need to escape, themes of love and loss, of not quite belonging. I always aim to link characters feelings of exclusion and isolation to places as well as people; countryside and cityscapes shaping and affecting lives in a myriad of ways.

A village fort on the edge of the Thar desert imprisons the free-spirited Miranda in ‘Distant Fires’. She escapes every evening by climbing onto the ramparts to stargaze and catch glimpses of the villagers’ lives by firelight. When lonely or alienated characters observe the lives of strangers in unfamiliar landscapes, they often feel even less connected to the world – such as when the nameless protagonist in ‘A Brightness To It’ talks of feeling utterly alone when drawn towards the lights of houses dotted among trees on a Greek hillside. This story is set in London in heavy snow, and the beauty of the silenced city offers a moment of hope, a cocoon of respite from the false brightness of the capital. But as the snow melts, and the city returns to its usual frenetic pace, fragile connections may melt away with it.

The characters in Scratched Enamel Heart are often searching for something intangible, seeking beauty in their lives, understanding the importance of food for the spirit. Tolya’s grandmother sums this up in ‘Nothing Like letter to Brezhnev’: “If I had only fifty kopeks, with thirty I would buy bread for my body, and with twenty I would buy lilacs for my soul.”

This search for beauty in life is linked to the landscape in ‘Where the Sky Starts’. Rowe is a young boy trapped by his surroundings on the north-east coast of England who finds himself facing the inevitability of a future working in the harsh environments of the steelworks and the fishing industry. He wants to escape from the bleakness of his home village, the power and brutish force of the sea. They are the things which have shaped his brother and mother, whose hard lives leave no room for Rowe’s more sensitive nature. Rowe knows the sky starts on top of the moors, where bees are sated on heather and where lapwings cry, not where it meets the ocean – the hostile, frightening place where his father was drowned.

As I was brought up on the Yorkshire coast there is no landscape that means more to me than the sea and the nearby moors, and consequently much of my work has the sea at its heart: the way it gives and takes, its strength and cruelty, its transformative power, its untameable beauty. Although I live inland at the moment, I return to the east coast often, and find it the most inspirational place to write; I’ve really missed it these last few months and am looking forward to going back up to Northumberland in August.

Many thanks to Mandy for this beautiful piece which conveys the depth of her connection to place(s) and the central role they play in her stories, where they are far more than just a setting. I’d also like to give a shout-out to her publishers, tiny independent Retreat West, for the important role they and other small presses play in getting top quality writing to readers when it might not happen any other way.

Here’s Mandy’s previous Writers on Location post about Japan.

*POSTSCRIPT*

Next week, for the final post before a break for whatever I can salvage of this cruel summer, it’s a big deal for me to host Justin Myers AKA The Guyliner, who’ll be writing about generational conflict and his new novel The Magnificent Sons.