Book Review by George Simmers: Maurice Walsh (1879 -1964) was a popular Irish writer, and this is a book of five interlocking stories, all of them set in Ireland of the early twenties; most of the central characters are members of a flying column of the IRA. All five are ultimately love-stories, and all link, directly or indirectly, to a prologue in which a woman, Nuala Kierley, gains access to secret military information (‘It was woman’s work, and done in the only way a woman can do that work.’) It is information that will ultimately unmask her husband as a traitor to the Republican cause, a fact that she had at least half suspected. Later the husband is found drowned.

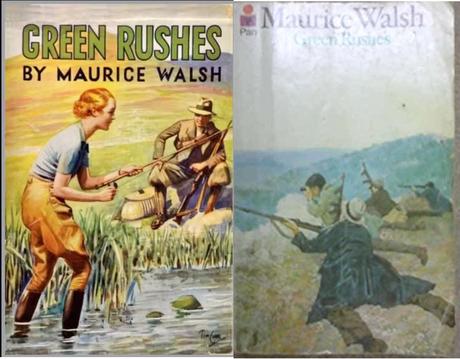

The cover of the 1935 first edition stresses the themes of love and fishing; I read a 1974 Pan paperback, which puts an IRA ambush on the cover.

The cover of the 1935 first edition stresses the themes of love and fishing; I read a 1974 Pan paperback, which puts an IRA ambush on the cover.

The first proper story is set during an IRA ambush of a column of Black and Tans (the military police force made up of ex-soldiers who enforced Britsish rule with considerable brutality during the irish war of Independence). When a decent (non- Black and Tan) British soldier – a Scottish major traveling with his sister – stumbles across preparations for the ambush, the IRA men are gentlemen, and don’t kill him, but he is taken prisoner. It is a kindly imprisonment in a secluded rural hotel, where he is allowed to fish for trout, and where his sister develops a relationship with the one of the IRA men – the story’s narrator. The announcement of the 1922 truce means that the prisoners can be released. It also means that another devoted Republican now feels himself free to marry. This happy ending is typical of the stories.

The second story is set in the aftermath of the truce, and ends with Owain the narrator, marrying the Scottish major’s sister. The Civil War lurks in the background, but does not impinge on the positive tone of the story.

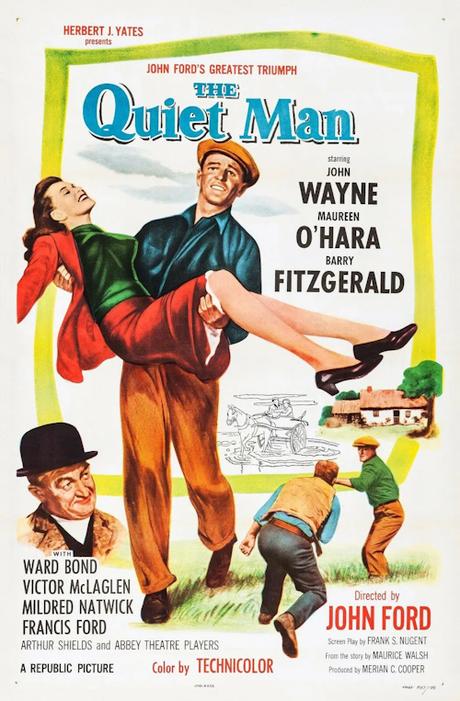

The third story, The Quiet Man’, is very much set post-Troubles. It’s the exhilarating story of a quiet man (back in Ireland after a career as a boxer in America) putting a bully in his place – not quite so exhilarating as the great John Ford film loosely based on the story – but still most enjoyable.

[An autobiographical aside: I saw The Quiet Man in Venice some years ago, at the time of the Film Festival. There was a big free screening of it in one of the squares, with a large audience. At the moment when John Wayne kicks Maureen O’Hara’s behind, there was a massive enthusiastic cheer from the assembled Italian men – the biggest cheer I’ve ever heard in a cinema.]

I’ve seen middlebrow literature described as literature that leaves readers feeling good about themselves and about their society. This collection of stories, written ten years after the events it describes, would make an Irish reader feel good about the events of the early twenties.

The violence of the Troubles is not ignored, but is downplayed. Killings happen offstage, as it were. The republican actions described happen not during the more morally controversial 1916 Easter Rising, but in the early twenties, when Republicanism was being put down with considerable brutality. The operation to ambush Black-and-Tans is laconically described by one of the book’s narrators:

I will say nothing more of that ambush than that we cut off a lorry-load of Tans, had two men killed, three wounded and a third bullet-hole through Matt Tobin’s bowler hat.

The deaths of the men in the lorry are not taken seriously because they are Black-and-Tans, who are depicted as simply villains:

The British Military Police were nicknamed the Black and tans because of their uniform -blue-black tunic and khaki trews – and because they possessed all the virulent qualities of a black-and-tan terrier gone sour.

The IRA men, by contrast, are heroic, mostly in an understated way. The men are mostly quiet, determined, and ruthless when they have to be. The women are mostly red-haired and passionate, and equally loyal to the cause. The humanity of the Republican men is shown by their friendship with Archie MacDonald, the Scottish soldier who was taken prisoner in the first story, and remains a friend thereafter.

Where works by writers like Sean O’Casey and Liam O’Flaherty, despite Republican sympathies, tend to reveal the disruptive and unsettling effect of the Troubles, Walsh is much more positive. He does not ignore the violence of the time, but it happens offstage, as it were, as background to a story which is about the bringing of harmony. These are stories that end in marriages – or in the cae of ‘The Quiet Man’ the triumphant demonstration of a marriage’s rightness.

The Irishmen of the stories are mostly farmers, but Walsh shows them as more than that. One of the characters says:

The Irish country man was not a peasant. Someone had defined him as a strayed nomad tent-dweller, forced to till the soil and till it damn badly. A farmer by necessity, a saloon-keeper by choice, a politician by ideal.

The last story comes back to the story of Nuala Kierley, the woman who betrayed her husband’s treachery for the sake of Ireland. It brings it to a positive resolution, with her able to move beyond the past, and with old quarrels and memories set aside.

Walsh writes with great gusto. There is a great deal of fishing in the book, described with expertise and love, and the fight scenes are tremendous. I enjoyed this book, and can see why it must have had considerable appeal to Irish readers in the thirties.