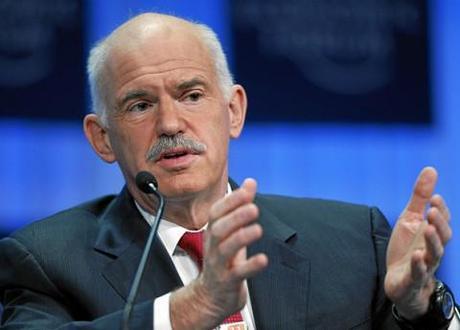

Fighting off critics: Greek PM George Papandreou. Photo credit: World Economic Forum, http://flic.kr/p/9dzUhz

At the close of this dramatic week in the eurozone, embattled Greek Prime Minister George Papandreou is struggling to cling to power: Following his shock referendum announcement of Monday, subsequent flogging at the hands of eurozone leaders and his own political allies and enemies, and decision to first amend then scrap the referendum all together, Papandreou faces a confidence vote in Greek Parliament today. And, say commentators, it’s truly up in the air whether his slim majority can survive.

Papandreou to drop referendum

Why did Papandreou do it? AFP has some ideas.

What’s the deal with the referendum? Papandreou’s initial referendum proposal would have had the Greek people voting on whether to accept the EU-led bailout and would likely have seen them voting “no”. The package would have come with more austerity measures and for that reason remains deeply unpopular with Greeks, who have watched their quality of life erode with each infusion of EU dosh; Papandreou, who has been at the helm while Greece navigates the roiling waters of austerity measures and violent public unrest, may have seen an opportunity to curry favour with the people in a show of democracy.

But not accepting the package will, EU leaders claimed, endangered the whole of the monetary union – without EU rescue funds, Greece will go bankrupt within weeks. French President Nicolas Sarkozy and German Chancellor Angela Merkel, inarguably the most powerful couple in the 17-member eurozone, demanded that Greece make up its mind – does it want to be in the eurozone at all any more? And to help the country make up its mind, Sarkozy declared that Greece wouldn’t see another euro of the rescue package, including this month’s desperately needed €8 billion infusion, until it did. Apparently, more Greeks want to remain in the eurozone than want the bailout package, so Papandreou agreed to amend the referendum to that question.

James Kirkup, The Telegraph’s deputy political editor,summed up the last week very nicely in this piece for the paper.

No more referendum. With international pressure mounting and domestic strife auguring deep instability, Greece abandoned the referendum plan; Asian markets rose sharply on the news and the euro enjoyed a rebound. But though global markets are looking a bit rosier in the cheeks following this dramatic week, the euro is still encountering “stiff resistance”, as Reuters put it – few market players and investors think that this protracted eurozone disaster will see a resolution any time soon. Now, however, whether Greece accepts the bailout depends on the outcome of today’s confidence vote and whether the prevailing political power will agree to it.

New interim government likely after PM drops referendum call, Greek paper Ekathermini reported.

Papandreou’s future. But all these political machinations have taken a toll on Papandreou and now, some outlets are reporting that Greece will back the bailout package only if Papandreou steps down. “The Franco-German intervention, backed by the International Monetary Fund, forced the pace of events in Athens as Mr Papandreou engaged in frantic talks to hold back defections from Pasok [Papandreou’s divided socialist party] while seeking a rapprochement with the country’s main opposition party,” The Irish Times explained. The opposition said it would back the deal in exchange for Papandreou’s scalp; he has reportedly struck a deal with ministers to stand down and hand power over to a coalition government if they help him get through the confidence vote, Reuters reported. Papandreou is about as popular at home right now as he is abroad: The Telegraph’s tame Labour commentator, Dan Hodges, decalred, “George Papandreou is the eurozone’s Neville Chamberlain: insular, spineless, and oblivious – or, worse, indifferent – to his broader national and international obligations.”

Default still likely. A disorderly Greek default is still a very real possibility, despite efforts to secure the bailout. But would that be so bad? Costas Lapavitsas, a professor of economics at the University of London, suspects that it might not be. According to The Philadelphia Inquirer’s Maria Panaritis, Lapavitsas is part of“an increasingly vocal minority calling for a Greek default”, on the reasoning that the debt-laden nation would have a better chance if it went its own way, away from the stronger eurozone nations who benefitted from weaker nation’s credit-soaked citizenry. A default would be “dangerous”, he said, but is a better alternative to economic stagnation.