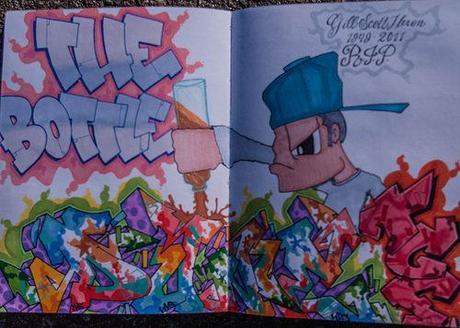

The Bottle, by DUNE UNO, Gil Scott-Heron 1949-2011

The Bottle, by DUNE UNO, Gil Scott-Heron 1949-2011

I have a bias about the future, the deep future. We can’t predict it, for it’s too strange. It’s not simply a continuation of current trends into the future. Oh, sure, there is that.

But there is also radical change, captured in the concept of a singularity, a “moment” in human history that so changes the dynamics of human society and culture than those living on the past side of it cannot imagine much less predict the nature of life on the far side.

We are now living in such a singularity. It is breaking over and around us like a 12-foot wave breaking over surfers in the Banzai Pipe. We don’t know what the world will be like when the last energies of the wave have dissipated. All we can do is be prepared to create a new way of life on those shores.

Images Images (Photos) Everywhere

I am an intellectual. My main mode of acting is through thinking. And what I am thinking is that those distant shores began appearing before us in Philadelphia and New York City in the late 1960s and early 1970s. I am of course talking about graffiti, not just any writing on walls, but the particular kind of writing that appeared on those walls at that time, writing using aerosol paint as its instrument.

At the time most good citizens thought of it as vandalism; from a legal standpoint, that’s what it is. In his essay to the first “bible” of graffiti, The Faith of Graffiti, Normal Mailer called it art. I’m calling it messages from the future.

I note first of all that we are living in a renaissance of images. Everyone has a cell phone and uses them to take photos. As a recent Google report observed:

Since the dawn of time we’ve been captivated by images. But the web has turbocharged our ability to view, share and create more imagery than ever before, to the extent that visual imagery has become the dominant form of communication in the 21st century. No wonder smartphones and tablets sans keyboards are increasingly popular – they prioritize imagery above all else.In 2011 380 billion photos were taken, that’s 10% of all the photos ever taken. Most of those photos, of course, are quick and dirty. But as people take more and more photos they will inevitably be come more discriminating. The quality will go up.

This bias towards imagery is creating a new sensorium – how we perceive and sense the environment around us. It has not only influenced how we engage in the digital space, but outside of it too.

It’s in that context that we have to think about the impact of graffiti. In an increasingly visual culture, visual imagery is ever more important. Graffiti is everywhere, and spreading. Photos of it are all over the web. Last year Google’s Cultural Institute launched the Street Art Project to showcase graffiti and street art from around the world.

From Human Origins to the Renaissance

With this in mind, let’s go back in time. While we’ve found cave paintings roughly 40,000 years old, we’ve got stone tools going back almost 2 million years. That’s important, as I noted in a review of Steven Mithen’s book on music (“Synch, Song, and Society”, Human Nature Review 5, 2005, pp. 66-85):

Obviously we have no record of these utterances, but the archeological record does have indications of cultural conservatism. The repertoire of stone tools was both limited and unchanged between 1.8 and 0.25 million years ago; Mithen gives particular emphasis to the constant form of hand-axes (164). Mithen suggests that, because their finely wrought form exceeds the practical demands of butchery, wood-working, and cutting plants, these hand-axes may have been fitness indicators in the sort of sexual selection regime Geoffrey Miller has advocated.My point is a simple one: the oldest evidence we have of specifically human cultural norms is of something that can be seen and therefor copied. Cave art, so far as we’ve discovered, is considerably newer. Other than those stone tools, cave art provides our oldest evidence of human craftsmanship.

Beyond this, I note that Ralph Holloway (1969, 1981) long ago suggested that strongly conserved hand-axe form was an indicator of social norms. Those forms could not be conserved from one generation to the next unless there was a deliberate intention to do so. One has to note the significant features of an existing axe and discipline one’s knapping motions to produce that result. That is considerably more exacting than simply producing an axe with a sharp edge and appropriate heft. The motivation behind such exacting form, then, is not practical. Nor can it be merely aesthetic, which would allow for considerable individual variation. That leaves us with a desire to conform to social norms. Given the importance of such norms, that may in itself be a sufficient motivation for their form, to serve as a visible token of social solidarity. In any event, Holloway’s observation does not contradict Miller’s, and now Mithen’s hypothesis. Norms are norms, regardless of their specific purpose and norms that serve multiple ends are likely to be particularly strong.

Now let’s turn our attention to more recent events, the European Renaissance:

Filippo Brunelleschi Invented one-point linear perspective 1377-1446

Nicholas Copernicus Championed the heliocentric view of the solar system 1473-1543

William Shakespeare Playwright often credited with inventing the modern sensibility 1564-1616

Isaac Newton Synthesized the conceptual foundations of classical physics 1642-1746

It was the visual arts that kicked off the change, not literature and not science; they followed. Filippo Brunelleschi was one of the foremost architects and engineers of the Italian Renaissance:

Besides accomplishments in architecture, Brunelleschi is also credited with inventing one-point linear perspective which revolutionized painting and allowed for naturalistic styles to develop as the Renaissance digressed from the stylized figures of medieval art.There is, of course, no assurance that the future will unfold according to patterns followed in the past. But if that happens, then our future is now being written on walls around the world.

The Case for Graffiti

Assuming that the visual arts are leading the way, why choose graffiti?

On the one hand, the “legit” art world is in turmoil. You can’t tell the hucksters from the genuine artists and, in any case, there is no definitive sense of direction. Artists, dealers, collectors, and museums are thrashing about.

Meanwhile, in the course of two decades from the late 1960s to the late 1980s graffiti made its way around the world and did so pretty much outside the art world. Graffiti represents a new starting point, a new conception of image space, and it’s the only form of abstract art to attract a mass audience.

Further, as it’s spread, graffiti has attracted other styles of art and imaging making and given birth to street art. Think of them together as an aesthetic laboratory in which all styles of art will be tested and tried. It’s through that experimentation that the enduring forms of 21st century art will first emerge, for that is where they will receive their sternest test and widest exposure.

On the walls of the world, the World-Wide Wall.