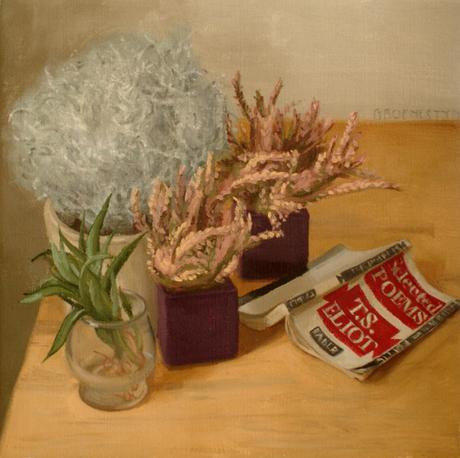

The October night © Samantha Groenestyn (oil on linen)

When one is persistently critical, sometimes people tire of you at parties, and they demand a positive explanation rather than a judgement. I’m in favour of such a broad, visionary task, but it depends on the genuine interest and attention of the questioner, because it is far more demanding and far-reaching than simply dealing with the artwork to hand. Nevertheless, when you are at a party, and someone impatiently drops the question, ‘What is good art, then?’ you feel an immense weight descend on your weary shoulders, and the magnitude of the task makes your beer-soaked brain tremble with fatigue. You scratch around desperately for somewhere to begin, but you are gripped by the certainty that you cannot bring this person to the place where you are— (T. S. Eliot):

And would it have been worth while

If one, settling a pillow or throwing off a shawl,

And turning toward the window, should say:

‘That is not it at all,

That is not what I meant, at all.’

Wittgenstein felt the futility of expounding such an explanation. When we talk about the arts, he (1966: 7) says, ‘the word we ought to talk about is “appreciated.” What does appreciation consist in?’ What happens to us when we stand before a painting, and it weaves its spell on us, and the mysterious effects that belong to good art take possession of us? ‘It is not only difficult to describe what appreciation consists in, but impossible,’ Wittgenstein (1966: 7) declares without apology. ‘To describe what it consists in we would have to describe the whole environment.’ He knows that this question is facetious, that the questioner cares little for the totality of the environment, and turns decisively to criticism as a more productive approach. He is correct, of course. But perhaps we can magnanimously respond to the genuine questioner with the beginnings of a broad, positive conception of things that contribute to the ‘goodness’ of art.

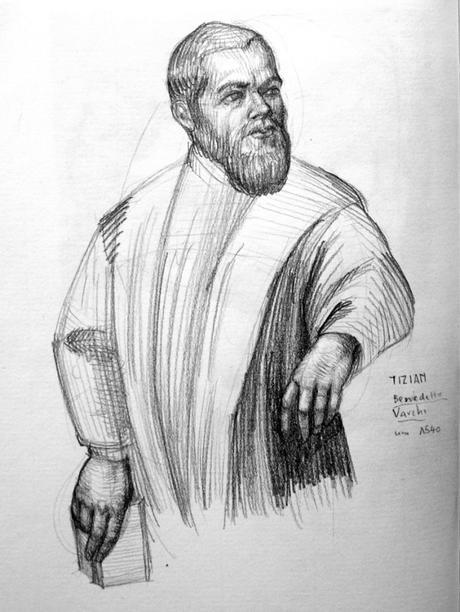

Copy after Titian

I would propose three categories of ‘goodness’ in painting (my favourite art, you’ll forgive the preference), each of which would demand long treatises to clarify just what their whole environment consists in. But their domains are helpfully distinct. The first is the technical brilliance of the work, the second is its poetic brilliance, and the third is its successful communion with the viewer.

Technical brilliance encompasses an understanding of all the elements of painting: composition, colour, texture, form, line, tone, properties of light, gesture, design, perspective, anatomy—it would be no small task to give an exhaustive list, and to deal with each component in turn. Nathan Goldstein has given much attention to this task, with admirable results. But this colossal body of knowledge is only that which any serious artist applies herself to, and finds that she needs a lifetime to master and to integrate.

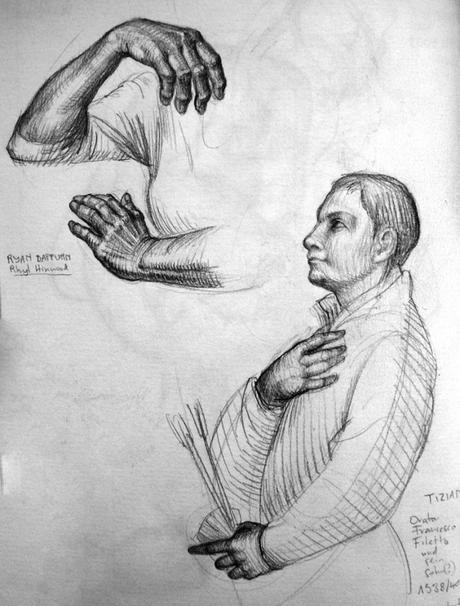

Copies after Ryan Daffurn; Titian

It is in this domain that we might speak of a painting as being ‘correct’: ‘A good cutter won’t use any words except words like, “Too long,” “All right.” ’ (Wittgenstein, 1966: 7). And a good painter makes similar corrective remarks at the gallery, consumed as she is by the technical construction of a painting. Thanks to her immense conceit, she can look at any Old Master as a mere human rival, and lament his shortcomings. But we would do well to name her an expert in this domain, since her judgements are based on knowledge of and experience in her craft.

Technical brilliance seems to be in some way evident to non-painters, but perhaps they are unable to explain exactly why. And perhaps, because of this, the real genius of a work will forever elude them. Perhaps they ought to take responsibility for learning something about the building blocks of painting in order to be able to intelligently engage with paintings, and to be able to tell a poorly-constructed painting from a well-constructed painting: ‘We want to be able to distinguish between a person who knows what he is talking about and a person who doesn’t,’ says Wittgenstein (1966: 6) unceremoniously. ‘If a person is to admire English poetry, he must know English.’

Copy after Van Dyck

But technical brilliance should be at the service of some loftier aims. Ideally, a painter has such skills at her disposal when she has some profound poetic insight—perhaps in being deeply moved by an observation or an experience. Then she is fully equipped and fully prepared to capture, to notate, to describe that insight. Her work is not simply well-executed, nor merely expressive: like an elegant equation it gracefully and satisfyingly grasps the essence of that insight. It is poetically brilliant for expressing it in an eloquent way. There is nothing forced, or stilted, or lacking; nothing fussy, nothing overstated. All the technical elements that are used weave seamlessly into each other and strengthen each other in a wholly integrated way.

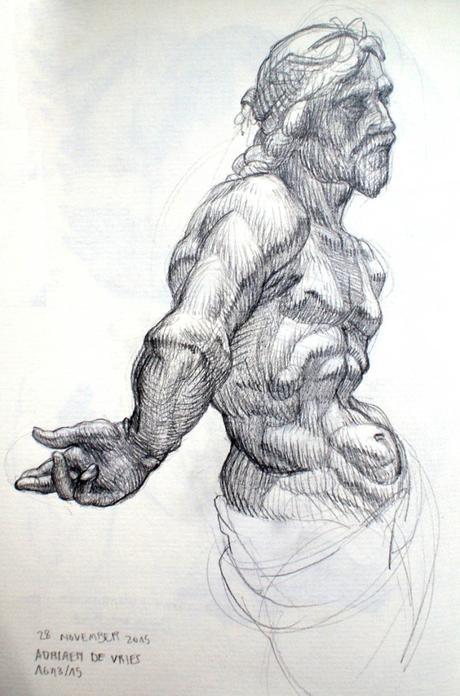

Importantly, as the ever exacting Adrien reminds me, it is not only artists who are capable of such insights. But as he explains his painfully recognised inability to grasp the significance of such moments, of lacking a means of savouring them and perhaps saving them and sharing them, I begin to see that the artist has some responsibility to meditate on these themes on behalf of everyone else. She is no more insightful than anyone else, but perhaps she is particularly attentive to the profound in the mundane, particularly sensitive to the poetic in life, and, as noted, has a means of distilling them into an object, with the aim of planting these insights into souls of others.

Copy after Adriaen de Vries

And here is the final measure of ‘goodness:’ the painting’s capacity to work some effect in the viewer. We speak in metaphor: the painting moves us, it touches us. That insight, so poetically captured in the luscious strokes of paint, carried in the marks, is recreated in the mind of the viewer. Wittgenstein is firm in separating the satisfying way something is constructed from the profound way in which reaches into us. He writes (1966: 8):

When we talk of a Symphony of Beethoven we don’t talk of correctness. Entirely different things enter. One wouldn’t talk of appreciating the tremendous things in Art. In certain styles in Architecture a door is correct, and the thing is you appreciate it. But in the case of a Gothic Cathedral what we do is not at all to find it correct. It plays an entirely different role with us. The entire game is different.

Ideally, the good painting, too, transcends its technical proficiency, and does more than record a private contemplation, reaching into the thoughts of the viewer and having an irresistible sway over them, moving the viewer and giving his thoughts a heretofore unrealised expression. And this two-way communion is significant: the painting does not simply implant a thought in the viewer, but merges with the thoughts of the viewer. He needs to close the circuit: he needs to make the connections, be they technical or poetic. He needs to seek out the linear rhythms, acknowledge the deliberate variation of edges, perhaps, or consider the subdued contrast in tone; he needs to recognise with what economy and fluency the picture was created, to read the sure hand of the painter. But he should equally bring his own thoughts to the painting, for it is this private reverie that the painting seeks to connect with.

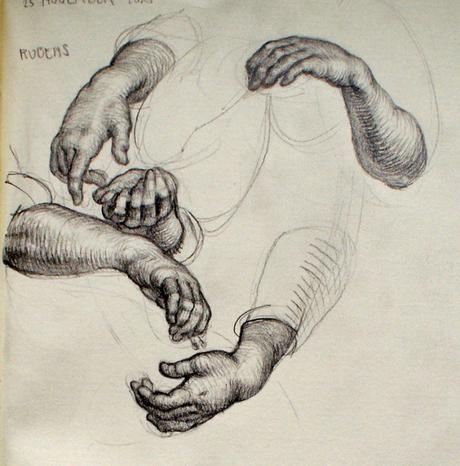

Copy after Rubens–tracing them connections

We undoubtedly share common mental experiences, and a good painting unites us in savouring the grandeur of these private moments. A good painting speaks for all of us, where ‘es fehlen uns die Worter’—‘our vocabulary is inadequate’ (Wittgenstein 1953: 159). Good paintings constitute a different language for those quiet but shared insights for which ‘we lack the words.’

Copy after Brueghel

Eliot, T. S. 1966. Selected poems. Faber & Faber: London.

Goldstein, Nathan. 1989. Design and composition. Pearson: Boston.

Wittgenstein, Ludwig. 1953. Philosophische Untersuchungen / Philosophical Investigations. Trans. G. E. M. Anscombe. Basil Blackwell: Oxford.

Wittgenstein, L. 1966. Lectures and Conversations on Aesthetics, Psychology and Religious Belief. Ed. Cyril Barrett. Basil Blackwell: Oxford.