50 years ago, I saw Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho for the first time. It was 1965 and though the film was originally released in 1960, its immense popularity led to a re-issue five years later. Thankfully, by 1965 my parents considered me old enough, and so one spring evening I ventured with friends to the Ritz Theatre in Escondido, California, to see it. Odd as it may sound, somehow I wasn't aware of every twist and turn in the plot or the shocking finale by then. Which must be why, after barely getting through Marion Crane's brutal demise, I let out a spontaneous, ear-splitting scream when "Mrs. Bates," knife in hand, ambushed Mr. Arbogast on the staircase. Later on, like so many others, I left the movie house completely unnerved and with a newly acquired skittishness about taking showers...

I'd seen Psycho a time or two on TV after that but, unlike many of his other works, it wasn't a Hitchcock film I watched again and again. Though it's as precision-crafted, suspenseful and shrewd as one expects of Hitchcock's best, I think, after having been traumatized that night at the Ritz Theatre, I developed an underlying uneasiness with the movie. But that didn't detract from my admiration for what Hitchcock pulled off with Psycho, so when I found out that the "chiller-thriller"/horror classic would return to theaters for special screenings on Sept. 20 and 23, there wasn't a chance I'd miss it.

I'd seen Psycho a time or two on TV after that but, unlike many of his other works, it wasn't a Hitchcock film I watched again and again. Though it's as precision-crafted, suspenseful and shrewd as one expects of Hitchcock's best, I think, after having been traumatized that night at the Ritz Theatre, I developed an underlying uneasiness with the movie. But that didn't detract from my admiration for what Hitchcock pulled off with Psycho, so when I found out that the "chiller-thriller"/horror classic would return to theaters for special screenings on Sept. 20 and 23, there wasn't a chance I'd miss it.I didn't cry out during the 2pm screening of Psycho at San Rafael's Century Regency Theatre on September 20, but I did feel a twinge of foreboding as we entered the theater and when the lights went down inside, I turned to my friend, Mike, and whispered, "here we go," with a nervous laugh.

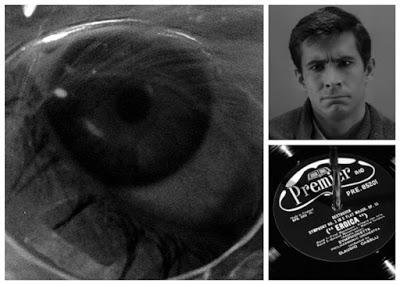

With Saul Bass's jarring title sequence and Bernard Herrmann's frenetic accompanying score, the mood is quickly set and the groundwork laid for the unsettling tale about to unfold.

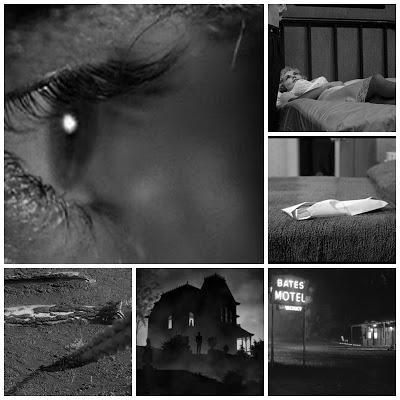

The opening credits end with a long shot of downtown Phoenix, Arizona. From here the camera pans to a nondescript hotel, zooms to one of its windows, slips over the sill, beneath venetian blinds and into a room where a pair of half-dressed lovers regard each other. It seems a sordid scene; these are the last moments of a lunch-time tryst. Then we learn that the two are in love but can't afford to marry. The woman, doe-eyed and voluptuous Marion Crane (Janet Leigh), is especially distressed by the situation. After she returns to her job as a secretary at a small, dull real estate firm, she succumbs to temptation when she is asked to take a client's $40,000 - in cash - to the bank.

While it isn't unusual for a Hitchcock heroine to have a dual nature or even a double life (Alicia Huberman in Notorious, Margo Wendice in Dial M for Murder, Francie Stevens in To Catch a Thief, Madeleine Elster/Judy Barton in Vertigo, Eve Kendall in North by Northwest), Marion Crane is one of the more intriguing of these inconsistent creatures and Hitchcock takes care to ensure audience identification with her. As she drives from Phoenix, intending to go to her lover with the money that will allow them to finally marry, the director purposely steers the audience to her subjective view. Now we hear the thoughts that run through her head, we see everything she sees - on the road and in the rear-view mirror - from her point of view.

Marion sees her boss, and he sees her, as she leaves town

A suspicious cop won't seem to go away

A blinding rainstorm leads to a wrong turn

Naturally, when Marion feels anxious or relieved so do we, for by this point we are engrossed in her dilemma and have no reason to doubt that she is our protagonist. By and by, she pulls up to the Bates Motel where innkeeper Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins) welcomes her in out of the rain, remarking on the bad weather with "Dirty night!" In a while we will realize what an understatement that is.

Norman, on first impression, seems an eager-to-please, twitchy youth who, it becomes clear, has a "mother problem." He's not Hitchcock's first off-kilter mama's boy; before Norman there was Uncle Charlie in Shadow of a Doubt and Bruno Anthony in Stranger on a Train. But Norman's personality emerges more gradually than theirs and is fully revealed only in the last minutes of the film. Most of the time the audience, like Marion, imagines him to be the troubled son of a domineering madwoman. However, we will continue to share Marion Crane's perceptions for only a short while longer.

A last look from Marion's point of view

45 minutes into Psycho the story suddenly shifts. With Marion's murder in cabin #1 at the Bates Motel, the narrative of a desperate woman on the run with stolen money is over. When Norman unwittingly tosses the newspaper-wrapped $40,000 into the trunk of Marion's car along with her body and her belongings, a new, prominently gothic, mystery is introduced.

Haunted House: The Bates home, a desolate Second Empire Victorian

The grisly early death of Psycho's central character and only star breaks an unwritten movie law, further disturbing an already anxious audience. For a while, Hitchcock engages us in Norman's point of view, culminating in a scene at a swamp, where we observe through his eyes as Marion's car sinks slowly into the mire. Though the audience is maneuvered into complicity with Norman as he covers up Marion's murder, identification with him is fleeting, for to know him too well would give away too much.

The dark universe of Norman Bates

Two years after Psycho shook the world, Alfred Hitchcock talked with his friend, critic/filmmaker François Truffaut, about its making. He explained that a good part of the film was intentionally designed to misguide the audience, and he admitted that the entire section covering Marion Crane's personal drama was an elaborate audience distraction crafted to build up to and heighten the effect of her abrupt murder. It was a fascinating gambit, he said, "I was directing the viewers. You might say I was playing them, like an organ." At this he succeeded beyond anything he might have imagined and it was the audience response to Psycho that pleased him more than anything else. He was deeply gratified that "the construction of the story and the way it was told caused audiences all over the world to react and become emotional." He recognized that the subject matter might be low-budget B-fare, but he wasn't bothered by that. "It's the kind of film," he said, "in which the camera takes over. Of course, since critics are more concerned with the scenario, it won't get you the best notices, but you have to design your film just as Shakespeare did his plays - for the audience."

Audience members at Psycho's premiere, New York, 1960

The gothic horror/crime procedural that follows Marion's journey to her murky grave terrorizes and confounds the audience up until the climactic reveal. This scene and Norman's final soliloquy resolve the mystery of Norman Bates but theater goers, drained by 109 minutes of jolting sights and sounds, are left stunned and unable to shake a lingering case of the creeps. They have been "aroused by pure film," as Hitchcock put it.

~

I'm happy to report that since seeing Psycho at the Century Regency on September 20th, I've recorded it and watched it twice. These days I feel a little like Scottie Ferguson who, in Vertigo, had to climb those bell tower stairs a second time without losing his equilibrium before he could conquer his acrophobia...