Edith Schiele in gestreiftem Kleid, Egon Schiele (1915)

Sometimes life forces you to consider what it is to be a woman—what it is to be strong, or weak; made of flesh; delicate, desirable, dependent, but harbouring a secret energy, perhaps afraid to brandish that energy, afraid to even look at it. Our bodies establish us as the weaker; our learned timidity keeps us so. The Belvedere exhibition on Die Frauen is probably intended as a feminist statement, somewhat ironically presented through the eyes of male painters. But statements aside, being enclosed in that space with all the loveliness and misery and secrecy of womanhood is a comforting experience.

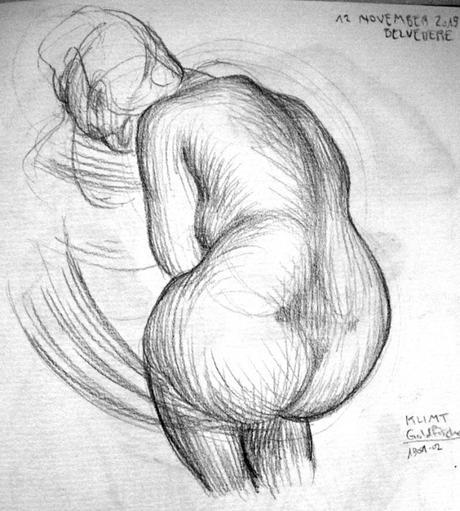

Marie Henneberg, Gustav Klimt (1901-02)

Klimt is delicate with his women, barely dusting their flesh with airy flecks of paint, as though too respectful to touch them directly. His hatched paintings are among my favourite of all his work, and seem to be an exploration in the way colours converge and diverge as he sets different hues against each other and watches the interplay between them. You experience them differently at close range and at a distance. From afar, Marie Henneberg (1901-02) and Hermine Gallia (1903/04) dissolve into smoky purple salons, at one with their sumptuous surroundings, but up close their skin and rippling dresses are a confetti of oranges, blues, greens, purples and pinks. Most colours are neutral, and the most unadultered are some moderately used cobalt blues and pale oranges. Staring at them reinforces my conviction, acquired from experience, that purple is brown—this gentle gradation of neutrals that shifts the ratios of red and blue and yellow. My best purples always contain yellow—counter-intuitively sabotaging their vibrancy with their complementary. Klimt playfully explores these fluctuations with these floating strokes laid side by side.

There is something so satisfying, then, when you get near enough to see Frau Henneberg’s eyes and their lively chestnut brown leaps out from the other purple-browns, rich and chocolatey, far more vivid than the subdued though deep brown of her hair. Klimt has found the threshold between purple and brown and knows how to make them sing. At a distance, silvers emerge from the purple, but these greys are so controlled, so luminously coloured. The slightest shift toward orange gives them an entirely different character to the purple, though one only sees it as they begin to melt into each other.

Copy after Klimt: Hermine Gallia

These women are as ethereal as the lace they are draped in, their skin shimmering, arms ‘braceleted and white and bare [But in the lamplight, downed with light brown hair!]’ (Eliot, 1966: 13). But none of their finery—pleasingly designed as it is—compares with the grace and dignity of their hands and faces. Frau Gallia is like a droplet of water, plunging heavily to the ground, but wholly self-contained; one liquid shape. And the undersides of chins, thrusting the squareness of the matured womanly jaw, projecting the distinctive shape of the downturned and slightly-parted mouth that Klimt draws obsessively again and again—this uncommon view is seductively condescending. There is something submissive in it, but something defiant. Besides which, the shapes are irresistible.

Copy after Klimt, Goldfische (1901/02)

It’s wonderful to see walls of drawings by Klimt, all lightly scribed onto aging brown paper. But there is a certain carelessness in his drawing, as though he is impatient to paint. He finds the edge with cloudy scratches, defining thighs and knees with dark negative space instead of positively asserting the body itself, and even then without conviction. Perhaps because these hurried visual notes are not conceived at all in lines but in shapes and textures. And indeed he captures some deliciously-shaped forearms, put down with great simplicity. For Klimt never seems to trust his lines, or perhaps never cares for them. He must be thinking in paint: in ill-defined expressive edges which can never be pinned down in pencil.

Edith Schiele, Egon Schiele

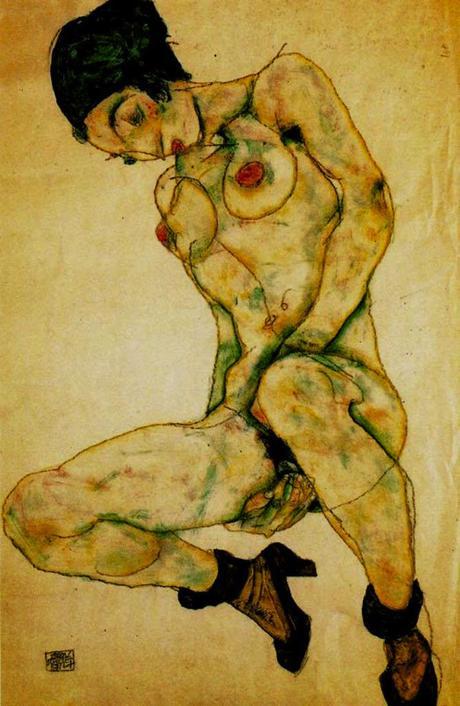

Now Schiele—das ist eine andere Sache. The boy is all about the lines. Every line is raw with passion, deliberately ravaging the page or the canvas. There is no delicacy in Schiele, even when he tenderly tries to put down the sweetness of his wife. His tenderness still brews from a deep violence coursing through him. His paintings burst with a subterranean fury: confronted with them in the flesh, I feel like he didn’t so much paint them as form them from the very earth. Despite the purity of the pinks and oranges and blues, the whole surface is a muddy terrain of paint with a very physical topography.

It’s hard to decide whether Schiele lovingly traces Edith’s jaw or forcefully defines it himself. In drawing, in painting, he dominates her, he aggressively creates her for himself; she is at the mercy of art and of the artist, terrorised by his violence. He brutally coaxes out the wild creature inside the woman, urging it with the monster inside him. When I look at his sure, sizzling lines, I feel certain that we can never see ourselves except through the ruthless description of an artist. And yet, I think it would be limiting to say that Schiele’s work is simply ‘expressive,’ despite the force of his gaze. I am sure that Schiele really sees, and really exposes something of the sitter. He seizes the defining factors in an instant—the sloping brow, the crooked nose—and his own charged insights hang from this honest scaffolding. I am sure that Schiele saw Edith’s pain: it lingers in her eyes, in the corners of her mouth. Nothing escapes his sensitive gaze, however fierce his pencil.

Copy after Schiele

His drawings always present a deeply satisfying unity. He sees the parts and he sees the whole. Each breast, the pelvis, thighs and calves, all individually carved out with such a sense for weight and balance, and yet arranged as interlocking shapes into one carefully balanced shape. As in the Mastubierender Akt mit grünem Turban (1914), which seems to hang sideways, giving her the impression of floating blissfully through the air, he is willing to assert her delicious curves in all their forceful simplicity. You feel her, you feel her stomach sucking in, her legs tensing, the balanced unity of her weighted parts.

Mastubierender Akt mit grünem Turban, Egon Schiele (1914)

It’s hard to look at Schiele’s drawings without feeling violated. Naturally, they are overtly sexual, but more than this: they pierce the soul of the subject. Sometimes it is like looking at an animated corpse. The rich, brown, leathery skin, full and lively, galvanised, but stiff and arranged unnaturally. The hands are the most arresting. All these women with meaty, bony, monstrous hands, the joints bloody and red. His women cannot be inactive with such square-knuckled, muscular hands. They are almost a challenge to action, a defiance of supposed feminine delicacy, of fragile wrists and gently tapering workshy fingers. Schiele reflects women back to themselves as something stronger.

Arms that lie along a table, or wrap about a shawl.

And should I then presume?

And how should I begin?

Eliot, T. S. 1966. Selected poems. Faber & Faber: London.