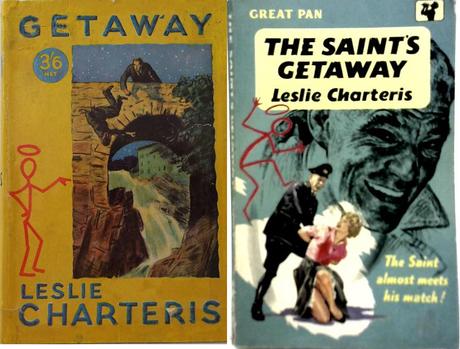

Book review by George Simmers: This is the ninth of the Saint books to be published, later it would be retitled The Saint’s Getaway, to make sure, I suppose, that potential readers were in nno doubt that it belonged to Charteris’s immensely successful series, about Simon Templar, the crime fighter who is also a carefree swashbuckling law-breaker.

The 1932 cover, and one from the sixties.

The 1932 cover, and one from the sixties.

This book begins with Simon Templar and two friends taking a holiday in Innsbruck. The Saint has resolved to put his buccaneering criminal career behind him and from now on to be ‘as good as gold’.

That resolution is explained in the book’s prologue, and it lasts about half way through the first paragraph of Chapter One. The Saint and his friends see three thugs attacking a man on a bridge, and his instincts insist that he intervene: ‘

In his ears the scuffling undertones of the battle were ringing like celestial music. He was lost.

The Saint and his friend Monty soon despatch the three thugs, throwing them off the bridge into the river – but things become complicated when the man they have rescued does not want to talk to them. Intrigued, they carry him back to their hotel, where he is murdered. They are in the middle of a gang war of some kind – and what is more, they realize that the three attacking thugs were policemen. So by the end of chapter one they are in the classic thriller situation, up against not only criminals, but the police as well.

The plot thickens when they realize that one of the opposing groups is led by an old antagonist of Templar’s: Crown Prince Rupert of Brat, ‘the stormy petrel of the Balkans, the outlaw of Europe, the man who in his own strange way was the most fanatical patriot of the age, marvellously groomed, sleek as a sword-blade, smiling…’

From there onwards the action hardly slackens for 187 pages, as the Saint and his friends hurtle from one exploit to another, lured by the prospect of getting their hands on the Crown Jewels of Brat.

In a preface to my 1965 edition, Leslie Charteris apologises for his depiction of European politics as being out of date even in 1932, though Hitler was not yet within reach of power. He excuses himself by saying that: ‘The kind of mythical principality ruled by Prince Rupert was still loosely acceptable to the popular imagination, at least as a nostalgic tradition.’ Indeed so, and I think the reason for Ruritanian politics featuring in fiction of the twenties is that many in Britain and elsewhere would have had a sense that the Great War had arisen out of a Balkan squabble about Serbia, a country of which most British people knew little. Ruritanian conflicts contained the possibility of destabilising the world – much as Middle Eastern ones do today.

As I have said, the action is unrelenting. Dead bodies are strewn everywhere without much compunction. There is a thrilling sequence on a train, and a daring attack on a police station. Throughout everything the Saint keeps up his appearance of sang-froid, though occasionally we are given an insight into the strain it takes to maintain his elegantly breezy exterior. I’ll give an example later.

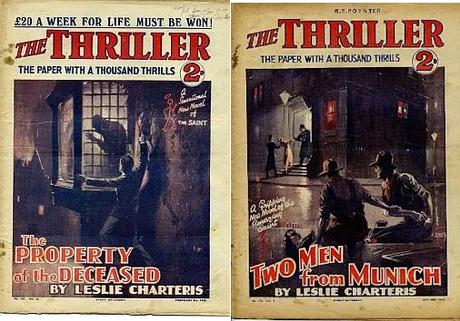

His friend Monty Hayward is an interesting character – and a bit of an in-joke. Monty Hayward is the editor of a crime-story magazine, and is clearly based on Monty Haydon, the editor of The Thriller, the magazine in which this book first appeared in two instalments. Monty is conflicted. Unlike Simon Templar, he is basically a respectable citizen but when the lure of adventure calls, he always rises to it, and joins in manfully, knocking policemen over the head without compunction.

The issues of ‘The Thriller’ which formed the basis of ‘Getaway’

The issues of ‘The Thriller’ which formed the basis of ‘Getaway’

The Saint’s girlfriend, Patricia Holm, is also in evidence. Like Monty, she shows initiative and commitment to the cause, but she is also there for the reason that girls are usually there in thrillers – she is captured by the enemy and needs to be rescued.

The book’s language is often as exaggerated as the story’s melodramatic situations. Hyperbole abounds, as does facetiousness of the same hind that the saint used to confuse his adversaries. There are good phrases: the modernist architecture of a police station is described as ‘that cubist bellyache of a fortress.’

There is a great deal of over-writing, in a style that matches the absurdity of the plotting:

And yet before the last words were out of his mouth Simon Templar had seen a thing which crushed every other thought in his head. It burst in his senses with the stupefying concussion of an exploded bomb, gripping his brain in an icy constriction of sheer paralysis, so that for one heart-stopping instant the whole world seemed to stand still all round him. And then the full torrent of comprehension weltered down him like a landslide and shattered the fragile stillness as though it had been held in a gigantic bubble of glass, blasting the shredded fragments of his universe in a swimming vortex of incoherence that made the blood roar in his ears like a hundred dynamos.

Leslie Charteris knows that fans of the Saint enjoy this sort of thing. Some more serious connoisseurs of literature, I know, don’t. When I was about thirteen, I thought the Saint was the last word in sophistication. Now I’m interested in how he came to be created. Leslie Charteris was half-Chinese, the son of a doctor. He had a miserable time feeling like an outsider in an English public school, and his revenge against the Establishment is his creation of a sensational fictional outsider and rule- breaker, elegant, glamorous, uniquely skilled in the arts of knife-throwing and repartee, unfazed by any situation. And the character struck a chord in the popular imagination; his success was extraordinary.