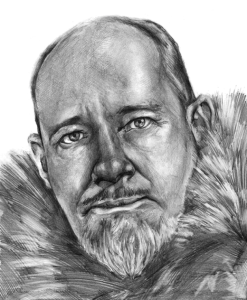

As many of you know, I have held the ‘Sir Hubert Wilkins Chair of Climate Change’ at the University of Adelaide since January 2015. My colleague and friend, Barry Brook, was the foundation Chair-holder from 2006-2014.

As many of you know, I have held the ‘Sir Hubert Wilkins Chair of Climate Change’ at the University of Adelaide since January 2015. My colleague and friend, Barry Brook, was the foundation Chair-holder from 2006-2014.

Initially set up by Government of South Australia to “… advise government, industry, and the community on how to tackle climate change …”, it now is only a titular position based at the University. While I certainly try to live up to the aims of the Chair, it’s even more difficult to live up to the namesake himself — Sir George Hubert Wilkins.

Given I’ve held the position now for over a year and half, I’ve had plenty of time to read about this legendary South Australian (I do choose my words carefully here). Despite most Australians having never heard of the man, it is my opinion that he should be as well known in this country as other whitefella explorers such as Douglas Mawson, Matthew Flinders, Robert Burke, William Wills, and Charles Sturt.

Sadly, he is not well-known, for a litany of possible reasons ranging from spending so much time out of Australia, never having a formal qualification in many of the skills in which he excelled (e.g., geography, meteorology, aviation, engineering, cinematography, biology, etc.), disrespect from other contemporary Australian explorers, and some rather bizarre behaviour later in his career. The list of this man’s achievements is staggering, as was his ability to thumb his nose at death (who, I might add, tried her hardest to escort him off this mortal coil many times well before a heart attack claimed him at the age of 70).

Many books have been written about Wilkins, but as I slowly make my way through some of the better-written tomes, one unsung aspect of his career has struck a deep chord within me — it turns out that Wilkins was also a extremely concerned biodiversity conservationist.

Just the other night, in fact, I was invited to speak at the State Library of Australia about Wilkins scientific exploits. As I mentioned above, he wasn’t a trained scientist, but promoted the concept of a world meteorological measurement network that we all take for granted today, was near-fanatical about taking scientific measurements whenever he was exploring, and promoted scientific discovery as one of the main objectives of all of his explorations.

One story is wonderfully demonstrative of his single-mindedness and determination. In an attempt to discover a mythical northern continent in the Arctic, in 1927 he and pilot Carl Ben Eielson were once forced to land — for the first time — on a small stretch of relatively smooth sea ice somewhere north of Wrangel Island. Not only is the landing itself quasi-miraculous, while Eielson was tending to their aeorplane’s engine troubles, Wilkins busied himself with digging a hole in the metre-thick ice to take one of the Arctic Ocean’s first depth soundings; his data suggested a depth of 5600 m†, and was the first real sign that perhaps the mythical northern continent didn’t exist (of course we know now that it doesn’t). Taking a few measurements (and digging a few ice holes) for confirmation, they promptly resumed their journey north, only to be forced back toward Alaska due to fuel concerns. In fact, that return trip is an even more miraculous tale of survival — Eielson and Wilkins ran out of fuel some 200 km from the Alaskan coast, landed the aircraft in the dark and in a blizzard on the only stretch of landable ice for kilometres around, and then trekked the distance back to Alaska over the next 13 days. The worst consequences of the journey was that Eielson lost a few knuckles worth of little finger from frostbite. The very next year, Wilkins and Eielson successfully made the world’s first trans-Arctic flight (Alaska to Spitsbergen) in 20 hours.

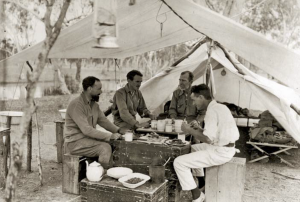

The scientific staff of Wilkins’s northern Australian expedition. From left to right: George Wilkins, leader of the expedition; Vladimir Kotoff, mammalogist; J Edgar Young, botanist; O G Cornwell, Ornithologist. Byrd Polar Research Centre Archival Program

It’s easy to digress when writing about Wilkins.

Back to the main point of my story. Several years before those Arctic adventures, Wilkins was employed by the British Museum (Natural History Division) to explore the north of Australia (particularly northern Queensland, the Gulf Country and Arnhem Land) to collect specimens of dwindling Australian wildlife. The expedition took him 2.5 years, during which time he collected many species new to science (two of them — a rock wallaby Petrogale wilkinsi and a slider Lerista wilkinsi were named after him). His personal account of the adventure is told in his 1928 book Undiscovered Australia§ on which the event this week was centred.

I haven’t read the book yet, but I’ve read many other bits that refer to his writings therein. This is where it gets interesting from a conservation perspective — throughout the book, Wilkins remarks in many different ways about the following phenomena:

- the fauna in northern Australia are disappearing quickly

- deforestation by farmers and settlers is alarming and contributing to the biodiversity crisis

- most people couldn’t give a flying 𝒇μ¢κ about the environmental catastrophe unfolding

Doesn’t that all sound woefully familiar? Yes, we lead the world in ‘modern’ mammal extinctions, many of which Wilkins himself was witnessing back in the 1920s. I’ll give you one poignant quote from the book:

“We found the hills more barren and more destitute of game than the coastal areas. The longer we hunted and the more reports we heard, the greater was the evidence that Australian native life is rare in many places and extinct in parts.“

Now I’m something of a student of the history of the Australian environmental movement, about which I’ve written in my recent book Killing the Koala and Poisoning the Prairie with Paul Ehrlich. I’ll quote a relevant snippet that contextualises Wilkin’s observations and sentiments:

Even as far back as 1803, and only five years after the First Fleet landed in the area that was eventually to be called Sydney, the Governor of New South Wales, Philip Gidley King, ordered that trees along the Hawkesbury River were not to be cut down due to erosion concerns. His orders went largely unheeded by the development-hungry colonists. Later in 1865, a report issued to the Victorian Parliament complained that over-exploitation of forests would soon leave little timber for the requirements of other industries such as mining. Other government botanists, clergyman, doctors, private citizens and even early feminist artists also complained bitterly about the wanton destruction of forests as the colonial wave passed through the country. For the most part though, their cries went unheard or were completely ignored.

Australia’s first national park was created in 1879 on the outskirts of Sydney. While the establishment of the 7300-hectare (18,000-acre) ‘The National Park’ (as it was known, now the ‘Royal National Park’) was most likely inspired by the creation of Yellowstone National Park in the US seven years earlier, the two areas had very different purposes. Yellowstone was created primarily to preserve its natural wonders from development for the benefit of all Americans, whereas ‘The National Park’ in Australia was created primarily for the sport and recreation of the 200,000 citizens of the colony’s largest urban centre, Sydney, only 20 kilometres to the north. As such, preservation was an extremely low priority, with uses such as ornamental plantation, zoological gardens, race courses, artillery ranges, mining, timber felling, livestock grazing and deer husbandry all permitted.

Although these decidedly non-conservationist activities were eventually excluded, their legacy still weighs heavily on the region’s biowealth. Subsequent parks were established around the country, and as for ‘The National Park’, primarily as recreational respite from urban living around the country’s major population centres – these included Belair in South Australia (1891), Ku-ring-gai Chase north of Sydney (1894), Witch’s Falls and Bunya Mountains near Brisbane (1908), Cunningham’s Gap also near Brisbane (1909), Lamington near the Queensland-New South Wales border (1915)60 and Mount Field in Tasmania (1915 – later revoked). The first Australian national park created more in the spirit of Yellowstone was probably Mount Warning in the far northeast of New South Wales in 1929. This was followed by Dorrigo Mountain in 1930 and New England National Park in New South Wales in 1937. Australia’s largest national park, Kakadu National Park in the far north of the Northern Territory, was declared in three stages between 1979 and 1991.

Bradshaw & Ehrlich 2015,

Killing the Koala and Poisoning the Prairie,

University of Chicago Press

What this demonstrates was that despite a few complaints from some few enlightened citizens in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Wilkins appears to be among the first of the well-respected and highly influential Australians to raise the alarm about what was happening to Australia’s environment. In fact, it really wasn’t for another 30-40 years that any semblance of environmental protectionism took hold among at least some part of Australian society.

I therefore contend that Wilkins was one of the first whitefella conservationsists in Australia, and by rights should be viewed as the father of modern Australian environmentalism. He deserves a place in history as grand as (if not grander than) Rachel Carson.

I hope this recognition will take some root. Without attempting to steal any of his explorer thunder, in my view the most laudable aspect of the great Sir George Hubert Wilkins was his concern for the natural world around him.

—

†Later soundings identified that Wilkin’s measurement was a tad generous, with the actual depth closer to 3500 m. Still.

§Admittedly, a culturally insensitive title that dismiss more than 50,000 of human history in Australia.

CJA Bradshaw