One does not find one’s people wherever one goes. Kindred spirits are harder to find, even among those with common interests. The minds that encircle me—those rare few among the many who draw, paint and write—immediately evinced to me a particular harsh quality, a certain incisiveness of thought, a terrible dismembering inquisitiveness, and an undeniable probity in their search for solid principles, for secure footing. These minds apply their powers to questions in ethics, in quantum mechanics, in political theory, in painting, and in every field they shun the mysticism that sparkles around the unstable ground of chance. For as Baudelaire (1972: 65) would have it: ‘There is no such thing as chance in art any more than in mechanics. A happy idea is no more than the consequence of sound reasoning.’

We were thus irresistibly drawn together by a common inquiring impulse. We formed each other in that especially malleable phase of life, reflecting each other’s ideas and words back at each other, finding common concepts and developing consistent vocabulary. Our ideas were strengthened by this validation, deepened by the many viewpoints, tested and stretched out and proven. We constructed our own language, our own way of speaking about these matters, seizing upon terms from those we looked up to, from books, sometimes importing terms from parallel concepts in our complementary fields. And this language is of supreme importance to people like us: because we demand precision. We preference the specific over the mystical and the vague. Our inclination to pull things apart demands a precise vocabulary in order to speak about the patterns we discover, to organize them and to piece them back together. Our approach might well be considered analytic, since we push onwards by first pulling apart and inspecting the parts, carefully piecing them back together. And when I finally found painters who operated this way, I latched onto them fiercely. Painting profits from this near-scientific precision, though most people would prefer to cast art in with magic. Our precision only turns up more profound questions.

For anyone can throw paint around and delight in improbable new constellations of color. We revelled in this in purest glee in childhood: ‘The child sees everything as a novelty, the child is always “drunk,”’ Baudelaire (1972: 398) observes, and while this vague dizzy delight is essential, it is by no means sufficient. Our compulsion to understand harnesses this childlike drunkenness and directs it wilfully and powerfully. ‘Genius is no more than childhood recaptured at will, childhood equipped now with man’s physical means to express itself, and with the analytical mind that enables it to bring order into the sum of experience, involuntarily amassed’ (Baudelaire 1972: 398).

Order! How unromantic! Such a cold and diffident regime to impose upon art! Yet why should it be so? The painters I look up to continually show me that there is a way through the nonsensical mess if one pays attention and works systematically, and their work grows in depth and facility day by day, in embarrassing contrast to the stagnation of those who deny it. Richard Wagner’s musical abilities were mistrusted for ‘the very breadth of his faculties and his high critical intelligence,’ (Baudelaire 1972: 340). ‘“A man who reasons so much about his art cannot produce beautiful works naturally,”’ it was complained (Baudelaire 1972: 340). But it is this blind trust in nature that thwarts the intelligent production of art.

This notion of working ‘naturally’ denies that art, too, is work, that it must be learned, trained, cultivated, challenged and advanced. It longs for the subtle result, the piece lightly breathed into existence, the confident strides of an effortless creator. But these are the very refinements that only come with dedicated and focused work. The untrained hand is clumsy. We should not forget that nature, while she surges on with profuse energy, delights in wild, self-devouring frenzy more than subtlety and harmony. ‘Review,’ challenges Baudelaire (1972: 425), ‘analyse everything that is natural, all the actions and desires of absolutely natural man: you will find nothing that is not horrible. Everything that is beautiful and noble is the product of reason and calculation.’ The artist tames nature, moulds nature imperceptibly, crafts mesmerising variations upon it that captivate us precisely because they are tailored to us, rather than wild. ‘Things seen are born again on the paper, natural and more than natural, beautiful and better than beautiful’ (Baudelaire 1972: 402). A sensitive and intentional distillation of nature takes place as the raw materials of nature ‘are classified, ordered, harmonised, and undergo that deliberate idealisation’ by the skilled artist (Baudelaire 1972: 402).

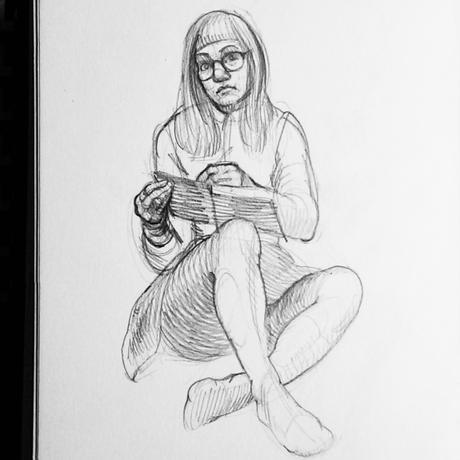

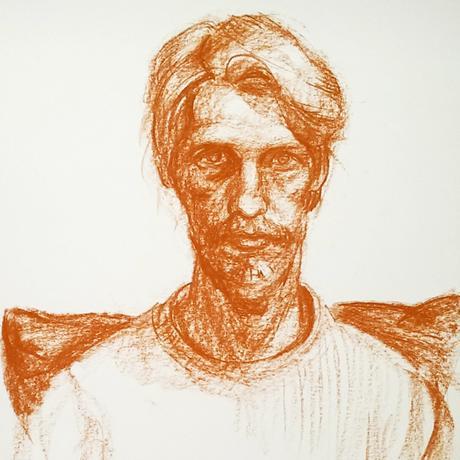

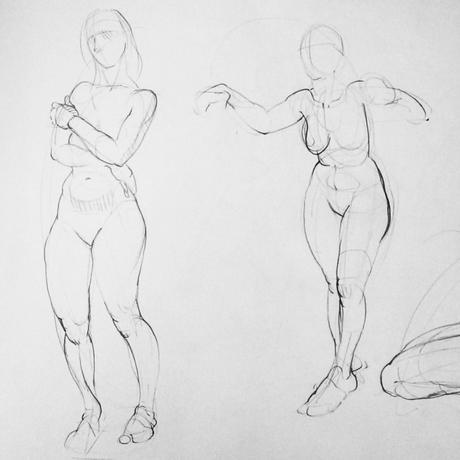

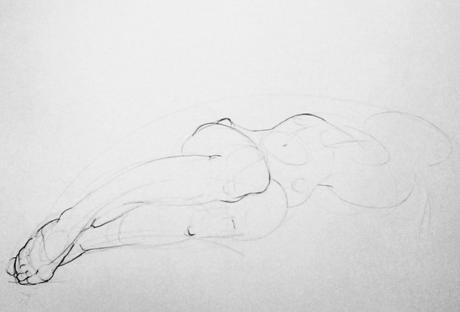

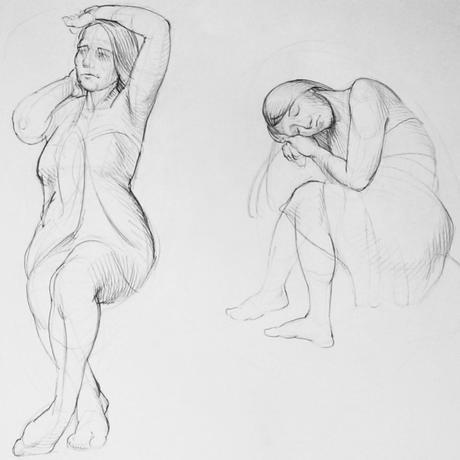

The order we seek to impose is thus not entirely removed from nature. It is rooted in nature, it grows out of a desire to understand nature, and this understanding breeds knowledgeable work. Understanding of muscles and bones brings greater sensitivity to the supple movements of a living, straining body subject to forces. An artist can grow ever more attuned to motion and action, and can make quicker and more economical decisions of how to represent this, favouring eloquent overlaps of tendons here, underlining a weight-bearing limb there, gently bringing out a swelling muscle in preference to a less critical bump, wrapping folds of compressed flesh in sympathy with the stoop and twist of the figure. Order does not extinguish the life of nature. On the contrary: it seeks out the essential life-breathing elements, it searches for the harmony between them, it emphasises unity that would otherwise be lost in the cacophony of overstimulating nature, it reconstructs the world according to highly attentive hierarchies (form over tone, perhaps, and elegance of line over faithfulness to contours, light secondary to volume, atmosphere over crisp exactitude, grouping of shapes of color rather than fidelity to the infinitude of colour). These choices are wherein the art lies. An artist contemplates the limitless world, re-forms it and returns it to us in a more pleasing arrangement.

This is not to say that there is one mold of beauty, for each artist structures her work according to a different system. And not only that, but we each grapple with the time in which we live. Baudelaire (1972: 403) writes of the two halves of art. One is ‘the eternal and the immovable,’ an antiquity alive and present in every age, but this eternal element does not give itself up so freely, and it is this that the artist must distill from the world. It is embedded in every present, and so in each age it takes on a different guise, it cloaks itself in ‘the transient, the fleeting, the contingent’—this is the other half of art (Baudelaire 1972: 403). The real artist, then, ought not renounce her time; she is tasked with extracting from it ‘the poetry that resides in its historical envelope, to distill the eternal from the transitory’ (Baudelaire 1972: 402).

And what precedes such skill is a certain penetrating type of mind. One must, from one’s earliest childhood, be ruthlessly critical. ‘For a poet not to have a critic within him is impossible,’ states Baudelaire (1972: 340), pitying poets dependent solely on instinct. For our ability to improve depends on our selectivity, on our Urteilskraft, on our powers of judgment. Our eye is not easily satisfied, not out of misanthropy but because one taste of something grand has forever raised our standards. We know what is within human reach, and cannot be content with less. We must be ‘poet and critic rolled into one’ (Baudelaire 1972: 340), or we will fail to make a true estimate of our own work, and fail to discover how to amend it.

If there is one thing Baudelaire has really opened my eyes to, it is this: we must not hold back. While our private critiques have bolstered our position, honed our work and sharpened our faculties, we have worked long and hard enough to stand firmly and speak confidently and clearly. And vigorously. What we say might sting, it might win us enemies, it might ring with insult, we might (like Edgar Allan Poe) become known for ‘a hundred other passages where mockery rains down, thick as shot and shell, and yet remains nonchalant and haughty’ (Baudelaire, 1972: 191). But the strength of our insights demand equally forceful delivery. Baudelaire (1972: 51) spurs us on:

‘Once armed with a reliable criterion, drawn from nature, the critic must do his duty with passion; for critic though he may be, he is a man nonetheless, and passion draws men of like temperaments together and raises reason to new heights.’

So my unapologetic intellectual compatriots subject the world to all manner of analysis, inspect it, dissect it, meditate upon it. They put it back together with fearful insight and dexterity. They bolster their cloudy intuitions with concepts they can name. And, when the occasion demands, they rain down their judgements with precision and conviction. Though mountains and oceans separate us, the common threads of our thoughts stretch like glittering webs across the world, fine but strong, and everywhere we rest we plant the seeds of our ideas. We teach, we challenge, we initiate discussion, we loan books, we drop our words, we work, and small ripples begin to spread across the world.

Baudelaire, Charles-Pierre. 1972 [1842-1860]. Selected writings on art and artists. Trans. P. E. Charvet. Penguin: Harmondsworth, England.

In order of appearance in my orbit:

Thoughtful Wander

Conrad Ohnuki

An Island in Theoryspace

R W Daffurn

Scott Breton

lpql.net