I’ll give them a chance that they didn’t give me. They will get a legal trial in a legal courtroom. They will have a legal judge and a legal defense. They will get a legal sentence and a legal death.

The 1930s arguably represent the true golden age of Hollywood. Cinema had emerged from its infancy and stood virtually unchallenged as the premier entertainment medium. The decade conjures up a host of cinematic images: the musicals of Busby Berkeley and Astaire & Rogers, the Gothic nightmares of James Whale, the screwball comedies and the sophistication of Lubitsch, the swashbucklers of Curtiz & Flynn, and so on. But there was something else there too, something that began to drift in from Europe, gaining momentum as the decade wore on and the ranks of the refugees swelled. They brought with them a darker sensibility, partly rooted in German expressionism, and partly a result of their experiences on a continent slowly sliding into political and social turmoil. The seeds of what would grow into film noir were being planted during these years and, despite only the vaguest shoots being visible at that stage, would finally come to full fruition in the 40s. There can be little doubt that the films of Fritz Lang were a major influence on the growth of this movement, and his first feature in the US, Fury (1936), points the way towards what was to come. However this is no film noir; instead it’s a powerful piece of social commentary, a pitiless probing of the darker and less savory aspects of human nature and, ultimately, a classic morality tale.

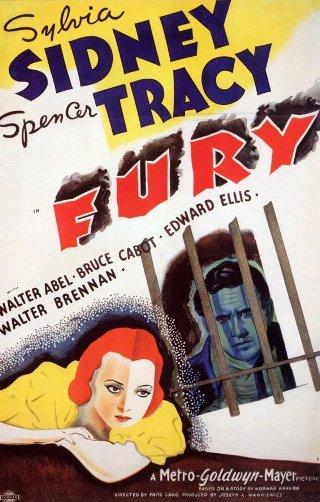

The story concerns an ordinary guy, a guy named Joe. In this case it’s Joe Wilson (Spencer Tracy), a man struggling to get along during The Depression. Times may be tough but Joe isn’t without hopes and dreams, mainly centered on his fiancée Katherine (Sylvia Sidney). Joe and Katherine are in love and naturally want to marry, but that takes money. The film opens with their last moments together, strolling along the city sidewalks and musing about their future as they gaze at the unattainable luxuries in the store windows. Joe is sending Katherine west with a view to joining her and settling down once he has made enough money. Time passes, Katherine pines, and Joe and his brothers make enough from their gas station for him to realize his dream. There’s optimism in the air as Joe sets out on the long drive west and Katherine makes plans for his arrival. Yet all this comes to an abrupt end as Joe is flagged down by a slow-witted, shotgun-wielding deputy (Walter Brennan) from a hick town. It’s at this point that the Kafkaesque nightmare that will ultimately draw in all the characters begins to develop. It turns out there’s been a kidnapping and Joe, as a stranger unable to give a satisfactory account of his movements, is pulled in for questioning as a suspect. There’s only the flimsiest of circumstantial evidence but he’s held until the DA an arrive. However, the gossipy mentality of the small town soon takes over, and the Chinese whispers that ensue have a snowball effect that sees the local citizenry gradually transformed into an unreasoning and rampaging mob. First they lay siege to the jail, then storm it, set it ablaze and finally dynamite what remains. All the while Joe, an innocent man, is trapped inside and growing increasingly panicked. With the building reduced to rubble, it looks as though Joe has perished. The effects are immediate on all concerned – Kathrine, who arrived just in time to witness the final moments, suffers an emotional breakdown, Joe’s brothers are angry and devastated, while the townsfolk begin to feel the first pangs of collective guilt. However, there’s a sting in the tail. Joe survived the conflagration but has physical and, more importantly, psychological scars that are deep rooted. Stripped of his former sense of fair play, he and his brothers set in motion a plan to achieve what he sees as poetic justice.

The fury of the title can be interpreted on two levels, that of the baying mob outside the jail and also that of the man they think they have burnt alive. In both cases, Fritz Lang captured the build-up to and subsequent manifestation of this fury perfectly. The gradual spread of tittle-tattle among the townsfolk is treated in an almost comical fashion at first – the shots of chattering ladies intercut with images of cackling hens – before taking on an ever more menacing character. It all culminates in the wonderfully realized assault on the jail by the frenzied mob. Lang uses montage and lighting to great effect here, cutting rapidly between the faces of the citizens, joyously looking on with an almost religious fervor, and the alternately despairing and stricken features of Joe and Katherine. In this way Lang provokes a combination of horror, pity and moral outrage in the viewer. What we have witnessed is a great injustice, a perversion of the ideals of civilized society. It’s natural therefore to empathize with Joe and the gut reaction is to take pleasure in seeing this victim turn persecutor. However, the film is a critique of the veneer of respectability and civilization that we adopt both as individuals and as a society. As such, Lang does not take us down a morally bankrupt route, choosing instead to focus on the opportunity for personal and collective redemption. In the end the film’s message is that conscience is the real victor, punishing the guilty more effectively than any court of law and hauling a fundamentally decent man back from the brink at the eleventh hour. Again, Lang uses visuals as much as words to make his point, showing how Joe has cut himself off from humanity and the mental anguish that such actions must inevitably arouse. He cuts a poignant figure as Lang shows him alone and bitter, haunted by the voices in his mind and the images of the condemned which float in and out of his consciousness.

Beyond this the film also has some salient points to make about of the role of the law and ultimately affirms the notion of its being one of our fundamental social pillars. However, Lang first takes its weaknesses to task. The fragility of the law is demonstrated by the way the corrupt tendencies of politicians is instrumental in allowing the situation to spiral out of control in the first place. It is also implied, in the disgruntled and disparaging way the citizens of the town speak about the machinations and trickery of lawyers, that the faith of the ordinary man in the legal system has been shaken to such an extent that respect for the law itself is threatened. As is so often the case, it takes the dispassionate eye of the outsider, the immigrant Lang, to draw attention to both the flaws and strengths inherent in the system. Indeed, the point is reinforced early on when one of the minor characters, an immigrant barber, corrects a local on his misunderstanding of the terms of the constitution – his knowledge and respect for the document arising from his being obliged to learn its contents.

If one were to make a list of the greatest screen actors of all time, then Spencer Tracy would surely have to figure high up. Personally, I reckon there’s a case to be made for placing him right at the top. He was probably the greatest exponent of naturalism on screen, rarely, if ever, allowing the audience to catch him acting. As a result, Tracy brought an earnest believability to the varied roles he took on over the years. As he aged he attained something of a statesmanlike quality, becoming the very epitome of the best elements of the American character. Still, even as a younger man, he had that air of honesty and plainness about him, tempered somewhat by an underlying sense of implacability. In brief, the lead in Fury was an ideal role for Tracy, drawing on both sides of his character. He dominates the movie from beginning to end and takes the transition from down to earth guy to hate-fueled avenger smoothly in his stride. And it’s that transition that lends the film so much of its power; the progression from humble amiability through bewildered terror, and then cruel vindictiveness. His reappearance in the aftermath of the jail burning, like some kind of malignant resurrection, is a shocking moment. Not only has he become hard and driven, but there’s a different cast to his whole physical appearance – not some prosthetic alteration but a subtle shift in posture and body language.

Despite Tracy’s powerhouse performance, top billing in Fury went to Sylvia Sidney. Of course Sidney was a big star at the time, making movies for Lang, Hitchcock and Wyler before seeing her career take a downturn. While she doesn’t make the same impression as Tracy, her role is vital to the development of the story and it’s her influence that keeps her man from going over the edge. Sidney’s greatest asset was her wonderfully expressive features, especially those huge eyes. Lang made good use of this by employing frequent close-ups of her, notably as she looks on in horror at the actions of the mob and then later when a shattering realization dawns upon her. The supporting cast is full of memorable turns from a range of familiar faces. I think Bruce Cabot, Walter Brennan, Edward Ellis and Walter Abel all deserve particular attention though – they all make significant contributions as the loud-mouthed rabble-rouser, the gormless deputy, the sour but conflicted sheriff and the determined DA respectively.

Fury came out on DVD some years ago via Warner Brothers, and it’s very well presented on disc. There is a bit of age related damage on view, but the film looks remarkably fine for its vintage. Lang’s movies were always visual treats and the lighting and use of shadows and contrast were particularly important features. The Warner Brothers DVD represents this aspect very well indeed and viewing the movie is a pleasure. The extra features consist of the theatrical trailer and a commentary track by Peter Bogdanovich that includes excerpts from an interview with Fritz Lang. Although Fury is now over 75 years old, the points it makes about society, the law and human nature remain relevant today. That type of timeless quality is a large part of what makes it a classic, but it’s not the whole story. Lang’s striking imagery and Tracy’s unaffected performance are major factors here too. This is one of Lang’s major works, a compelling tale that is emotionally absorbing and also engages the intellect. Definitely recommended.