Upon reflection, 2013 turns out to have been a most argumentative year.

With each season, the Public’s attention shifted between debates over gun control, health care policy, civil unions, and drug legislation. In other circles, disputes raged over the priority of environmental issues, the relationship of science to religion, the morality of popular entertainment and technology, and the proper public place of worldviews like Islam. And in the Internet age, where projecting (or projectile vomiting) our opinions into the world is as easy as pushing a few buttons, we love to do precisely that.

Electricity, indoor plumbing, Social Security (well…): it is always easier to take something for granted when its pervasiveness seems immutable. And discourse is approaching that threshold. The ease with which we speak has led to us forgetting how to do so properly. In person (or “IRL”) conversations and extemporaneous speeches are arts in their death-throes as even our role models are slaves to the Teleprompter-God.

And logic has been a front-line casualty.

Logic: the science of reasoning – rules of thinking that we cannot escape, no matter how hard we try. Aristotle didn’t invent it, but simply codified and described the structure that he recognized in every thinking person’s rationality. And yet, at some point, we exchanged propositions for opinions as our intellectual currency, as if that would shield us from the expectations of logical rigor. Now we sit comfortably in the lie that our beliefs do not need foundations – “that’s just my humble (yeah, right) opinion and I’m entitled to it.”

Indeed, but that does not make your opinion – or at least the way you are presenting your opinion – worthwhile. Sometimes your opinion is not even sensible; even worse, occasionally, your opinion is not even coherent.

And that does not make for good conversation.

Fallacious reasoning – faulty logic – is on the rise. As our ability to grapple with ideas has waned, the strength of a variety of informal logical fallacies has grown. These missteps in thinking come not from the structure of an argument (as in a formal fallacy), but typically stem from a confusion in the words or the method used to present an idea. You don’t need to know the technical details of what makes an argument valid or sound in order to understand the problems with the following examples – just an open mind and a sense of humor.

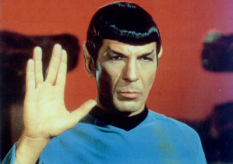

Because logic is not an enemy, indeed it is inescapable element of the thoughtful life. As a most logical Commander once observed, “Logic, logic, logic. Logic is the beginning of wisdom, Valeris, not the end.” May it also be a part of the beginning of our New Year.

And may you live long and prosper in 2014.

From the Fallacious: Twelve Informal Fallacies

Appeal to Authority

Although I am familiar with the nature of an argument, I find myself so impressed by a charismatic third party to our conversation that I will relinquish my opportunity to rebut your position by simply deferring to a statement that he or she has made, regardless of either its applicability or their legitimacy as an authority on the matter under discussion. Bonus points to me if my citation is uncritically accepted as noteworthy, despite the person’s irrelevant expertise.

Example: “That race-car driver said that this toothpaste heals cavities!”

Argumentum Ad Hominem (“Argument to the Man/Person”)

I have an opinion that contradicts your stated opinion. I do not wish to expend the time or energy to compare the two propositions to both each other and reality, therefore I will attempt to remove your opinion from the playing field of our conversation by rhetorically removing your right to hold respectable opinions. If this fails, I shall repeat myself with increasing volume until we tire of the game and agree to end our discussion without actually discussing anything.

Example: “Well, the President is just an idiot, so he’s obviously wrong.”

Argumentum Ad Baculum (“Argument to the Stick”)

Despite my ability to calmly listen to your arguments and rationally respond with points of my own, I will forego that method of thoughtful discourse and degenerate into an oratorical caveman whose only method of expressing disagreement is to make either implicit or explicit threats upon your person. Nevermind that my aggression is utterly inconsequential to the truth value of your statement: my goal is now to simply scare you away from our conversation.

Example: “If you’re right, then my large friend here might feel the need to have some words with you in that dark alleyway over there.”

Burden of Proof

While I recognize that our conversation is equally weighted, I shall spend my time stubbornly and repetitively demanding that you have not proven your side of the debate beyond a shadow of a doubt instead of attempting to meet the burden of proof necessarily garnered by my own position. Despite the absence of any offered positive evidence for my proposition, I shall nevertheless declare victory for myself thanks to my perception of your inadequacies. The fact that I make this proclamation from atop a mountain of only my own complaints (as opposed to arguments) is immaterial.

Example: “You cannot prove with certainty that God exists, therefore I am certain that he does not exist.”

Equivocation

Whether or not English is my primary language, I am well aware of the polysemous nature of much English vocabulary. Nevertheless, I shall ignore potential ambiguities in my argument’s word choice and barrel on towards my conclusion, ignoring any shift in what my lexical signs may signify. When I use the same word more than once, I shall obstinately demand that its definition never changes, even when the context of each sentence indicates precisely the opposite.

Example: “Moldy bread is better than nothing; nothing is better than fried chicken; therefore, moldy bread is better than fried chicken.”

False Dichotomy or False Dilemma

Regardless of the complexities surrounding the issue at hand, I shall attempt to simplify our conversation (in my favor, I might add), by dissolving every possible solution into two simple choices, probably with my preferred option as obviously more tasteful than the other. Nevermind that a genuine dichotomy consists of a proposition and that proposition’s direct negation; I am confident in my ignorance that you will be forced to concede your misrepresented and over-simplified idea.

Example: “Either God arbitrarily defines what is Good or He uses some larger standard of Goodness that makes His decrees irrelevant.”

The Genetic Fallacy

Whereas your argument might be sound, I disapprove of (or believe that someone else will disapprove of) its source and will forego standard measurements of validity and soundness for the sake of denigrating your proposition’s origin point on the basis of its perceived lack of intelligence, morality, or fitness to our situation. With all my energy focused on insulting the theoretical birthplace of your idea, I may not have it in me to deal with your actual argument, but I hope that we both can see past that deficiency.

Example: “You only think that abortion is wrong because your parents raised you to think that!”

Loaded Question

Despite my interrogative sentence, I am not actually seeking information about you or your ideas, but am merely looking for an opportunity to contribute to your eventual rhetorical downfall via an insulting or misleading implication stemming from the ambiguity of your limited yes/no response.

Example: “How long has it been since you last booted black-tar heroin?”

Petitio Principii (“Begging the Question” or “Assuming the Initial Point”)

I understand that I need to prove the point I am defending, but the truth of my position is so obvious to me that I will simply assume its veracity from the beginning as a premise for my argument. I will probably change the wording of my proposition between premise and conclusion to shield my trickery, but the concept involved will be identical. This makes my job far simply: it is always easier to assert than to argue.

Example: “The Bible is true because the Bible says that the Bible is true.”

The Post-Dated Check

I fully recognize the lack of evidence that could positively confirm my position at the present time, but I remain hopeful that such proof is forthcoming. I am so confident in the eventual success of researchers on this topic that I will go ahead and declare victory for myself now, despite the utter paucity of available information with which I could substantiate my claim today.

Example: “We may not yet scientifically understand how something could come from nothing, but give us more time – we’re still working on that.”

Straw Man

I would like to disagree with your position, but find myself incapable of doing so. Consequently, I shall instead describe a position that seems vaguely similar to yours, but is far easier to refute. I shall pride myself on my cleverness and perhaps even declare victory, all the while praying that my irrelevance goes unnoticed.

Example: “God obviously doesn’t exist because the Bible makes Him look awfully mean. How could the God who commanded the Israelites to do that actually exist?”

Tu Quoque (“You Too!”)

I feel that the best way to respond to your criticism of my position is by ignoring your concern and deflecting your accusation back in your direction, regardless of how relevant your complaint is to my argument or irrelevant it is to yours.

Example: “Is it true that you were at the brothel last night?” “Did you see me there?”

photo credit: unknown via photopin

Tags: 2013, 2014, Argument, Commander Spock, Logic, Logical Fallacies, New Year, Star Trek