Music to accompany article: St Matthew Passion: Erbarme dich, mein Gott by J.S. Bach

Friedrich Nietzsche died on 25 August 1900, at the dawn of new era and a new consciousness. Torn between the need for veneration and the need for independence of the soul, this man of profoundly religious nature became one of God’s most notorious assassins. Given his posthumous association with the Nazis, has he not taken the guilt, rather than the punishment?

How to Take the Guilt not the Punishment

“Devise the love that bears not only all punishment but also the guilt!”

Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Of the Adder’s Bite

Paradox permeates Nietzsche’s thought and his entire being. To understand the contradictoriness of Nietzsche the philosopher, as well as Nietzsche the man, one must acknowledge coincidentia oppositorum, the coincidence of opposites. This concept originated in Heraclitus (much admired by Nietzsche), who believed that all existing things were characterised by pairs of opposing properties. As these strive towards unity, “the path up and down is one and the same”. The battle of the opposites, fueled by life-long mood fluctuations, became a turbulent undercurrent in Nietzsche’s philosophy. The constant tension and energy of this conflict were a source of inspiration and creativity for him; the strife led to “new and more powerful births”. The Apollonian and the Dionysian became the most famous of his binary concepts, but other Heraclitean ideas are even more provocative: “pain and pleasure are not opposites”, “health and sickness are not essentially different”, “scorners are only hidden admirers”, “truth is a lie according to fixed convention”…

As a young man, Nietzsche – then an exultant believer – wrote a poem entitled “To the Unknown God”:

I lift up my hands to you in loneliness―

you, to whom I flee,

to whom in the deepest depth of my heart

I have solemnly consecrated altars...

Torn between faith and truth, between reason and unreason, between veneration and rage, many years later he exclaimed: “Whoever wants to be a Christian should tear the eyes out of his reason”. He went on to launch a devastating attack on religion.

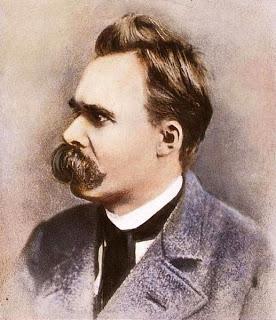

Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich NietzscheFor Nietzsche, genuine love is irreconcilable with evoking guilt. In his book On the Genealogy of Morality, following his customary ‘via etymologica’, he regards guilt primarily as a form of debt (in German die Schuld means both), hence the act of giving must never overwhelm the receiver. In The Antichrist, Nietzsche portrays Jesus as a rebel who stood up against the Jewish establishment, and who got what he deserved. He died for his guilt, and at other times (and in another place!) he would have been sent to Siberia as a political criminal. Nietzsche’s rejection of the Christian doctrine was, above all, a rejection of Christ’s sacrifice that burdened humanity with a non-repayable debt, with a ‘bad conscience’. By contrast, “the [ancient] gods served to justify man to a certain degree, even if he were in the wrong, they served as causes of evil – they did not, at that time, take the punishment on themselves, but rather, as is nobler, the guilt” (On the Genealogy of Morality). Consequently, “A god come to earth ought to do nothing whatever but wrong; to take upon oneself not the punishment but the guilt – only that would be godlike” (Ecce Homo). In Nietzsche’s moral universe, a truly loving God would have to be Satan!

According to Christian teachings, we are ‘redeemed’ from our prior condition of ‘slavery to sin’ by Christ’s death on the cross. Nietzsche vehemently rejected the presupposed sinfulness and wretchedness of our existence, and the eternal, non-repayable debt to the Redeemer. The Christian doctrine of sin – by engendering feelings of impotence, guilt and damnation – denigrated real life on earth to being an ante-chamber to some other-worldly existence. The disparagement of passions, particularly the sexual ones, lowered the believer’s general state of vitality; in short – Christianity became an anti-life religion.

Nietzsche’s name has often been associated with Nazi ideology. This is much owing to his Machiavellian sister, Elisabeth, who invited Hitler to her brother’s shrine in Weimar in 1934 and made an offering of his philosophy. Ideas such as Übermensch and The Will to Power had an instantaneous appeal for the führer. But did not Nietzsche court his destiny?

“I know my fate. One day there will be associated with my name the recollection of something horrific — a crisis like no other before on earth, of the profoundest collision of conscience, of a decision evoked against everything that until then had been believed in, demanded, sanctified. I am not a man, I am dynamite.”This prescient passage comes from Ecce Homo, Nietzsche’s penultimate book and self-styled autobiography. The words originate from Pontius Pilate who presented Jesus Christ, bound and crowned with thorns, to a hostile crowd, shortly before his Crucifixion. While on the verge of a total mental eclipse, Nietzsche signed several of his letters “The Crucified”, and Karl Jaspers believed that he was in rivalry with Christ, unconsciously trying to supersede him. By taking upon himself not the punishment but the guilt, Nietzsche may have become Milton’s Lucifer who would rather “reign in Hell than serve in Heaven”. And perhaps this was the essence of Nietzsche’s Antichrist, a contrapuntal figure par excellence.

In his last book, Dithyrambs of Dionysus, Nietzsche included “Ariadne’s Lament”, a poem full of pain and longing:

Who still warms me, who still loves me?

Offer me hot hands! Offer me coal-warmers for the heart! [...] He is gone! He himself has fled, My last companion, My great enemy, My unknown, My Hangman-god!― ―No! Come back,

With all your torments!

Oh come back

To the last of all solitaries!

All the streams of my tears

Run their course to you!

And the last flame of my heart―

It burns up to you!

Oh come back,

My unknown God! My pain! My last ―

happiness!...