For the past three years, I’ve been dabbling in short fiction here and there, in between writing novels and working. I used to love writing short stories, even going as far back as to middle school. Now, I prefer the longer form of novel writing, but I still like to practice the short form.

For the past three years, I’ve been dabbling in short fiction here and there, in between writing novels and working. I used to love writing short stories, even going as far back as to middle school. Now, I prefer the longer form of novel writing, but I still like to practice the short form.

The short story requires writers to tell a quick story—one where you get to know the subject and characters right away—in a minimum amount of words. This is a challenge, and it’s not easy to do.

I’m sharing today a WIP – a WORK IN PROGRESS. Part One is almost done, though not refined. I still have to write Part Two, and it’s taking me some time because I have to do a little World War II research on dates and things.

Anyway, as I’m not shy to share my process and love for writing, I thought I’d post what I have so far. Sometimes I think I was born in the wrong era. I love the time period from the early 1900s up until the 1950s. I love big band music, that fashion from that era, and stories of World War II (and World War I). For Inn Significant, I had to research the Great Depression, and I enjoyed learning more about that time period so I could write Nana’s journals. So you’ll see, I have more work to do here.

But what the heck, I’ll share what I have so far. This will eventually go into my short story collection called The Postcard and Other Short Stories & Poetry. I hope to have that out sometime this year.

War, Books and Ladybugs (working title)

A Short Story Draft by Stephanie Verni | copyright March 2018

The day her father left, Sophie cried. She stood at the end of the dirt path, her mother inside the house refusing to see him off, too resentful of what it was doing to her family to say goodbye. As the car destined for town that would have all the men board a bus that would take them to Fort Bragg arrived, her father gave a short wave and nod to her, and she waved back, fighting back the tears as hard as she could as he hoisted his sack into the vehicle and leaned inside. That’s when the tears began to flow. At twelve, Sophie was well aware of the dangers her father could face and the possibility that he may never return home safely. Plenty of her friends back home had lost their own fathers months earlier. Because of the stories she had heard and the sadness she had seen on the faces of people she knew well, she could understand her mother’s apprehension, worry, and desperation at the thought of being left to fend for herself and her child in this world.

The other end of the dirt path sat at the stone walkway to Sophie’s grandmother’s house, a grand white home with a sprawling front porch and wooden front steps perched in the lower mountains of Lynchburg. Her grandmother had taken them in while her father fought for the liberties of others. They had given up their own home four hours away up north, the one where they had lived for years, the one Sophie had called home, and the one where she had first believed in Lady Luck.

When her father had told her the news that he was called up and headed to Fort Bragg, he relayed the news that Sophie and her mother would be moving and living with Grandma. They sat on their porch together back in Maryland, as he tried desperately to comfort her.

“It’s my duty,” he had said, trying to rationalize the idea of war and tighting to a young girl. “We have to protect what we believe is right.”

Sophie looked at him with her big blue eyes, her hair knotted from playing outside, her freckles more apparent because she was in the sun so often. She swallowed hard, knowing the decision was already made and there was no turning back.

As she reached to give her father a hug, a ladybug landed on Sophie’s shoulder, then another one on her thigh. Her dad looked at them and smiled.

“Well, Sophie-Belle, looks like you just brought us some luck.”

“There are so many more this year,” Sophie said, looking at the small red and black beetle her dad had collected into the palm of his hand.

“Perhaps I won’t be gone for long after all,” her father said.

She remembered that day now, listening to the happy sounds of birds chirping in early spring, as she walked back up to the house remembering how she said goodbye to her father right here, the dirt flying off the tires of the car, as her dad disappeared down the road, off to protect his family in a different way.

She also remembered opening the door to the house and seeing her mother standing near the window staring straight ahead, a handkerchief in her hand. It was then that Sophie began to worry, and had subsequently remained worried for two full years.

*

Her grandmother did her best to keep them all from dwelling on what was happening in Europe. In fact, it was her grandmother who turned off the WLVA radio broadcast one night, they’d listen to report after report and become more depressed for doing so. It had become increasingly more difficult to listen to reports about the war and Hitler and lives lost. Her hands were poised on her hips, and she uttered the words, “No more.” They all looked at her standing there in her apron, her hair tied tightly in a bun on the top of her head, the lines on her face looking just a bit deeper than they did months ago.

“I have an idea,” she said.

She told Sophie, Timothy, and Sophie’s mother to all pile into the car and snatched the keys to her vehicle. The smell of autumn was in the air, despite that it was only September. The smell of the outdoors awakened Sophie’s senses. It was dusk, and her Grandmother put the keys into the ignition and began the drive down the roads lit only by the headlights and the early moonlight.

“Where are we going, Grandma?” Sophie asked, still unsure as to what her grandmother’s great idea might be.

“You will see soon,” she said.

After several minutes, Sophie could see buildings take form in front of her, and she knew they had reached downtown Lynchburg. What was going on this evening, she wondered. Where was her grandmother taking them at this hour?

When they rounded the corner, Sophie could see a grand building with a rotunda roof rising up in front of them. It was one of Lynchburg’s landmarks, and Sophie knew it immediately. Her grandmother—very much in control of her red Packard station wagon, a veritable renegade whom Sophie always admired for her positive attitude and spunk—pulled over and parked on the street in front of the Jones Memorial Library.

“We are going to the Library, Mother?” Sophie’s mother said aloud in an incredulous tone.

“We are.”

“But what on Earth for?”

“To take our minds off the news…the war. Let me show you what’s inside.”

Sophie’s grandmother had been working for many years at the library. She was one of three main librarians there.

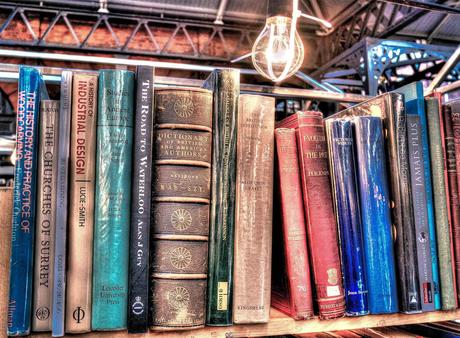

After struggling to get the key in the door as the library had been closed for a couple of hours, her grandmother finally gained entrance. Sophie loved the smell of the place—the smell of hardback covers and a mustiness that she couldn’t quite describe. Sophie’s grandmother turned on the dim lights, and the four of them stood in the middle and looked around. Libraries are typically a quiet place, but tonight, this one felt cathartic. There was something peaceful about it.

“Come to the back storage room,” her grandmother said, not in a whisper voice, but rather a regular talking voice. “I want to show you something.”

She opened the door to the storage room, Sophie right behind her, and they looked. There were hundreds of books scattered all over the place—on the floor, on the tables, and stacked up on chairs.

“What is all this?” Sophie asked.

“These are the books that we can no longer use,” her grandmother said. “They are either too old, falling apart, or we have so many extra copies we don’t know what to do with them. The head librarian gave us permission to get what we want first, and then we will have a little library sale and make a little extra money. So, as you can see, there are many. I will make a donation to the library, and we will have first choice, as I was approved to do so. I suggest we all pick three or four books to take home. I even cleared off a couple of shelves so we can have a begin to create our own home library. Or, we can just borrow from this library. But I want us reading and sharing—I’ve always wanted to do that. Does that sound like fun? Does it sound like something we could do to take our minds off the news reports?”

Sophie watched her mother intently, waiting to see her reply. Her mother was one to keep everything locked down deep inside and not share anything—not her feelings, her concerns, her worry, or her desire to be distracted by something. Sophie kept a keen eye on her to see how she would respond to her mother’s idea.

“I think it’s an ingenious idea, Mother,” Sophie’s mother said aloud to all of them. “I like it very much. I’d like to get lost in a good book and escape. And I’d like to get Sophie reading more.”

“Then it’s settled. If you want to purchase a few books, let’s do it. If you want to borrow some books, let’s do it. So here are the rules: we each pick three or four books we like to begin and that will make 12 books for our initial run at this thing. We can share what we are reading and how we like the books when we have dinner at night. Then, if we like the stories, we can exchange them and talk about them. But let’s sink our teeth into something other than these war stories that leave us depressed.”

And so they began to shuffle through the abundance of books in the back room. Sophie likened it to Christmas morning when they would open their presents, although there had been few the last few years. Books made a wonderful companion to the long winter’s nights that would lay before them as the weather would soon be changing, and so Sophie plowed right in, searching for just the right ones to start off with on this new reading adventure. Sophie found a couple of Nancy Drew mysteries and The Hundred Dresses; her mother decided upon Dale Carnegie’s How to Stop Worrying and Start Living and A Tree Grows in Brooklyn; her grandmother scooped up The Portable Dorothy Parker and Agatha Christie’s Death Comes As The End; and her uncle spotted The Fountainhead and The Ministry of Fear.

Sophie could feel her spirits lifting as she perused the books. She liked reading, but she did not read enough, despite that her grandmother worked at the library. She was intrigued by the idea of reading and sharing; it gave her something to look forward to. Maybe she would read them all. She was turning into a young lady now, and perhaps she could attempt to read more sophisticated literature.

As they finished selecting their books, Sophie heard her mother say, “Do you think I could work here, too? Do they need any extra help?”

Sophie could not hear her grandmother’s reply, but she understood why her mother was asking. The library was certainly a place where one could get lost and forget all her problems.

They made their ride home in silence, each one of them pensive, thinking of their books, each one doing his or her best not to mention the word ‘war.’

*

When Sophie’s father’s letter finally arrived, it looked worn and beaten, as if it had been through a few tough passages itself. It was a Saturday morning, and the sun was rising high in the crisp November air. Sophie had read two books so far in addition to managing her own schoolwork and chores around the house. Her grandmother’s property needed a lot of upkeep, and with her grandmother working at the Library, in addition to her mother taking on a job at a factory in town, it was more important than ever for Sophie to do her part at home while others did their part elsewhere. And her uncle helped as he could, and had taken on the role of writing to soldiers as he could.

“Grandma,” Sophie said, as she ran into the kitchen, “it’s a letter from Dad.”

“Well, then you must open it and read it to me,” Grandma said, relieved that there was at least a letter in their hands.

Dearest Sophie, Addie, Mom, and Timothy,

I am writing to you from a small town in France, though I don’t think we’ll be here long enough for it to amount to anything firm and I’m not supposed to disclose our whereabouts. As you are probably getting reports from the radio, it’s not good here. We have lost a lot of men, and the fighting continues, although something inside of me is hopeful that it will not last much longer. I have heard the men talk of things happening, though I’m not sure when or where or how. Please know that I keep all of you in my heart and when I’m feeling particularly low or sad or overwhelmed by fear, I picture your faces in my head. I’m sorry that this is only the third letter you have received from me, but pen and paper are rare, and when we do find it, we all scribble things and try to get something sent back home because we know you are probably worried sick. It won’t be a long letter, but know that I love you all more than life itself, and that I will fight for us, and that I long to be home to see your smiling faces again. I will dream of hugging you all tightly,

Until then, much love,

John (or Dad)

Sophie sat and scratched her head as she looked out the window, her eyes becoming misty.

“He sounds so sad,” Sophie said.

“He just misses us tremendously,” her grandmother said.

“When he returns, we will have to lift his spirits and get him to join our reading club,” Sophie said.

“I think he’d like that very much,” Grandma said, as she turned her back to Sophie and sniffled. “He always was a good reader.”

*

Sophie’s mother called the meeting to order in the town’s library.

“Well, y’all, it’s the first Friday of the month, and I call this meeting to order,” her mother said, as she stood, trying to get the group that had assembled in order.

“As we have done for the last two months, we will take turns giving a two-minute overview of the book we have each read over the last few weeks. I hope everyone has finished their books.”

As word spread about the Sophie’s family’s reading club, it had quickly grown to a group of twenty. People wanted to join. The library had offered to remain open late one evening every month, as the meeting was to begin promptly at 7 p.m. after the last factory shift had ended.

“Let’s start with you, Mrs. Bates,” Sophie’s mother said, and turned the program over to Mrs. Bates, who stood by the window in the living room, held the book in her hand, and removed the kerchief from her head.

“Good evening, fellow readers,” Mrs. Bates said. “I’m here to tell you about the book I read, which I liked very much indeed and would recommend to you all. It is called Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier, and it’s about a woman who falls in love with a widower who owns a tremendous country estate called Manderlay, but his recent dead wife seems to haunt the place. And then there’s a woman, Mrs. Danvers, the housekeeper, who doesn’t much like the second wife and raised Rebecca and protects her memory. It’s a mystery, and I couldn’t stop reading it. And it’s set in Monte Carlo.” Sophie’s mother wrote the name of the book on the adjacent blackboard and gave it a check, which meant Mrs. Bates liked it.

When Mrs. Bates finished, everyone clapped. And that’s how it went for the better part of forty-five minutes as thirteen of the folks assembled shared what they were reading. Some were new members and this was their first time. Afterwards there was punch served, and Mrs. Conway brought her savory chocolate chip oatmeal cookies; Sophie talked with her friend, Beatrice, as the rest of the bunch mingled.

*

Sophie’s mother was wearing a blue dress and was off to work at the factory that day. Her face seemed brighter than it had been months ago. The job at the factory had helped her mood, that much Sophie could see. Her sense of humor had returned as well, and she said funny things to Sophie all the time.

It was May, and horrible, rainy, wet April was done. Sophie longed for the flowers to bloom and to feel the sunshine on her face, to wade in the river and to be done with school, and to stretch out on the grass on her favorite blanket and read a book.

Sophie’s mother kissed her on the forehead.

“Have a good day today at school, and don’t let that boy pull your hair anymore or I will have to speak to his mother.”

She winked at her daughter because she knew Johnny Doyle liked Sophie, which was why he was trying to get her attention. But Sophie wanted none of it. She was not interested in boys—well, at least not that one.

*************

End Part One.

Part Two Next Week…

*