Author: Marina Valcárcel

Art Historian

In 2004, 50 years after Frida Kahlo's death (Mexico 1907-1954), thousands of her personal belongings and artefacts saw the light of day again. Photographs, diaries, drawings, books ... along with pillboxes of her painkillers, orthopedic corsets, hospital gowns, half-used nail varnishes, combs, a bottle of Shalimar - the perfume she wore to try and camouflage "[her] body's smell of dead dog" - clothes, a Revlon eyebrow pencil and pink silk ribbons for her braided up-do hairstyle. Today, all of these dresses and objects, as if characters in her own life story, have left their home (The Blue House in Coyoacan) for the first time ever, en route to the Victoria & Albert Museum in London for the exhibition Frida Kahlo: Making Her Self Up.

Corset and skirt from Frida Khalo's collection. Photograph from Frida by Ishiuchi (RM Editorial)

It's a story straight out of a Fake News headline. On Frida's death, the painter Diego Rivera, in an attempt to preserve their intimacy as a couple, ordered two rooms in their Blue House home to be sealed with all of possessions and documents locked inside. The moment the little ensuite bathroom adjoining her studio was re-opened and its contents revealed, so too was the message that Frida was transmitting through her clothes. Both Frida and Diego were intense characters, poetically terrible at times and touchingly tender at others. On the centenary of her birth, the press announced the emergence of some 22,105 documents, 5,387 photographs, 168 outfits, 11 corsets, 212 drawings by Diego, 102 by Frida, 3,874 magazines or publications and 2,170 books. These can be found in various compilations, for instance, Frida: Her Photographs and Frida by Ishiuchi (both RM Editorial).

Frida Kahlo's make-up. Photograph from Frida by Ishiuchi (RM Editorial)

The discord in Kahlo's body began when she was just six years old with a bout of polio which left her bed-bound for nine months. Doctors, pain and sedatives made their first appearance in her life. When she recovered, she did so with one atrophied leg and a complex born of being nicknamed "peg-leg" by the neighbourhood children. She, however, enjoyed climbing trees and learned to overcome somewhat but one of her legs remained shorter and thinner than the other. She disguised this by layering pair after pair of thick socks and wearing knee-high boots. From this tender age, she was already beginning to speak through her clothing.

Frida Kahlo's boots. Photograph from Frida by Ishiuchi (RM Editorial)

17th of September 1925: the accident

Frida was 18 that morning she left home with her school books and her boyfriend. “I got on the bus with Alejandro and sat next to the rail with him beside me. A few moments later, the bus crashed into a tram. It was a strange bang, dull rather than violent. The impact sent us flying forward and the rail pierced my body as a sword pierces a bull. A gentleman, seeing my wound bleeding profusely, laid me on a billiard table."

Alejandro described his vision of the incident as: "Frida was left completely naked. Her clothes had been ripped off in the accident. A passenger, no doubt a painter by trade, had got on the bus with a packet of gold-coloured powder. The packet split in half and the gold dust went swirling around her bleeding body." Frida lay there covered with a dew-like sprinkling of gold. The diagnosis: triple fracture to her spinal column, fractured collarbone, fractured third and fourth ribs, dislocated left shoulder, thigh fractured in three places, perforated stomach and vagina, eleven fractures to her right leg, dislocated right foot. The medics of the Red Cross gathered up the pieces of her body under no illusions that she would survive the operating table. Her human capacity to withstand such horrific pain would have seemed impossible to them. As would her indomitable will to live.

On leaving the hospital, her mother settled her in a four-poster bed with a mirror attached above and ordered a custom-made easel. Frida remained locked inside her own world, focused on a mirror the size of a picture portrait. During the day, she read avidly between visits from her schoolmates. Chinese poetry by Li Po, Bergson, Proust, Zola and also articles about the Russian revolution and stamp books by Cranach, Durero, Botticelli and Bronzino. But as night fell, so did the images that devoured her, isolated her and terrified her. “Death dances around me all night long", she wrote to Alejandro.

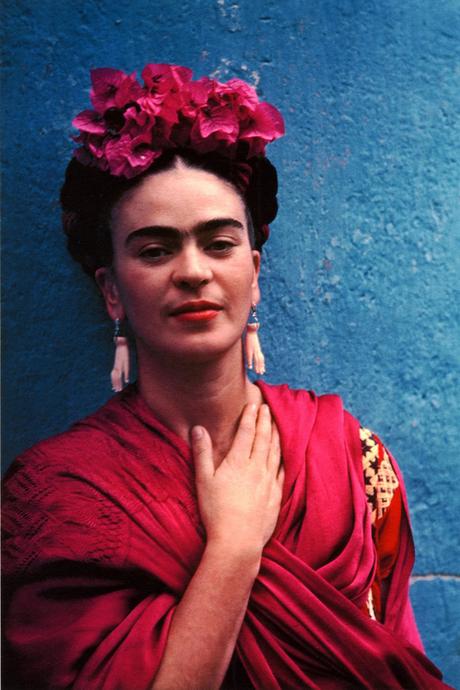

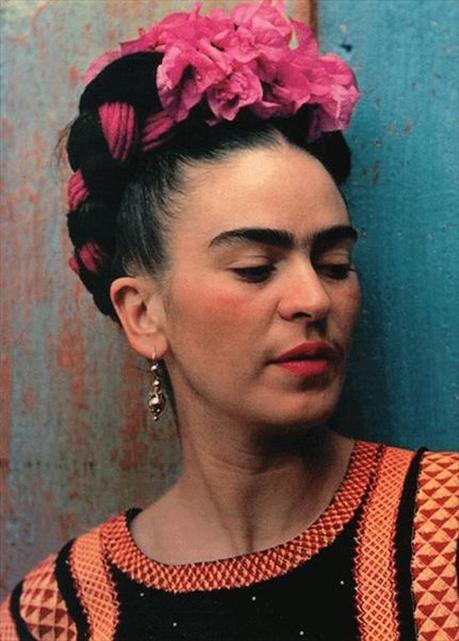

Diego Rivera recalls how Frida first made her appearance in his life: “One day, I was working on frescos at the Ministry Of Education when I heard a young woman's voice shouting up at me saying, Diego, please come down from there. There's something important I have to talk to you about ... and standing below me was a girl of about 18, nice figure, a bit agitated. She was wearing her hair down and she had these thick, dark eyebrows that met in the middle. They looked like the wings of a blackbird." Rivera ~ then 42, nearly 6 foot tall, 16 stone, already married to Lupe Marín and one of the "Three Great" Mexican muralists of that time ~ accepted the role of Frida's boyfriend. Her family commented that it was "the union of an elephant and a dove".

Diego was her God, her father, her son, her "second accident". Every morning, as if in a ritual, Frida would dress herself up like an idol, designing her costume and jewelry so as to hide the wounds on her body. She adorned herself for him as the women of Tehuana did, seeing in their indigenous clothing a political statement and a vindication of her Mexican heritage. Those outfits comprised 3 pieces: the petticoat, the Huilpil (a square-cut blouse that made her look taller) and her updo of braids and flowers which drew the onlooker's gaze upwards to her head and upper torso and away from the lower part of her body.

Frida Kahlo with Diego Rivera

The Blue House

The building that today houses the Frida Kahlo Museum was built by her father 3 years before she was born and painted a bright cobalt blue to ward off evil spirits. It was then extended by Diego and decorated by Frida to resemble a microcosm of tropical vegetation with cacti, orange trees and Aztec idols perched on a small pyramid where a coterie of animals held court, all humanised by their names.

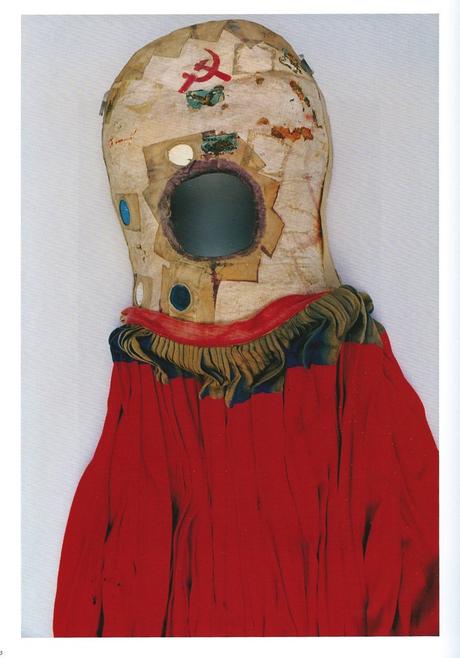

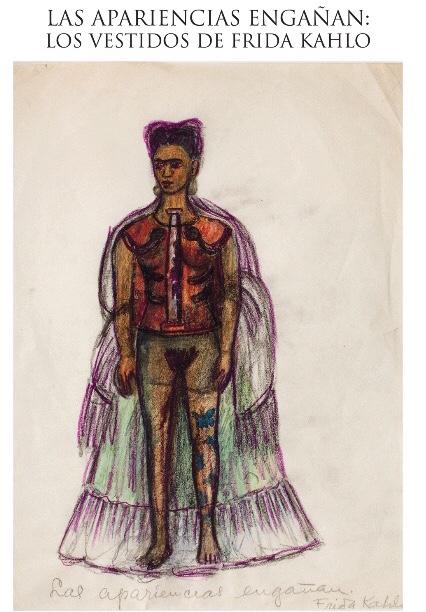

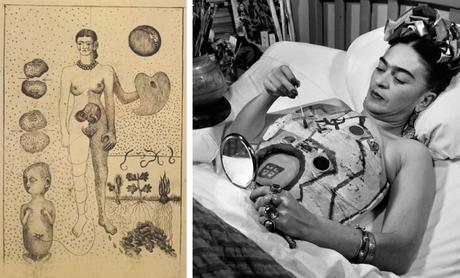

In 2004, one of the most exciting moments at the opening of the sealed rooms was the discovery of a drawing entitled "Appearances can be deceiving". In it, Frida's broken, naked body appears as if X-rayed, with blue butterflies painted over her leg fractures and a slender pillar in place of her spine. She then, in purple pencil, drew a sheer gown over herself leaving her battle-scarred body visible. It is curious in that Kahlo, who would dress in real life with a view to disguising her disabilities, allowed those very disabilities to be viewed under stark scrutiny in this and other paintings.

Poster for the exhibition based on Frida Kahlo's drawing "Appearances can be deceiving", Coyoacan, 2013

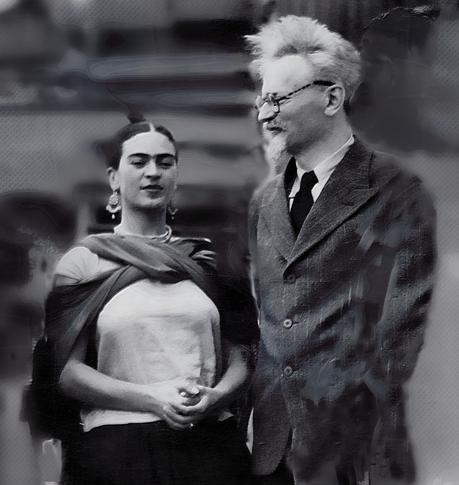

In 1937, Leon Trotsky moves into the Blue House and stays there for two years, making it his revolutionary fortress. It didn't take long for the author of The Permanent Revolution to succumb to the charms of his beautiful hostess. They would speak to each other in English, a language Trotsky's wife Natalia couldn't understand, and Frida would pass him love notes she had hidden in her clothes.

Frida Kahlo with Leon Trotsky

Pablo Picasso, too, would adorn Frida. On a visit to Paris, he gifted her a pair of earrings shaped like hands that dangled and twinkled below her braided hair of bougainvillaea and bows. She was forcing us to look at her face. Her lips, painted bright red, always appeared tightly closed in photographs and paintings alike. She never showed her teeth, hiding the invisible jewels that were her gold incisors and which, for special occasions, she would set with little pink diamonds.

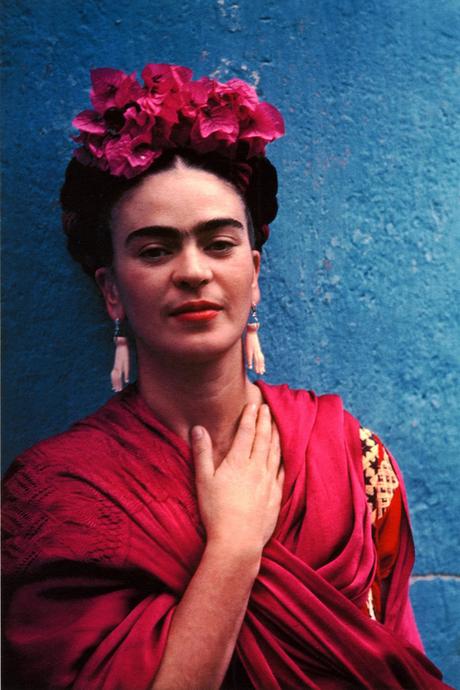

Frida Kahlo wearing the earrings Picasso made for her

Frida Kahlo painting her corsets

“I am disintegration”

In early 1950, Frida was admitted as an in-patient for a year in Mexico City. Diego moved into the room next to hers and the hospital stay became a party: "I always kept my spirits up. I spent a lot of time painting because they kept me dosed up on Demerol. That substance made me happy."

A year before her death, the gallery owner Lola Alvarez Bravo organised an exhibition. It's now April 1953. Diego arranged the transfer of her 4-poster bed into the middle of the space. Frida made her triumphal entrance accompanied by the wail of ambulance sirens. The guests gathered around her as she persevered with the aid of painkillers. She was the embodiment of triumph over pain. Then after this homage came the verdict on her right leg. It would have to be amputated. Frida wrote in her diary: "I am disintegration."

From then on, Frida devoted herself and her time to fine-tuning the new parts of her broken body. Her red boots, the finishing touch to her false leg, she decorated with Chinese embroidery, gold thread and little bells. These are, without doubt, the most enigmatic of all the objects in this exhibition. As are the corsets she had to wear, a stark reminder of her torture. Her relationship with them was one not just of necessity and support but also of rebellion. From then on, we would only ever again see Frida approaching in her wheelchair, preceded by the murmuring jangle of her jewelry.

Meanwhile, death was inching nearer, on tiptoes. She dressed, now, for days and nights in bed painting and this was how she prepared for her departure from life to heaven. She realised she was killing herself. The drugs and alcohol that gave her relief and release were likewise a death sentence. At the age of 47, Frida is cremated. It is said that, on the exit of her remains from the crematorium, Diego swallowed a handful of her ashes.

Frida Kahlo's orthopedic boot. Photograph from Frida by Ishiuchi (RM Editorial)

Frida Kahlo: Making Her Self Up

Victoria and Albert Museum

Cromwell Road, London

Curators: Claire Wilcox and Circe Henestrosa

From 16 June until 4 November 2018

(Translated for the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving - - Alejandra de Argos -