WOLFGANG GRUPP embodies the values of the Mittelstand—the mid-sized firms, often family-owned, that employ 60% of German workers. Permanently tanned and dressed to the nines, he is the third generation in his family to run Trigema, Germany’s largest maker of T-shirts and tennis clothes. He takes pride in the fact that all 1,200 of his employees are in Germany, and all are well-paid. He is grooming his son and daughter, educated at a Swiss boarding school and the London School of Economics, to run the firm with the same sense of social duty.

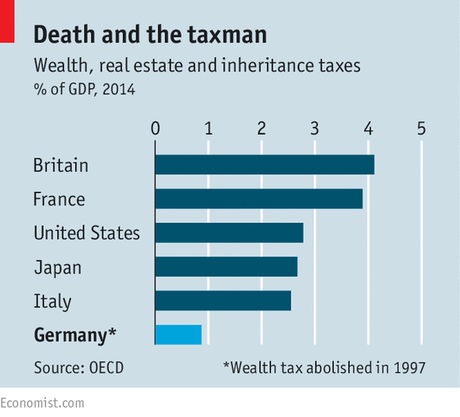

That is why Mr Grupp insists that businesses such as his must be exempt from inheritance tax. People who inherit cash or shares, he argues, can easily spend it. But when his children inherit Trigema, they “can’t start eating the factory”. Hitting such heirs with tax might force many to sell, he says, and then German business would “soon be finished”—especially if the bargain-hunters come from America, that land of vulture capitalism.

Such faith in the social superiority of family firms is the reason why Germany exempts most heirs of businesses from…

The Economist: Europe