“Did I request thee, Maker, from my clay

To mold me Man, did I solicit thee

From darkness to promote me?”

-John Milton, Paradise Lost

By Jonathan Morris, Antiscribe.com

This past Sunday I attended, for the second time, a high definition screening of the Royal National Theatre’s production of Frankenstein, directed by Danny Boyle, which gave me an excuse (not that I ever really need one) to revisit the cinematic legacy of two of my favorite figures of popular culture, the brilliant but misguided Dr. Frankenstein and his tragic and terrifying Creation (much as I did with Sherlock Holmes last year).

Since its first telling in Mary Shelley’s landmark novel in 1818, the story of the man and the monster he made from the pieces of dead bodies and brought to life through scientific means has never ceased to enthrall audiences the world over. Too often simplistically classified as a horror story, the novel of Frankenstein transcends genre, standing as a masterpiece of both gothic literature and the Romantic Movement, as well as being one of the first true science fiction novels. While the horrific aspects of the story and most of the film versions would barely register as scary by modern standards, the core themes of Frankenstein – our conflicted perspectives on God, our ever-growing ability to master science and develop new technology, the limits of our knowledge and ambitions, the debate between nature and nurture, the relationships between parents and children, the markers we impose on people’s self worth, and the evils of hatred and prejudice – remain ingrained parts of both our physical and metaphysical existence; for these reasons, among others, Frankenstein has been a fixture in popular culture since before doctor and monster first appeared onscreen over a century ago.

Much like any other figure of comparable standing in popular culture, there’s really no such thing as a “definitive” Frankenstein. Having been adapted and reimagined repeatedly so many times over the years, no one version of either Frankenstein and/or the Creature/Monster ever made or yet to be made will ever manage to be everything to everyone. And thank God for that, because a big part of the fun and fascination of Frankenstein for me since I first discovered the story at age 7 is the sheer variety of ways that the story can be told, again and again and again. Needless to say, though, some versions are certainly better than others, and some are more horrible that anything any mad scientist could ever slap together.

Some caveats: this is not meant to be an exhaustive oveview of all Frankenstein movies, but merely a selected survey of significant films, made for both film and television, that fall within the parameters of mainstream moviemaking. I also tried to keep it limited to films that were direct interpretations of the archetypal Frankenstein story, and not postmodern variations of it. Therefore, there’s no I Was a Teenage Frankenstein, Jesse James Meets Frankenstein’s Daughter, Frankenhooker, or that Japanese-made Battle of the Gargantuas prequel that saw a four-hundred foot Frankenstein monster defending the Earth from equally large alien menaces (that last one was, of course, a painful omission). Also, no Re-Animator (okay…that one actually was a painful omission – I <heart> Jeffrey Coombs).

And by the way, I’m not one of those people who get all hung up on how referring to the Monster as “Frankenstein” is incorrect; sons, after all, generally take their fathers’ names…

Now then, let’s all follow the call of nature and raise a toast to Gods and Monsters…and away we go…

Frankenstein (1910)

Charles Stanton Ogle was the first person to play the Frankenstein Monster on screen in a version produced by the Edison Company. Any similarities to a giant carrot are completely coincidental.

This Edison Film Company production, the first known screen version of Frankenstein, represents more of an interesting curio than a compelling work of cinema (at least by modern standards). Running approximately 10 minutes in length, the movie featured Charles Ogle as the Creature and Augustus Philips as Victor Frankenstein and, like most films of its time, was shot very much in static tableaux, without close-ups and with nearly every scene described beforehand by title cards (for example: “TWO YEARS LATER FRANKENSTEIN HAS DISCOVERED THE MYSTERY OF LIFE”). Still, it isn’t without its points of interest; Ogle cuts a particularly grotesque figure as the Creature and the creation sequence is an intriguing example of early cinema “trick film” special effects. Also, rather tellingly given the censorship issues that later versions would run into, there’s virtually no direct indication here that Frankenstein made his monster out of dead bodies; here the Creature is created through entirely chemical means.

Frankenstein Factoid: The Edison Frankenstein was, for many years, thought to be a lost film, meaning that there were no copies believed left in existence; a viable, viewable version wasn’t discovered until the 1970s, and it wasn’t until just a few years ago that the movie became widely available via online viewing (which can be done here). The only other two known silent film versions of the story, 1915’s Life Without Soul and 1922’s Italian produced Il Mostro di Frankenstein are, tragically, still classified as lost.

Frankenstein (1931)

It’s honestly hard to think of too much to say about James Whale’s iconic film version of Frankenstein, or the legendary performance by Boris Karloff that anchors it, that hasn’t already been said elsewhere and often. Needless to say, Karloff’s embodiment of the Frankenstein Monster, as well as Jack Pierce’s pioneering make-up design, has become the prevailing image of the Creature in the popular imagination, and the one by which all later versions are inevitably compared.

The film’s story only bears a passing resemblance to Shelley’s original novel, and actually owes far more to over a century’s worth of theatrical adaptations: Henry Frankenstein (Colin Clive), a brilliant young medical student, assembles a man from the bodies of the dead, but after accidentally implanting a criminal brain into his misshapen and deformed new creation, discovers that his best laid plans have yielded an inhuman monster. Instead of the eloquent, philosophical figure of the original novel, the film’s Monster is a mute creature with an undeveloped intellect, yet one no less tragic than his literary forbear. While Karloff was genuinely terrifying to audiences at the time, a large part of why his Monster still works so well today lies in the fact that he’s more pitiable and sympathetic than genuinely monstrous. Though Jack Pierce deserves worlds of credit for devising and executing the Monster’s unforgettable look, it was what Karloff did with movements, gestures, grunts, growls, wails, and whines that made his Monster the one for the ages.

In the role that made him both a star and a legend, Boris Karloff gave the world a Frankenstein Monster against which all Monsters would be compared.

Universal’s Frankenstein was defined by more than just Karloff’s monster, however; Colin Clive’s performance as the occasionally manic Dr. Frankenstein also set the gold standard for mad scientists, and his iconic “It’s alive! It’s alive!” may be some of the most famous lines in Hollywood history. In addition, James Whale, though only beginning his career as a film director, also displayed outstanding visual flair, expertly using close-ups and depth of staging as well as an aesthetic buoyed by a heavy influence of German expressionism. Overall, the film, like Tod Browning’s Dracula before it, not only helped establish the beginnings of the Universal Horror legacy but of horror movies in general.

“It’s alive! It’s alive!” Both manic and eloquent, Colin Clive set the standard for mad scientists in the movies.

While I love the movie, it certainly isn’t perfect. Its threadbare story doesn’t maintain over the course of the film and is fraught with contrivances; for some it’s also a little stilted by modern standards and many have criticized its lack of a musical score, though I personally think it uses ambient sound and minimalism brilliantly at times. In addition, the comic relief, especially from Dr. Frankenstein’s father – the curmudgeonly Baron – feels awkward, dated, and out-of-place. These are all negligible flaws, however, and one certainly can’t argue with either success or legacy. No Frankenstein film, and few films in general, has ever had the cultural footprint of this one, and more likely than not, no other one ever will.

A scene that from “Frankenstein” that was later edited for content; personally, I always felt that the edited version, which left more to the imagination, was significantly more effective.

Frankenstein Factoid: Though again, not terrifying or eyebrow-raising by today’s standards, Frankenstein ran into serious problems with censors all over the country, and in many areas its main release cut was significantly edited by local censorship groups. When it was rereleased in 1938, after the implementation of the Production Code and the Hayes office, Universal made some notable cuts to the film, including the famous sequence of the Monster throwing a little girl into a river and Frankenstein’s notoriously blasphemous line “In the name of God, now I know what it feels like to be God!” Most of the cuts were restored to the film in the 1980s, though the “God” line wasn’t actually restored until Frankenstein was first released on DVD in 1999.

The Bride of Frankenstein (1935)

The Monster and his Bride – Boris Karloff and Elsa Lancaster made for a brief but unforgettable couple.

Again, one of the most oft-analyzed films of Classical Hollywood – especially by queer theorists, due to it being openly gay director James Whale’s magnum opus – it’s hard to even find platitudes and insights for this movie that wouldn’t feel recycled. Simply put, The Bride of Frankenstein stands as one of the greatest sequels in Hollywood history and one of the greatest horror movies of all time; it’s undeniably the best Frankenstein movie. Again, despite a prologue featuring Mary Shelley (Elsa Lancaster, who also doubles as the Bride), the film has only a passing resemblance to the book: picking up on where the first film left off, Dr. Frankenstein (Clive), after barely surviving his showdown with the Monster, is lured back into the practice of playing God (“…if you prefer your Bible stories…”) by the nefarious Dr. Pretorius (an unforgettable Ernest Thesiger), this time with the idea of creating a woman. Unfortunately for Frankenstein (and well, pretty much everybody), his original creation, angrier and even more disfigured than before, also survives, and is now demanding a mate. Literally, in fact, for the Monster has learned to speak…

The Monster speaks! “The Bride of Frankenstein” gave Karloff greater leeway in developing the Monster’s character – in my opinion, it stands as his best individual performance.

The Bride of Frankenstein is everything that we’ve forgotten a sequel is actually supposed to be: an improvement over the original in every conceivable way. As a filmmaker Whale had grown leaps and bounds since the first film, and here was operating in the prime of his creative powers. The script, credited to William Hurlbut, was significantly more brilliant and layered, and the performances across the board were a class above just about anything in the original – even Karloff’s, as the Monster’s new verbal capabilities gave his performance as the Monster an extra dimension, as did Jack Pierce’s more refined and detailed make-up. As good as Karloff is, it’s Thesiger who steals the movie as the flamboyantly Mephistophelean Pretorius. The film also more expertly combined a dark, sardonic sense of black humor far more organically than the first film did, making Bride a sometimes hilarious parody of itself. Finally, filling a void that many felt hurt the first film is Franz Waxman’s musical store, an expert blend of harmonic character motifs – kind of like if Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf was reinterpreted by Wagner. All told, the film is so brilliantly done that you won’t even mind that when the actual Bride shows up – SPOILER WARNING – she really doesn’t do much of note.

Ernest Thesiger as the unforgettably evil – and hilarious – Dr. Septimus Pretorius, surrounded by a number of his own “creations.”

Queer theorists have gone back and forth about how much overtly gay subtext is actually apparent in the film, but there’s no doubt that The Bride of Frankenstein was an early example of camp humor in mainstream Hollywood film – mostly through Thesiger’s wonderfully outrageous performance and dialog. The movie is also amazingly rife with subversive imagery and dialogue, especially in regards to popular Christianity, and much like the first film, ran into major trouble with the censors because of it.

This scene, where the Monster is posed in similar fashion to Christ at the crucifixion, was one of the more subversive images that were snuck past the censors in “The Bride of Frankenstein.”

Frankenstein Factoid: Whale, though best known for the Frankenstein films, was also significant for being the first openly gay director in Hollywood history. Though his career was comparatively short, he was also responsible for the Invisible Man (1933) and what many consider the definitive film version of the musical Showboat (1936). Though popular legend states that his openness about his sexuality led to the end of his career, the truth is that he simply grew disillusioned with Hollywood after Universal significantly edited one of his films and had invested wisely enough by that point that he never needed to actually work again.

The Son of Frankenstein (1939)

Pictured left to right: Bela Lugosi as Ygor, Boris Karloff as the Monster, and Basil Rathbone as the Son of Frankenstein.

The third of Universal’s Frankenstein movies and the last to star Karloff as the Monster, this marked the beginning of a resurgence in the studio’s horror output after the company changed ownership in the late 1930s (and after a very successful re-release of both Dracula and Frankenstein). Unfortunately, The Son of Frankenstein had almost no continuity with the earlier films and the Monster regressed from a being a tragic, sympathetic creature into a hulking, homicidal brute (though he has a few nice human moments). After being raised abroad, the adult son of the original Dr. Frankenstein (Basil Rathbone) returns to his ancestral home with his wife and young son, only to receive a chilly reception from the locals, led by Krogh (Lionel Atwill), the local constable who lost his arm during one of the Monster’s original rampages. Despite this, it’s not long before Frankenstein Jr. is again bitten by the Monster bug and tries to bring his father’s creation back to full power. The Monster, though, will only do the bidding of the homicidal Ygor (Bela Lugosi), a convicted killer with a permanently broken neck looking for revenge on the villagers who tried to hang him…

The Son of Frankenstein is well liked by many, and was certainly the best of the Universal Frankenstein films that followed (which isn’t saying that much), but I’ve honestly never been a huge fan of it. Rathbone gives one of his most bland and forced performances as the eponymous lead, and the Monster playing second fiddle to Ygor (who, it should be noted, wasn’t the hunchbacked lab assistant commonly portrayed throughout pop culture) was just a little too steep a fall from The Bride of Frankenstein for my tastes. The film does have some nice, creepy, and even poignant moments, and features good performances from Karloff, Lugosi, and Atwill. Karloff left the series at this point of his own accord, feeling that the Monster he made famous had descended into caricature; Universal’s subsequent films would prove him to be correct.

Frankenstein Factoid: Though it’s hard to completely know where truth ends and apocrypha begins, it’s been well established by film historians and the Universal archives that the part of the Monster in the original Frankenstein was earmarked for Lugosi, under director Robert Florey. Supposedly, there was even a screen test done of Lugosi in some protean Monster make-up; though there have been reasons floated around over the years, mainly stating that Lugosi turned it down, the exact reason both he and Florey were removed from the project still remains a point of conjecture. Also, in contrast to popular belief, and perpetuated by Tim Burton’s heavily fictionalized Ed Wood, Karloff and Lugosi, while not close friends, weren’t staunch rivals and always got along professionally; including the Son of Frankenstein, the two starred in eight films together.

The Later Universal Films – The B Movies

From “The House of Frankenstein” – Glenn Strange as the Monster and Boris Karloff as the film’s mad scientist, Dr. Niemann.

Besides being Karloff’s farewell to the Monster, The Son of Frankenstein was also the last of the original Universal Frankenstein movies to be considered an “A” movie. All subsequent movies, with the exception of Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein were “B” movies with generally very little continuity, if any, from picture to picture. The first of the sequels was The Ghost of Frankenstein, which featured Ygor and the Monster (now played by Lon Chaney, Jr.) seeking out another of Frankenstein’s sons (Cedric Hardwicke) to restore the Monster to health. Spurred on by a visitation from his father’s ghost (also Hardwicke), the good Doctor decides to help the Monster through brain surgery, which goes pretty much as well as it did the first time around. It wasn’t a horrible movie, and indeed had some fun ideas, but Chaney never really worked as the Monster. This was followed by Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man, which featured Larry “The Wolf Man” Talbot (Chaney) inadvertently freeing the Monster (now played by Lugosi) while searching for a cure for his lycanthropy. The first part of the movie with the Wolf Man dealing with his resurrection from the dead is pretty good stuff, but the second half with Lugosi and the final clash between the two monsters is a major letdown. The last two of the proper Universal Monster movies, The House of Frankenstein and The House of Dracula, derisively referred to by Boris Karloff as “monster clambakes,” were pretty much badly written, uninspired, cobbled-together cash-ins by Universal with Dracula, the Wolf Man, and the Monster, now played by Western actor Glenn Strange; Karloff himself played the Mad Scientist, named Niemann, in The House of Frankenstein, but refused to come back for its follow-up. The original Universal Monster era wrapped up on something of a strong note with the Abbott and Costello movie, which again featured Dracula, the Wolf Man, and Strange again playing the Frankenstein Monster in comedic hijinx with the titular comedy duo. Though widely considered the best of the Abbott and Costello movies, it also perfectly symbolized how Frankenstein had descended so completely into being hackneyed, jokey cliché.

Lugosi in close-up during his only appearance as the Frankenstein Monster in “Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man.”

Frankenstein Factoid: SPOILER WARNING –In the original cut of Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man the Monster was originally supposed to be able to speak, carrying through on the fact that Ygor’s brain was transplanted into the Monster’s body at the end of The Ghost of Frankenstein; this led to the Monster speaking with Ygor’s voice, but being rendered blind in the process. This was the main reason why Lugosi, despite being 60 at the time of the film’s production, was cast as the Monster in Meets the Wolf Man. When the Lugosi-accented Monster provoked laughter from test audiences, the film was reedited to remove any references to the Monster’s blindness or speech. As a result, most of Lugosi’s performance was actually relegated to the cutting room floor and many of the Monster’s surviving scenes are represented by stand-ins since Lugosi, due to age, was unable to perform in many of the film’s more physically taxing scenes. Because of this, the cliché of the Monster being a clumsy brute that walks about with arms outstretched stems from the film’s surviving footage of Lugosi playing a blinded Monster.

The Hammer Frankenstein Series (1957-1974)

The Hammer “Frankenstein” films were focused on the mad experiments of Dr. Frankenstein instead of a reccuring Monster.

In the 1950s, horror movies took a marked turn away from the Gothic and supernatural towards hokey science fiction, most notably in the form of oversized monsters created predominantly by nuclear energy and directly fueled by popular paranoia over the emergence of atomic weaponry (and/or Communism). In the United States this came in the form of “giant bug” movies like Them! and nuclear accident films like The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms, and in Japan through the emergence of the kaiju genre (most notably Godzilla). Over in Europe, however, midlevel studio Hammer Film Productions, looking to fill a void in the marketplace conceived the idea of recreating Frankenstein for a new generation. As a way of separating their film from the earlier versions, and to avoid a lawsuit from Universal, Hammer presented a radically different take on the Frankenstein mythos. Instead of black and white movies dependent on the implication of horror and gore, the Hammer films were shot in vibrant color with depictions of violence, gore, and sexuality far more explicit than just about anything seen in movies before (though still tame by modern standards). The Hammer Frankensteins had an even more primary difference from Universal’s: while the latter told of the story of the man but focused on the Monster, in the Hammer films, the Man was the Monster.

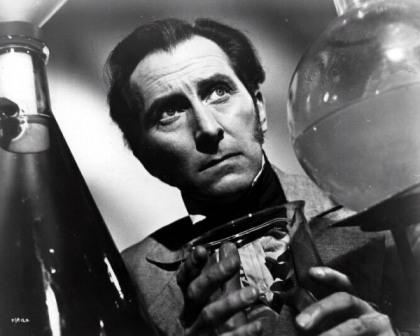

“The Man as the Monster.” Peter Cushing, who played Dr. Frankenstein in all but one of the Hammer series, played the mad scientist as ruthless sociopath with a severe God complex.

As played by the dynamic Hammer stalwart Peter Cushing, Baron Victor Frankenstein wasn’t the misguided but ultimately noble leading man that Colin Clive and Basil Rathbone played two decades earlier, but an often evil, ruthless, murderous, yet occasionally charming sociopath with a God complex who never let issues of ethics, morals, conscience, or the sanctity of human life get in the way of his scientific ambitions. Cushing played the scurrilous Baron in six out of the seven Hammer Frankenstein films, beginning with The Curse of Frankenstein (1957), Hammer’s extremely loose adaptation of Shelley’s novel. Curse pretty much was a basic retelling of the archetypal Frankenstein story and honestly wasn’t a terrific movie now or then, though it’s undeniably compelling with a level of craftsmanship that completely belied what was actually a very small budget. Christopher Lee played a creepy, albeit one-dimensional, Monster, the only time he did so, and the film packs a few nice jolts. Its importance to the history of horror film can’t be understated, however; under director Terrence Fisher and screenwriter Jimmy Sangster, the film defined what is, to this day, regarded as the “Hammer style,” and its tremendous success in both the U.S. and Europe led to a resurgence of the subgenre of Gothic horror, and a return to prominence of Frankenstein and other classically influenced movie monsters.

From “The Curse of Frankenstein,” Christopher Lee in his only appearance as the Creature; though Lee was a very solid and scary monster, he detested the make-up and found the scope of the performance to be too limiting for his tastes.

While I’m certainly someone who enjoys the films for what they are, it needs to be said that none of the Hammer Frankenstein films were especially great, or even very good. In all, the series was frustratingly defined by very intriguing ideas executed with often little ambition (and being fair, low budgets) and displaying very little continuity from film to film. Even the Baron, though more or less a consistently right bastard, could vary in the degrees of his evil, appearing as well-meaning but aloof in one film (Frankenstein Created Woman) and then being a blackmailing rapist and murderer in the next (Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed). To the series’ credit, though, not every film involved the mad scientist trying to create some kind of cadaverous ogre; very typically the films centered on Frankenstein involving normal, well-meaning people in his potentially ground breaking but morally dubious experiments, which could center on things like brain transplantation or capturing the human soul, only to have something horrible go wrong. In fact, the best films in the series, in my opinion, were the ones that didn’t involve a stereotypical monster.

In the Hammer films, Baron Frankenstein wasn’t always trying to create a cadaverous ogre, as this image from “Frankenstein Created Woman” clearly demonstrates.

It’s been a pretty general consensus that the best of the Hammer Frankensteins was the second film, The Revenge of Frankenstein (1958), which, par the course for the series, centered on a compelling and thought-provoking science fiction concept: the Baron transferring the brain of his deformed lab assistant, willingly, into a newly created “perfect” body. What set it above the others was that it carried through on the idea rather effectively, and without blissfully ignoring the philosophical implications of its story. My choice for worst of the series would be The Horror of Frankenstein (1970), the only film to not star Cushing, which was a lousy parody-remake of Curse. The series also featured The Evil of Frankenstein, and the final film in the series, 1974’s Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell, essentially helped marked the end of the Hammer Horror cycle.

Though Hammer’s Frankenstein films are notable for reigniting interest in Gothic horror after years of atomic-fueled ants, lizards, spiders, and the like, Baron Frankenstein, a brilliant scientist willing to push the boundaries of scientific discovery no matter how devastating the cost, may very well have been as potent an allegory for nuclear terror as any atomic monster…

Hammer’s Baron Frankenstein may not have been fifty feet tall or radioactive, but his personficiation of unchecked scientific ambition reflected the nuclear paranoia of the time.

Frankenstein Factoid: The Monsters in the final two series entries, Horror and Monster from Hell, were both played by the then six-and-a-half foot tall David Prowse, who would later go on to play the physical role of Darth Vader in the original Star Wars trilogy (opposite Cushing’s Grand Moff Tarkin).

Frankenstein 1970 (1958)

Directed by independent producer Howard Koch, this attempt at a futuristic Frankenstein movie represented Boris Karloff’s return to the subject after almost fifteen years; this time, though, it was as the original Dr. Frankenstein’s grandson now trying to use atomic energy to create his own Monster. To finance this, he rents out his ancestral castle to a visiting film production, which only leads me to rationalize that someone somewhere thought fissionable material would have been shockingly cheap by the time 1970 came around. A spectacularly bad movie, and enjoyed by some for that very reason, this was one of the worst films of Karloff’s career; there is an intriguing idea mixed in here and there, and one of them – Dr. Frankenstein being tortured by the Nazis for refusing to help them – actually informed one of my own unsold movie pitches many years ago.

Frankenstein Factoid: The real man behind the cinema legend of Boris Karloff, or Karloff the Uncanny as he was known during the heights of his popularity, wasn’t actually named “Boris Karloff.” Karloff’s real name was William Henry Pratt, and he was, from all accounts, a very proper Englishman who would sometimes hold up filming so he could enjoy his afternoon tea. Though there have been numerous theories posited over the years, some by Karloff himself, there has never been a definite account of the origin of the distinctive stage name; Karloff himself had neither Russian nor other Slavic ancestry, being of Anglo-Indian heritage.

Frankenstein (1973)

This was a made-for-television adaptation of the Frankenstein story that was produced and co-written by Dan Curtis, creator of the Dark Shadows TV series and the original Night Stalker films, that first aired in two parts on ABC television back in January 1973. Though produced on video instead of film, thus making it look very inauthentic, unrealistic, and dated, this is actually a pretty good adaptation, with the meat of the story dynamics derived faithfully from Shelley’s novel. Robert Farnsworth played Victor Frankenstein as a very conflicted soul, with Swedish-American actor Bo Svenson giving a sensitive performance as the Creature. This was actually one of the first Frankenstein adaptations in the United States to hew closely to the original source material, presenting the Creature as an entirely sympathetic figure and the Doctor as the one who, despite his best intentions, was largely in the wrong.

Frankenstein Factoid: While the common image, informed heavily by Karloff, is that Frankenstein’s creation was a lumbering patchwork ogre of limited intelligence and, at best, childlike speech patterns, Shelley’s original conception was of an unnaturally athletic giant with a brilliant, philosophical mind who could and would quote from the Bible, Shakespeare, and Milton. In some respects, Svenson was a strong choice to play the part; according to his IMDB bio, during the early 1970s he was a PhD. candidate in Metaphysics at UCLA after spending six years serving in the United States Marine Corps.

Andy Warhol’s (Flesh for) Frankenstein (1973)

Pictured: Serbians.

In some respects the culmination of years of Z-grade, low budget, sleazy Frankenstein films made both in the United States and Europe, this gory, oversexed, and terminallly weird version of the story centers on the mad scientist (Udo Kier) trying to propagate a Serbian master race (Serbian?) by creating the perfect Serbian male and female from a plethora of body parts (assumedly Serbian body parts). Irritated that his male isn’t interested in getting his freak on, Frankenstein murders a local man for his brain, mistaking him for the local stud (Joe Dallesandro), who then comes looking for payback. Plotted almost entirely like a bad, bad porno (and that’s by pornography’s standards), this film understandably received an X rating when it was first released back in the 1970s; many shorter, edited versions also exist, hence the movie’s imprecise name. Even by today’s standards, this remains a colossally disgusting waste of time; case in point, there’s a scene where Dr. Frankenstein has sexual intercourse with his female creature’s open wounds (I don’t think Serbians do that). The movie does have a cult following, but trust me…that’s not a cult you want to join. Andy Warhol, by the way, was one of the film’s producers; it was actually directed by associate Paul Morrissey. It was also originally shown in 3D, demonstrating that gross misuse of the format is hardly a new phenomenon.

Dr. Frankenstein really, really likes his Serbians.

Frankenstein Factoid: Andy Warhol, besides having been the iconic head of the Pop Art Movement, was also known for his role in how we define modern celebrity, running in circles with many actual and aspiring celebrities between the 1960s and the 1980s. Mary Shelley herself ran in similar circles in her day, associating briefly with the notorious George Gordon Byron, known better as Lord Byron, who many regard as history’s first international celebrity.

Frankenstein: The True Story (1973)

Capping off a busy year for Frankenstein adaptations was this prestige-style British-made version that aired on NBC in the fall of 1973. Title notwithstanding, and in contrast to a prologue by star James Mason, this was not a faithful adaptation of the novel but more an extremely revisionist variation on its core ideas and its set pieces, as well as the Hammer films. In this version, the young Dr. Victor Frankenstein (Leonard Whiting), traumatized from his brother’s drowning and seeking to discover the mysteries of life and death, falls under the spell of two scientists, the iconoclastic Dr. Clerval (David McCallum) and the villainous Dr. Polidori (Mason). With Clerval’s help and, after his sudden death, his brain, Frankenstein brings his creation to life; in this version, though, Frankenstein actually does create the perfect man, played by the “beautiful” Michael Sarrazin, and tries to help him adjust to civilian life. Of course, their “happy home” doesn’t last once the process begins reversing itself, gradually turning Frankenstein’s living Adonis into a deformed, walking corpse…

“Beautiful.” Michael Sarrazin during his first appearance as Dr. Frankenstein’s Creature in “Frankenstein: The True Story,” which presented an entirely different take on the Creator-Creature dynamic.

Though due in no small part to its unique creator-creation dynamics, this ranks as one of the most fascinating Frankenstein films yet made, incorporating many of the ideas that were explicitly introduced in the Hammer films but carrying them through into a compelling narrative that explores their implications. It’s also features a very pronounced queer subtext – not surprising as it was co-written by Christopher Isherwood. In this case, the relationship between Frankenstein and his creation isn’t one of parent-and-child but a domestic partnership; Frankenstein is also turned away from the heteronormativity of his fiancé and family life at the behest of Clerval and then Polidori, and after initially embracing his Creature he ultimately rejects it after its looks begin to rapidly fade. Indeed, one of the unintentionally eerier elements of the film comes in the fact that the Creature’s early disintegration very closely resembles that of the late stage AIDS victims who began emerging in the gay community about ten years later.

Beauty fades, as Sarrazin’s Creature steadily decomposes over the course of the film.

Frankenstein: The True Story does have some marked flaws: at nearly three hours in length, it’s very overlong and the actual character of Frankenstein is far, far too passive in the overall story. It also runs far afield from what many would expect from a Frankenstein movie, and at times seems much more like a costumed melodrama than horror movie. Still, besides its intriguing take on the tale, it boasts a fantastic cast, supported by John Gielgud, Ralph Richardson, Agnes Moorehead, and Tom Baker in minor roles, and Jane Seymour as a very evil incarnation of the Bride. Somewhat forgotten and overlooked by many Frankenstein and horror aficionados, this version represented an important step in the popular perception of Frankenstein as something more high brow than the B-movie clichés that had been perpetrated in the previous decades.

Frankenstein Factoid: The character played by James Mason, Dr. Polidori, was not in Shelley’s novel, but his name was taken from one of her known associates, Dr. John Polidori. Polidori was the friend and personal physician of Lord Byron, but is better known today as the writer of The Vampyre, a short story widely regarded as the progenitor of all vampire fiction.

Young Frankenstein (1975)

Frankenstein and his Monster (Gene Wilder and Peter Boyle), performing “Puttin’ on the Ritz” in “Young Frankenstein.”

For me, Young Frankenstein was the film that actually spawned my love of Frankenstein movies; it was the first one I ever saw, and my enjoyment of it prompted my father to rent Frankenstein for me, which itself was the first “classic” movie I ever saw. In the broader scheme of things, however, Young Frankenstein represents one of the best spoofs ever made and director and comedy legend Mel Brooks’s best film. Heavily inspired by the plot and iconography of The Son of Frankenstein, right down to being shot in black and white, it tells of Friedrich Frankenstein (pronounced Frahnc-en-steen), played by Gene Wilder (who co-wrote the script with Brooks), who returns home after spending his professional career running from his family’s infamy. It’s not long, of course, before young Frankenstein, along with his curvaceous lab assistant Inga (Teri Garr) and (supposedly) hunchbacked henchman Igor (Marty Feldman), gets around to making a monster of his own (Peter Boyle), though with results more hilarious than horrific.

A big reason why Young Frankenstein works so well and is so well regarded is because it’s obviously made with great love and admiration for its source material, with its humor drawn much more from its story, characters, and dialog than out of any misplaced animosity towards old Frankenstein movies. In fact, take out its gags and humor and this could have very well been a classic straight Frankenstein movie, making it not only one of the best comedies of all time, but one of the best versions of Frankenstein ever made.

One of the reasons “Young Frankenstein” works so well is that it is, first and foremost, a “Frankenstein” movie.

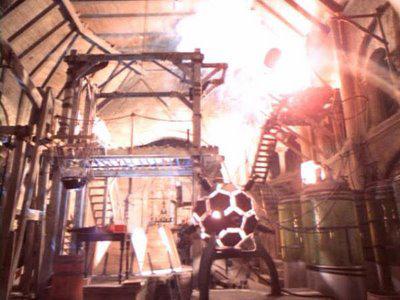

Frankenstein Factoid: While looking to replicate the electrical equipment used in the laboratory in the original Universal Frankenstein, the producers got in touch with Kenneth Strickfaden, the electrical engineer and set designer who crafted the various devices in the original film. By an amazing stroke of luck, Strickfaden still owned many of the quirky devices used for the original film, and they thus were used again in the laboratory in Young Frankenstein.

The Terror of Frankenstein (AKA Victor Frankenstein) (1976)

Because nothing truly puts terror in one’s heart like BLACK LIPSTICK…Per Oscarsson’s forgettable take on the Creature.

An Irish-Swedish co-production, this obscure film is an extremely faithful interpretation of the original novel (even though they misspell Mary Shelley’s name in the credits), but suffers from very low production values, a bland visual style, and some brutally insipid performances. This version of the Creature (played by Per Oscarsson) is also particularly lame, being neither terrifying nor even remotely convincing; he isn’t even ugly enough to be believably scary. Nothing really to see here, but it might be interesting for die-hard fans or admirers of the novel, and it’s readily available on both Youtube and Hulu.

Frankenstein Factoid: There’s a very good reason why many Frankenstein features, despite being adaptations of the original novel, have to be titled something other than simply Frankenstein: while the novel is in the public domain, Universal owns the rights to Frankenstein as a feature film title. Ergo, Hammer, for instance, had to title its version The Curse of Frankenstein and this version was entitled The Terror of Frankenstein.

The Bride (1985)

“The Bride” was a failed attempt to do a revisionist remake of ”The Bride of Frankenstein” for the post-feminist era.

This unofficial remake/sequel to The Bride of Frankenstein isn’t as bad a film as its reputation would suggest, but what’s bad about it…is still plenty bad. Essentially beginning where the earlier film ended, Baron Frankenstein (Sting) brings his latest creation, a female companion (Jennifer Beals) for his Creature (Clancy Brown) to life. Struck by the Bride’s beauty, the Baron reneges on his deal, leaving the heartbroken Creature for dead in the ruins of his laboratory. He then takes the Bride under his wing, intending to make her the epitome of a new, liberated woman, only to eventually try to possess her as his own. Meanwhile, the Creature, surviving his ordeal, meets a precocious circus dwarf (David Rappaport), who befriends the lost soul and teaches him self-respect. In the end, The Bride proves to be a shining example of a great idea, badly botched. The main concept behind the Bride’s part of the story, where a man’s desire for a free-thinking woman gets ultimately undone by his own hypocrisy, is a very compelling dynamic, but it’s ultimately ruined by portraying the Bride as a sniveling damsel whose idea of liberation involves little more than wanting to have sex with other chauvinist pigs. It doesn’t help any that both Sting and Beals are pretty lousy in their roles. The portion of the film with Brown and Rappaport, on the other hand, is terrific, and deserved to be part of a better film. The movie also pretty much killed Sting’s acting career, so it does have that going for it, too. In addition, the supporting cast featured a young Timothy Spall as the Baron’s hunchback assistant and, in a cute touch, gay icon Quentin Crisp briefly paying homage to earlier gay icon Ernest Thesiger’s role from the original Bride.

The main subplot of “The Bride,” centered on the Creature (Clancy Brown) befriending a precocious circus dwarf (David Rappaport), gives an otherwise lousy movie real heart.

Frankenstein Factoid: In another very nice tribute, the name of Rappaport’s dwarf character was named “Rinaldo” after Frederic I. Rinaldo, the screenwriter of Abbott & Costello Meet Frankenstein, who was retired in the early 1950s as a result of the Hollywood Blacklist.

Frankenstein Unbound (1990)

From “Frankenstein Unbound,” Raul Julia as Victor Frankenstein and Nick Brimble as a particularly deformed Monster.

This bizarre but very watchable mash up of science fiction, horror, and art film represented legendary director/producer Roger Corman’s return to the director’s chair after almost twenty years, and has, to date, been his final feature film. The movie stars John Hurt as a scientist from the future who finds his attempt to cause world peace by creating the ultimate weapon undermined when it causes strange “time slips” across the globe. After being sucked into one of these time slips, the scientist finds himself taken back to 1817 Switzerland, where he runs into a coldblooded scientist named Victor Frankenstein (Raul Julia), a young, aspiring author soon to be known as Mary Shelley (Bridget Fonda), and a very dangerous Monster (Nick Brimble). Neat concept, but the movie is pretty much a shaggy dog story, with a lot of interesting elements that fail to lead to anything especially coherent. Still, there are some very strong performances and its core theme, that we’ve become so irresponsible in regards to our own scientific progress that our own creations threaten to destroy our very world, ultimately carries it through.

Frankenstein Factoid: The title of Frankenstein Unbound is taken from the famous closet play Prometheus Unbound by the poet Percy Shelley (husband of Mary), and incorporated a similar theme of mankind, for better or worse, overthrowing its creator.

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1994)

If you head into seeing “Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein” with high expectations, then as the tagline states: Be Warned.

I remember vividly when, back in 1994, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein arrived in theaters buoyed by a great deal of advanced hype from Frankenstein fans. There had never been a faithful, big budget theatrical version of the Shelley novel up to that point, and this was coming off the heels of the very successful and admired Bram Stoker’s Dracula, which provided a very invigorated and fresh adaptation of a stale character. Adding to the hype was that the legendary Robert De Niro was going to be playing the Creature and Kenneth Branagh, who as an actor/director was hyped at the time as being either the next Laurence Olivier or Orson Welles, would be serving as both the film’s director as well as its Victor Frankenstein. Unfortunately, the end result was a massive letdown both critically and commercially, and one that pretty much derailed Branagh’s career.

Robert De Niro’s Creature gets an “A” for effort, but he just wasn’t suited to the character; the fact that he’s not especially large or terrifying didn’t help matters.

I’ve always been of mixed feelings on the movie itself. I still do enjoy it and find it to be a compelling telling of the story, but there can be no doubt that as a film it absolutely collapses under its numerous flaws. While Branagh was, at the time, highly regarded for bringing vibrancy to his Shakespeare adaptations, he was also highly superficial in his treatment of their core themes. In Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein he took largely the same approach, but this time overcompensated ridiculously for what he clearly didn’t think was a dynamic enough story on its own. The film’s constantly moving camera is thoroughly obnoxious, and its breakneck pacing pretty much has the opposite effect of what was intended, causing everything in the film to lack urgency or otherwise stand out.

Kenneth Branagh “played God” as both Frankenstein in front of the camera and the director behind it; the failure of the film was a major setback to what was, at the time, a very promising career.

From an acting perspective, Branagh was quite good as Frankenstein, and some of the supporting performances were solid (even if the casting, such as John Cleese as Frankenstein’s troubled mentor, was occasionally bizarre). Unfortunately, as the Creature, De Niro was completely out of his comfort zone as a performer, as his realistic Method style was ill-suited to such a fantastical character; the fact that the rest of the cast, including Branagh, came from a Classical background only caused his work to feel all the more disjointed. The script, co-written by Frank Darabont, is mostly solid, but ends up going very, very wrong at the climax, and makes the cardinal mistake of tragedy by having the tragic figure realize the error of his ways much too early in the story, thus pretty much killing all of its subsequent narrative momentum.

Frankenstein Factoid: Though she’s best known for Frankenstein, published when she was only 20 years old, in her lifetime Mary Shelley was a very well known, popular, and prolific author of several novels, short stories, and autobiographical pieces and articles, as well as editor of the works of her husband Percy Bysshe Shelley. Nevertheless, even up to a few years ago, many critics and theorists often portrayed Mary Shelley as secondary in stature to both her husband Shelley and her father, the novelist and philosopher William Godwin. Thankfully, with the rise of feminist criticism, the chauvinistic treatment of her legacy and her talent has given way to greater recognition of her abilities as a writer and greater analysis of her overall body of work.

Frankenstein (2004)

From the Hallmark Channel’s version of “Frankenstein,” Alec Newman played Victor Frankenstein, and Luke Goss played a very Goth-inspired Creature.

This version, made as a two-part miniseries for the consistently unprofitable Hallmark Channel, represents a meticulous-to-a-fault adaptation of the novel. Ex-rocker Luke Goss plays a very emo-inspired version of the Creature and Alec Freeman a youthful Victor Frankenstein; they’re both okay, which is probably the best summation I can think of for this version of the story. While it has some nice, literate touches in its script, and a strong supporting cast featuring Donald Sutherland and William Hurt (who steals the movie as Frankenstein’s guilt-stricken mentor), at almost three and a half hours in length it’s oppressively long; also, while shot on beautiful locations in Slovakia and Norway, it has almost no atmosphere or compelling visuals to speak of, and never manages to be especially scary nor intellectually invigorating enough to justify the time watching it.

Frankenstein Factoid: Though certainly open to interpretation, many Frankenstein scholars have speculated that the flawed character of Victor Frankenstein was heavily influenced by none other than Mary Shelley’s own husband, Percy Bysshe Shelley. Besides the fact that they had a tempestuous marriage, Percy Shelley, like Victor, had abandoned his child, as well as his first wife, to take up with the then Mary Godwin – his wife Harriet eventually committed suicide while pregnant with child. Shelley would also abandon Mary many times to take up with her stepsister, even while she was pregnant with their child, and also as a student had a noted interest in electricity. As for the inspiration for the orphaned Creature, Mary may well have looked to herself: her first child with Shelley died after being born two months premature, and her own mother, the feminist Mary Wollstonecraft, died giving her life in 1797.

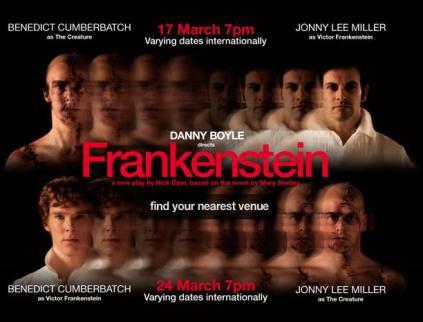

Frankenstein (2011)

As this overview has probably well-demonstrated, the best Frankenstein films have not been incredibly faithful to Shelley’s original work; while the novel is a masterpiece of subtext and symbolism, its story is highly internalized and not inherently very dramatic. This stage version, adapted by Nick Dear and directed by Academy Award-winner Danny Boyle, which was filmed for high definition screenings in the United States, is the best actual adaptation of the novel I’ve ever seen, largely because it directly addresses those problems. Instead of telling the entire story from the perspective of the morally ambiguous and often unsympathetic Victor Frankenstein, the first half of the play is told almost entirely from the perspective of the Creature, while the second half is then given over to Frankenstein himself.

The presentation of the Creature in this version is among the most dynamic ever, and perhaps the most three-dimensional. Following him from “birth,” the play depicts the Creature’s development from being an overgrown infant to something akin to a recovering stroke victim; in essence, he has to teach himself everything, regarding speech, motor coordination, and human interaction; in the process, he learns, painfully, about the cruelty of the world, and replies almost equally in kind. The Doctor, in contrast, is a self-centered misanthrope incapable of caring for another human being, let alone the Creature he left abandoned. While the play mostly follows the events of the novel, it embellishes and fleshes out many of the original novel’s subtexts and, like The Bride of Frankenstein did in 1935, infuses it with a fine vein of black humor.

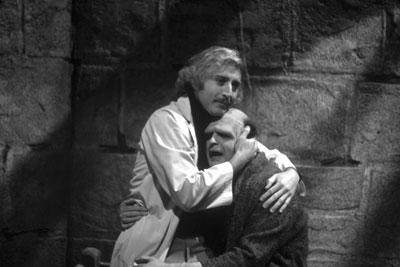

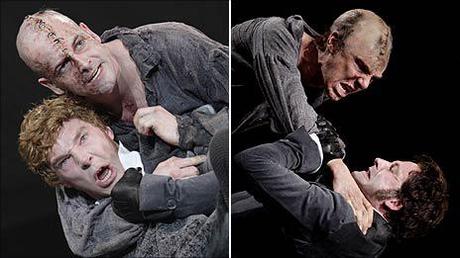

In the Danny Boyle/Nick Dear adaptation of “Frankenstein,” Benedict Cumberbatch and Jonny Lee Miller would alternate in performing Frankenstein and the Creature each night, emphasizing the inherent similarities between the two characters.

The central gimmick of the theatrical presentation was that the parts of the Creature and Creator were played by Jonny Lee Miller and Benedict Cumberbatch, who would alternate between characters with each performance; the idea, being more than just a gimmick, has the effect of demonstrating the thin line between both damaged souls. Having now seen both versions, I personally liked Cumberbatch as the Creature and Miller as the Doctor, but it was really just as compelling the other way around. At present time, there are no plans to release it to DVD, though it is being shown in encore screenings in theaters across the United States until August of this year, and given Boyle’s involvement, a proper film version seems inevitable.

Frankenstein Factoid: The dynamic of Frankenstein and his creation being mirror opposites of each other is hardly a new idea, as many theatrical versions into the early 20th century had both Doctor and Creature dressing and even acting alike. Also, a BBC adaptation for the series Mystery and Imagination in the late 1960s featured saw Ian Holm play dual roles as both Frankenstein and the Creature (in homage to the episode, Holm played Frankenstein’s father in Branagh’s 1994 version).

Afterword

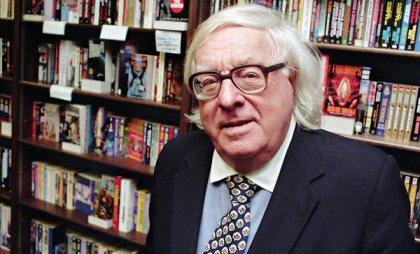

About ten years ago, while as an undergraduate at the University of Southern California, an elderly gentlemen in horned rim glasses stopped me to ask me direction to one of the buildings on campus. As irony would have it, I had just seen the man less than 24 hours earlier, in Kevin Brownlow’s documentary Universal Horror commenting on how the original Frankenstein movie scared him to death as a kid. That man was the great Ray Bradbury; fortunately, instead of just giving him directions, I offered to walk him to his destination. In the process I mentioned seeing him in the documentary, which he himself hadn’t seen yet, and he seemed to light up in talking about Frankenstein, and how angry his mother got as his brother for taking him to see it. As bad luck would have it, as I was writing this piece this week, the news came out that Ray Bradbury, bar none one of the greatest, most important, and most influential science-fiction writers of all time, passed away at age 91. I only spent five minutes with Mr. Bradbury, but I still find it an amazing and humbling notion that I once actually got to speak with him, not about his classic novels or stories, but about something that he and I had almost equal appreciation for: Frankenstein.

In the grander scheme of things, the influence that Mary Shelley’s creation undeniably had on Mr. Bradbury, is emblematic of the effect its had on our entire popular culture. Any story, in any medium, that tells of some scientific experiment or piece of technology gone wrong owes its debt to Frankenstein, and though here I’ve examined some of the most explicit examples of movies that sought to retell the actual story, time and again, the fact is that the piece of Frankenstein is in almost everything we watch, read, and play, and, more likely than not, probably always will be.

Ray Bradbury, 1920-2012.