At Talk to Action, Frank Cocozzelli discusses the mudsill theory of economics that originates with an 1858 defense of slavery by South Carolina Senator James Henry Hammond. As Frank notes, the Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines "mudsill" as

1. a supporting sill (as of a building or bridge) resting directly on a base and especially the earth; 2. a person of the lowest social level.

Hammond applied the analogy to the socioeconomic construction of society, arguing that every society needs "a class to do the menial duties, to perform the drudgery of life." Unlike the "class which leads progress, civilization, and refinement," members of the mudsill class are (in the view of their "betters") characterized by "a low order of intellect and but little skill." In Hammond's theory, everything wonderful, good, and noble that any society constructs is built on the backs of a mudsill underclass who work at the good pleasure and direction of the wonderful, good, and noble folks at the top of society--its meritocratic elite.

And so why turn attention to an antiquated defense of an outmoded system of arranging people into upper and lower classes, into masters and slaves? Frank argues--very persuasively--that the mudsill theory is hardly a thing of the past. It's still with us. It dominates the thinking of contemporary libertarians who celebrate the theory of the Austrian School of Economics--which is, as Frank notes, eerily akin to the mudsill theory promoted by Hammond and other defenders of slavery in the antebellum South.

Frank writes,

"Mudsillism" allows for the select few to use other human beings to generate wealth without providing just compensation. And although we don't call it that, Mudsillsm is resurgent in America as wages are stagnant or in decline despite the increases in worker productivity. Increasingly, average Americans work longer and harder while shareholders and executives are rewarded far beyond their contributions. And personal indebtedness to financial institutions replaces wages that, in turn, replaces liberty with dependence. Indeed, if libertarian economics were to prevail, the result would be local theocracies, restricted education, and the hierarchical economic castes.

I think Frank Cocozzelli is absolutely correct with this analysis. And as I read it in light of the hot defenses of "religious liberty" as a right to discriminate that we've been seeing in recent days as gay-discrimination bills are discussed in the U.S., I see a very strong link between those hot defenses of "religious liberty" as freedom for me but not for thee, and the mudsill socioeconomic analysis of American slaveholders.

As Ian Milhiser and Harold Meyerson point out in articles I've cited in previous postings today, the argument that God has given me a divine right to discriminate against you and to use you as an object in my socioeconomic games hardly originates with the contemporary religious-freedom-for-me-but-not-thee crowd. It was part and parcel of the rhetoric of those--including many white church leaders--who resolutely opposed the ending of legal segregation in the American South in the 20th century.

And in our opposition to the extension of human rights to people of color in the mid-20th century, we white Southerners were self-consciously echoing the arguments that our slaveholding ancestors had applied a century earlier as they opposed the abolition of slavery. Arguments that had a very strong religious basis and biblical resonance to them, and which defended as the divine intention the arrangement of society into upper and lower, better and inferior, planner and doer, director and mudsill base, and exploiter and exploited . . . .

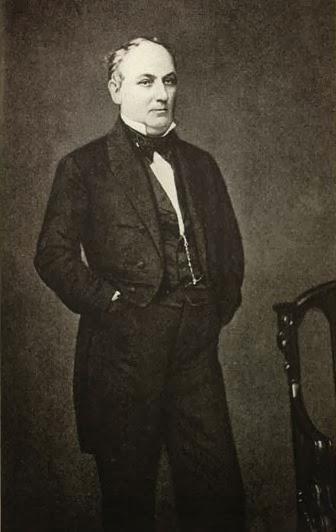

The photograph of James Henry Hammond is from a Wikipedia article about mudsill theory.