The Soul Cages (blogspot.com)

Songs about death and dying aren’t exactly the norm where pop music is concerned. Nor are they the kinds of uplifting subjects that win the hearts and minds of music fans, either.

Now I know that Austrian composer Gustav Mahler’s moving voice and orchestra cycle, Kindertotenlieder (“Songs on the Death of Children”), is a classic example of the genre in the post-romantic realm. It’s also true the activities of folk-rock legends Neil Young (“The Needle and the Damage Done”) and James Taylor (“Fire and Rain”) resulted in two such numbers about self-inflicted death from drugs and suicide, respectively. Still, an entire album devoted to these concepts is a rare product indeed. Why, just the thought alone would be mind-blowing to record producers.

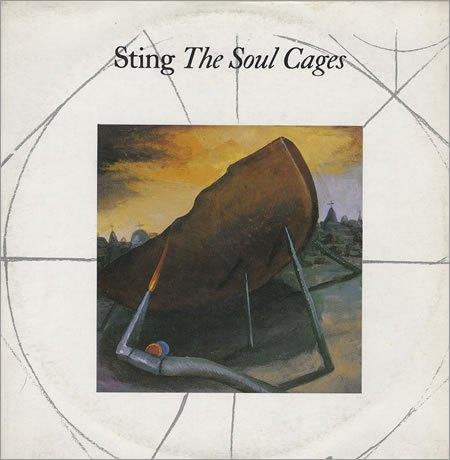

In English singer-songwriter Sting’s 1991 album The Soul Cages (A&M Records), however, for which he won a Grammy Award in 1992 for Best Rock Song, the tracks are fueled not by a violent end to life but by terminal illness – in this instance, his father’s sad demise from cancer (and, by inference, his mother’s earlier passing from the same disease). Critics have described this work as “gloomy,” “moody,” “highly serious,” “pretentious,” “dense,” “overtly literate,” “darkly lit,” and “almost Gothic.” And these were the favorable ones! If it’s happy-hour time you’re after, then you’ve come to the wrong place.

Nevertheless, The Soul Cages is an album I often turn to, whenever I have a moment alone with my thoughts or give in to private reflections about my own parents’ passing. There are nine numbers in toto, including an instrumental passage, “Saint Agnes and the Burning Train,” which comes at the midway point, a lovely lyrical respite from the prevailingly bleak atmosphere.

But hey, it’s not all gloom and doom, I’m here to tell you. This is a concept album that beats most such high-minded efforts by a sea-mile, a soul-searching voyage of discovery into Sting’s “personal heart of darkness” – and a pop-culture classic to set beside his other standards – that merits repeat hearings.

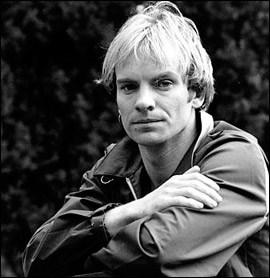

“This latest album has got the best reviews I’ve ever had – and the worst,” he was quoted as stating, back in 1991. “There’s a polarity about them which is quite extraordinary and, I suppose, in a way, confirming.” Yes, indeed. Confirming of life’s own polarities, such as they are, of the irreconcilable differences between what we perceive life to be and the ultimate reality of what our lives – and especially the end of our lives – can promise.

Writer’s Block

After …Nothing Like the Sun, his second solo outing, Sting experienced a severe case of writer’s block, a fallow three-year period wherein he “felt emotionally and creatively paralyzed,” as noted in his 2007 book Lyrics, “isolated, and unable to mourn. I just felt numb and empty, as if the joy had been leached out of my life. Eventually I talked myself into going back to work, and this somber collection of songs was the result. I became obsessed with my hometown [of Newcastle] and its history, images of boats and the sea, and my childhood in the shadow of the shipyards.”

Sting (cbsnews.com)

These images and more are there, in all their heavy profusion and portent, in The Soul Cages. “The theme of the album is essentially about dealing with death,” he went on. “For me, at my age, it’s an important subject,” as I’m sure it is for most of us mortals. “As soon as I remembered the first memory of my life, everything started to flow. The first memory was of a ship… it was a very powerful image of this huge [vessel] towering above the house. Tapping into that was a godsend. I began with that, and the album just flowed,” as did the second cut, “All This Time,” one of the rocker’s all-time bounciest strains:

And all this time, the river flowed

Endlessly to the sea

If I had my way I’d take a boat from the river

And I’d bury the old man

I’d bury him at sea

It’s a clue as to what Sting would have done to comply with his dad’s dying wish (“And I’d bury the old man, I’d bury him at sea”) – if he had had his way, of course. Now for the album’s abstruse title: “The title song,” Sting told Billboard Magazine, “is based on a fable about souls trapped under the sea in Davy Jones’ locker and how a sailor wagers the king of the sea to free them…”

Talk about a deal with the devil! That’s a whole lot of heavy lifting for an ace rock-n-roller to commit to, and a whole lot of philosophy for non-sophisticates to absorb and condense in one sitting. The effort will pay huge dividends, however, if one is patient and shrewd enough to listen to what the singer is trying to say. “When you lose both your parents,” he insisted, “you realize you’re an orphan. Sadness is a good thing, too, to feel a loss so deeply. You mustn’t let people insist on cheering you up.”

Far be it for me to step on anyone’s sullen thoughts. But the album is more than that: it’s a way of purging one’s being of the melancholy that persists after a loved one has departed this earth and is no longer around to offer guidance and hope.

“I think a lot of ghosts were exorcised with ‘The Soul Cages’,” he continued. “That album was very personal, confessional, and therapeutic in terms of facing death and loss. But I guess you could say the therapy worked, because now [back in 1993] I have a new sense of freedom, a desire to move on and make songs solely intended as entertainments, designed to amuse.”

Not to contradict a master songsmith, but there’s relatively little of what I would call “entertainment” in The Soul Cages, yet quite a lot that’s amusing – a welcome diversion from the “sting” of death, to put it plainly. For example, Sting pokes fun at the church and organized religion, a subject not so lightly lampooned, especially nowadays. With respect to the ecclesiastical, there are lyrics in “All This Time” that perfectly capture the sentiments of our era.

The song takes place in Sting’s fictional boyhood home, on the day his father breathed his last. He and dad are about to receive some visitors from the local parish, two well-meaning heralds of their faith:

Two priests came round our house tonight

One young, one old, to offer prayers for the dying

To serve the final rite,

One to learn, one to teach,

Which way the cold wind blows

Fussing and flapping in priestly black

Like a murder of crows

Such poetic imagery, such verbal dexterity! The lines about “fussing and flapping in priestly black like a murder of crows” are barely disguised barbs at authority figures and how they get away with “murder” by dint of their office, even when they’re about to administer the so-called “final rite,” with the color “black” referring to the Grim Reaper’s guise (albeit in clerical garb). There’s also a brilliant illustration of Sting’s use of the collective, i.e., “a murder of crows,” the kind of mastery of language that today is nowhere in evidence among our major songwriters.

Oh, but there’s more. Sting takes a quotation from the Sermon on the Mount – the Beatitudes, to be precise – and twists it around in the form of a challenge to the two priests, whereby he questions their (and our) belief in suffering as the ultimate validation for our existence:

Blessed be the poor, for they shall inherit the earth

Better to be poor than be a fat man in the eye of a needle

And as these words were spoken I swear I hear

The old man laughing,

‘What good is a used up world, and how could it be

Worth having?’

Dad gets his chance to voice the last word on the subject, and in a most upbraiding fashion. Sting repeats the main chorus, but concludes it by posing another question to his guests:

Father, if Jesus exists,

Then how come he never lived here?

Religion was never part of this Newcastle household, he’s saying. What makes these clerics think their coming will change the status quo to any degree? What follows is Sting’s childish taunt at the priests, in essence a musical thumbing of his nose, amid the lead guitarist’s strumming and the doubling of Sting’s voice:

Hiyeah, hiyeah, yeah

Hiyeah, hiyeah, yeah

The final stanza is delivered in a higher key, and it contains one of Sting’s favorite themes depicting a historical fall from grace:

The teachers told us, the Romans built this place

They built a wall and a temple, an edge of the empire

Garrison town

They lived and they died, they prayed to their gods

But the stone gods did not make a sound

And their empire crumbled, ‘til all that was left

Were the stones the workmen found

After “all this time” and effort spent in building their impenetrable stronghold (see Sting’s earlier tune, “Fortress Around Your Heart,” from his premiere solo offering The Dream of the Blue Turtles, for another of life’s lessons about breaking down walls); after all their prayers were offered up to false deities, the Roman Empire eventually gave way along with their physical surroundings. All was for naught, Sting tells the priests. He has juxtaposed the Romans’ dubious trust in their infallibility with the implausibility of our own creed:

Men go crazy in congregations

But they only get better

One by one

One by one…

——————————————————————————————————————-

(To Be Continued)

All songs were written and arranged by Sting © 1990 Magnetic Publishing, Ltd./Blue Turtle Music (ASCAP)

Copyright © 2013 by Josmar F. Lopes