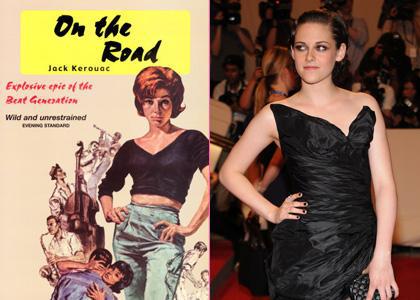

Undoubtedly, many of you will want to see Walter Salles’ forthcoming cinematic re-telling of On The Road. It’s also inevitable that your younger sisters will also want to see it since Kristen Stewart co-stars. This may leave you with the task of having to explain On The Road, and if so, here’s some advice.

Ever since I started teaching and writing about Jack Kerouac I have constantly been asked how I, as a feminist, could I possibly stand Jack Kerouac’s depictions of women in his novels. How could I possibly get past all the sexist language he used and scenes he wrote? To which I gave my now very practiced response: I can’t, I don’t, and what’s more, I wouldn’t even think to try.

Because, when it comes to literature, or any kind of writing for that matter, its all about how solid that writing’s terrain is for me, no matter how cracked or barren or shaky this terrain may be for a woman. The most rhetorically effective writing, I believe, is the writing that lures us out into the world, that inspires us to move past its pages, to venture out and see its terrain for ourselves and to perhaps, even write about it, create a new story of that terrain in our own vision, our own view. This, I believe, is what On The Road teaches us to be: literary and adventurous.

I am not, by any means, the first person to feel this way. Hakuri Murakami in his 2001 novel Sputnik Sweetheart articulates this idea much better than me (translated from the Japanese by Philip Gabriel):

“The first time Sumire met Miu, she talked to her about Jack Kerouac’s novels. Sumire was absolutely nuts about Kerouac. She always had her Literary Idol of the Month, and at that point it happened to be the out-of-fashion Kerouac. She carried a dog-eared copy of On The Road or Lonesome Traveler stuck in her coat pocket, thumbing through it every chance she got. Whenever she ran across lines she liked, she’d mark them in pencil and commit them to memory like they were the Holy Writ. Her favorite lines were from the fire lookout section of Lonesome Traveler. Kerouac spent three lonely months in a cabin on top of a high mountain, working as a fire lookout.

Sumire especially like this part: “No man should go through life without once experiencing healthy, even border solitude in the wilderness, finding himself depending solely on himself and thereby learning his true and hidden strength.” “Don’t you just love it?” she said. “Every day you stand on top of a mountain, make a three hundred sixty degree sweep, checking to see if there are any fires. And that’s it. You’re done for the day. The rest of the time you can read, write, whatever you want. At night scruffy bears hang around your cabin. That’s the life! Compared with that, studying literature in college is like chomping down on the bitter end of a cucumber.” “OK,” I said, “but someday you’ll have to come down off the mountain.”

As usual, my practical, humdrum opinions didn’t faze her. Sumire want to be like a character in a Kerouac novel, wild, cool, dissolute. She’d stand around, hands shoved deep in her coat pockets, her hair an uncombed mess, staring vacantly at the sky through her black, plastic-frame Dizzy Gillespie glasses, which, she wore despite her twenty-twenty vision. She was invariably decked out in an oversize herring-bone coat from a secondhand store and a pair of rough work boots. (And had, I’m certain) she had been able to grow a beard, she would have.”

So, in order to let your younger sister enjoy Kristen Stewart and try to inundate her with some feminist sensibility, remind her that maybe Kerouac was a little bit sexist, but the ideal he presented can be reclaimed from a feminist perspective: isn’t the ability to be like a character in a jack Kerouac novel one of the choices many, many feminists have fought for Sumire, for me and for you?