We are in Eysines, in an area known as Domaine du Pinsan, familiar to most these days for its sports fields, its swimming pool and its running path. At the base of a tree, a number of small plaques and potted flowers serve as an unofficial but poignant reminder of a tragic event that occurred here on December 21st 1987: the crash of Air France flight 1919 from Brussels to Bordeaux, and the death of its 13 passengers and three crew members.

The aircraft was an Embraer 120 turboprop operated by domestic airline Air Littoral for Air France, as part of a regular service connecting Bordeaux with Brussels and Amsterdam. On this Monday before Christmas, the weather was poor throughout much of Europe. After the outbound flight from Bordeaux touched down in Brussels at 10:37 Central European Time, the two-way Brussels-Amsterdam leg of the service was cancelled due to the bad conditions in the Netherlands. There was then a further degree of uncertainty when the Bordeaux-bound plane departed from Brussels at 13:30 because heavy fog back in Bordeaux had failed to lift as had been forecast; it was likely the flight would have to be diverted to Toulouse or Biarritz.

An Air France/Air Littoral EMB 120. Photo by Werner Fischdick, source: www.crash-aerien.news

However, captain Rémy Robert and co-pilot Guy Michoux (whose roles had been reversed, the co-pilot was “Pilot Flying” and the captain was “Pilot Monitoring”) were keen to return to their base in Bordeaux to avoid the obvious logistical complications of landing elsewhere, and they reached the area to the north of Bordeaux-Mérignac airport without any trouble. At this stage visibility remained poor and clouds were low (100 feet), so the crew requested to enter a holding pattern to the south. But, just as the aircraft was about to exit the flight path to enter the holding pattern, air traffic control reported an improvement in the weather conditions (the cloud base had risen to 160 feet) and, to air traffic control’s surprise, the pilots decided to revise their plans and immediately sought to re-join the landing route.At this stage, the plane was traveling faster and at a higher altitude than it should have been, and overshot the glide path to the airport, veering to the right of the designated trajectory. The pilots still considered they could rectify the path of the aircraft, deploying flaps and landing gear ahead of landing, but the plane’s descent was much too sharp, it was now well below the glide slope and radio contact with the control tower was lost. It was too late to recover and at 15:10, some 5,100 metres short of the runway, the plane struck some tall pines and crashed, burst into flames on impact and set fire to nearby trees. Everyone on board was killed virtually instantly.

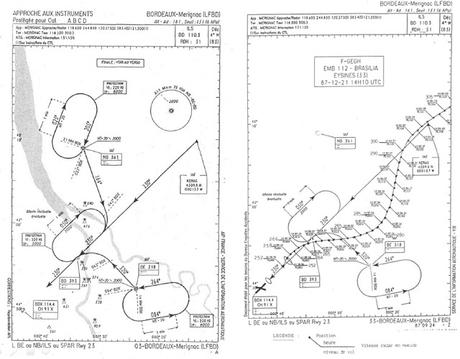

From the official report into the crash: on the left is the usual flight path from the north, over the Dordogne and the Garonne and on to Bordeaux-Mérignac airport. On the right is what flight AF1919 did, initially deciding to head towards the holding area to the south, and then switching back to the designated glide path, which it overshot by some margin to the right.

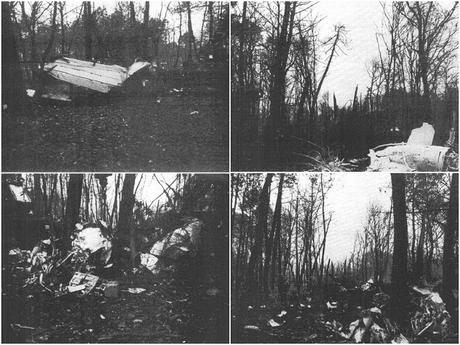

Emergency services soon arrived on the scene. They were met by the sight of windows blackened by the fire inside the fuselage, from which the wings had been torn. All 16 bodies - 11 men, four women (including air hostess Annie Suzineau) and a young girl - were recovered from the wreckage by the rescue workers, although it soon registered that the toll could have been far worse: the plane had crashed a mere 200 metres from a children’s day-care center where 30 toddlers were having their afternoon nap. The children were quickly evacuated from the premises.

Pictures taken at the scene of the crash as included in the official report into the crash. Top left: the tail of the aircraft; top right: one of the engines; bottom left: the front of the plane; bottom right: what remained of the cockpit.

A 37-page report (including a transcript of voice recordings of the final 30 minutes leading up to the crash) produced by France’s air accident investigation bureau (BEA, Bureau d'Enquêtes et d'Analyses pour la sécurité de l'aviation civile) was released some 18 months later and officially stated the crash was attributable to the mismanagement of the aircraft’s trajectory, due to a lack of vigilance on behalf of the pilots and poorly-coordinated tasks, such as monitoring altitude data and alignment with the on-ground instrument landing systems.Prior to that though, in the immediate aftermath of the accident, much finger-pointing and speculation had quickly emerged in local media. Regional daily Sud Ouest had run the headline “Les chauffards du ciel, les pilotes étaient ivres”, singling out the pilots as being both reckless and drunk. This latter claim was not initially backed up, and Sud Ouest issued a discreet correction/apology a few months later. Then again, in the BEA report, it was stated that tests showed the captain’s alcohol level was 0.35 grams per liter (today, the legal limit for pilots in Europe is 0.2 grams per litre), while the co-pilot’s blood was free of alcohol, but nothing more was made of this finding.

However, whether the pilots were under the influence or not, judging by a message pinned to the tree in Eysines, the families of the victims of the crash have neither forgiven nor forgotten their misjudged actions and decision-making. The text mentions "the pilots' incompetence" and quotes the verdict delivered by the Tribunal de Grand Instance de Paris in 1992, "an inexcusable error that caused the accident", before signing off "We do not forget. We do not forgive."

Finally, when researching this item Invisible Bordeaux uncovered an unexpected dimension which was undocumented in any of the contemporary media coverage or the official investigation report: one of the passengers on board the aircraft was the 22-year-old Philippe Deschamps, who was returning to his native south-western France from his new home in Brussels. He was set to meet up with his family to spend Christmas in Anglet, between Biarritz and Bayonne.

Didier Deschamps, pictured playing for Bordeaux (1990-91).

Picture source: Getty Images/Alain Gadoffre.

Didier Deschamps has only very occasionally spoken publicly about this pivotal and traumatic period in his family’s history, but in a 2015 interview with Canal+’s Michel Denisot he stated that “it’s something you live with. You can never forget. Life can be unfair, destiny can be cruel, and in this case it was very cruel and very unfair. You live differently, it hardens you. It was difficult for me personally, but I know that it was even more difficult for my parents, and it still is today even though many years have passed.”

Didier Deschamps talks candidly about the loss of his brother

[from BALAMED Youtube channel]

Click here if video does not display properly on your device.

A plane flies over Domaine du Pinsan, Eysines.

> Find it on the Invisible Bordeaux map: memorial to victims of 1987 plane crash, Domaine du Pinsan, Eysines> The full BEA report into the accident is available here: http://www.bea.aero/docspa/1987/f-gh871221/pdf/f-gh871221.pdf

> Cet article est également disponible en français.