If Passion juxtaposed a largely aimless narrative with another artform, painting, as a means of offering clues to its solution, First Name: Carmen uses music as its driving artistic counterpoint. Yet Godard does not simply swap out media but inverts the contrast: here the film has a much more pointed, understandable story, but the cutaways to the other artform prove murky and not easily explained. This, of course, can be explained by the different natures of classical music (wordless, united only by evocative compositional themes) and painting (more literal and, obviously, illustrative). Indeed, Godard uses music as an emphasis of emotion and mood, not so much clarifying an abstract story as deepening a coherent one.

If Passion juxtaposed a largely aimless narrative with another artform, painting, as a means of offering clues to its solution, First Name: Carmen uses music as its driving artistic counterpoint. Yet Godard does not simply swap out media but inverts the contrast: here the film has a much more pointed, understandable story, but the cutaways to the other artform prove murky and not easily explained. This, of course, can be explained by the different natures of classical music (wordless, united only by evocative compositional themes) and painting (more literal and, obviously, illustrative). Indeed, Godard uses music as an emphasis of emotion and mood, not so much clarifying an abstract story as deepening a coherent one.Sound is a key element in the film, with the audio track taking on the jump-cut properties normally associated with Godard’s images. This is nothing new; sudden fluctuations of noise and asynchronous play of sight and sound have been part of parcel of Godard’s cinema from the start. But there is something different about the director’s aural play here: where cut-up audio typically plays an intellectual, confrontational role in, say, the Dziga Vertov period, First Name: Carmen features an unorthodox use of fragmented sound to evoke the state of the characters and the overall tone of the action. One of the first lines spoken on the audio track, “It makes terrible waves in me and you,” is immediately followed with the sound of waves rolling onto a beach as seagulls screech. That gull cry is the most distracting noise of the movie, and like the sudden superimposition of the shrieking cockatoo in Citizen Kane, it may partly serve just to take the audience whenever it is used. But its restless, agitated squawk offers as crystalline and instant an insight into the spiky energy of this speaker as the beautiful yet thunderous sound of the ocean roiling underneath.

As the title suggests, First Name: Carmen adapts the Bizet opera. And as one should expect from Godard and Anne-Marie Miéville, it does not simply replicate the narrative. They hone in on Carmen as the foremother of the modern femme fatale, building off Passion’s overt linking of cinema to its artistic forebears. In repurposing the opera as a tale of bank robbers and wooed cops, Godard and Miéville stress how little they had to do to make the basic story modern. Maruschka Detmers embodies the timelessly ahead-of-their-time qualities of Bizet’s anti-heroine, and she even channels a bit of Anna Karina’s wild siren in Pierrot le fou. But the changing times can be seen in the way that classic Godard film differs from this one: Pierrot sparks with sexual tension, and its explosions of violence in some ways seem the result of that sexuality having no outlet due to censorship concerns. This film, on the other hand, exhibits nudity freely and features less violence. This freedom to simply cut to the chase likewise marks the most basic yet most profound revision of the opera Carmen, tossing out all the window dressing one had to invent to get around what such stories are truly, always about.

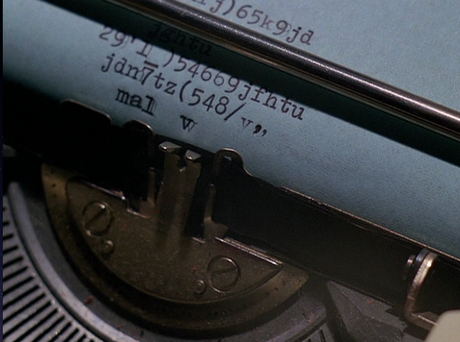

And yet, because that job proved so easy, the filmmaking pair pile two additional narratives on top of the Carmen reworking. Godard himself plays Carmen’s uncle, a washed-up director looking for inspiration, which gives him a reason to intersect with her own story. So does Carmen’s motive, her thefts ostensibly being used to pay for a film. But Godard uses his own thread as an entirely separate issue, one that allows him to take direct aim at himself. Puttering around a hospital, a disheveled Godard makes proclamations one might call pretentious were they not coming from the mouth of a clearly insane person. Many of those thoughts are the sort of spoutings Godard used to make seriously, not farcically: in a later scene, he absent-mindedly compares Mao to a great chef who fed all of China, the asinine nonsense of that statement openly ridiculing his own support of the disastrous Chinese leader’s policies. Even Godard’s schizophrenic, typewritten fragments make for humor, a jumble of random letters and numbers that give way to vague, emptily ponderous words like “unseen” and “unsaid.” Godard also plays himself as a leering lecher, furthering his reevaluation of his early sexism.

The other recurring element involves frequent cutaways to musicians practicing Beethoven’s late quartets. Their frustrated rehearsals match perfectly to the mood of what is happening around them: they attack their strings passionately during, say, the bank robbery Carmen and her cohorts carry out or, more amusingly, when the security guard she seduces during the theft, Joseph (Jacques Bonnafée in the Don José role), tries to get hard for her after they shack up together. Godard further complicates, and lightens, the quartet’s influence upon the visceral direction of the movie by tangling their playing with the aforementioned sound of cawing gulls, occasionally even laying that grating noise over images of the musicians running their bows over strings. The soundtrack even features several “hiccups” of dropped sound, a reminder of Godard’s love of flawed takes

If these distinct stories interact in ways literal and figurative, their collective effect is one of unexpected harmony. The film is frequently distancing, even absurdist, but it represents a key refinement of this new stage in the director’s career, a poetic breakthrough that makes for one of his most expressive works. In an abstract but poignant scene, Joseph warps his arm around a television set broadcasting only blue static as Tom Waits’ “Ruby Arms” plays over the shots of his backlit hand moving sensually over the flickering device. Godard has routinely mixed formally striking shots with analytical commentary, but the beauty of this shot transcends whatever message might be conjured by this image of a man tenderly caressing a TV. Building off the budding humanist streak in his previous two features, Godard now fully trades didacticism for evocation, even when he continues to pose his actors like models and mouthpieces.

Nevertheless, the most moving aspect of First Name: Carmen is the director’s restored faith in youth, or at least his renewed interest in them as a subject matter. In the wake of May ’68 and its failure, Godard’s films slowly drifted away from the revolutionary zeal that led to that event to the disillusionment of its aftermath. Ostensibly writing off that entire generation, Godard returned to them only to share in their defeat or jumped back even further to prepubescent children to look for some measure of hope. But Carmen and her young adult colleagues bring back some of the fervor of developed but idealistic youth; Carmen’s satirical court scene recalls the equally scabrous kangaroo session running through Vladimir et Rosa’s loony tribute to the Chicago Eight. Incidentally, that marked the last time Godard focused intently on Western young adults still waging a struggle. It seems altogether fitting that, as Godard’s parodic self-portrait stumbles about trying to think up a new, intellectually sound film, Carmen’s wildness and sensual immediacy effortlessly lay out an arresting, evocative narrative. The key difference between this and the director’s ‘60s gangster inversions that it recalls is the gender of the protagonist, a significant alteration that suggests that even in repurposing his early work, Godard will not simply repeat himself. When Detmers bluntly announces, “I feel like showing people what a woman can do with a man,” she challenges the director’s own early work as much as the changed social reality of the 1980s.