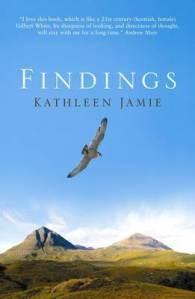

Given that the essay can be a performative little genre, the variety hall act of the literary world, I am compelled to grant enormous kudos to Kathleen Jamie for crafting something so lovely out of the perspective of the introvert. In the eleven essays that make up Findings, Jamie is on her own, often in the most distant and desolate locations in Scotland and the Hebrides, watching through binoculars or a telescope at small things far away, and meditating on the cycle of destruction and renewal that governs our lives no matter how hard we try to cover it up. Little things, finely wrought and deeply pondered become rich and complex in her crystal clear prose. These are quiet essays, even when the subject is her husband sick in hospital with pneumonia, she eschews the footlights of the stage to take her seat in the stalls and keep her calm, thoughtful viewpoint. It turns out to be a very illuminating one.

Given that the essay can be a performative little genre, the variety hall act of the literary world, I am compelled to grant enormous kudos to Kathleen Jamie for crafting something so lovely out of the perspective of the introvert. In the eleven essays that make up Findings, Jamie is on her own, often in the most distant and desolate locations in Scotland and the Hebrides, watching through binoculars or a telescope at small things far away, and meditating on the cycle of destruction and renewal that governs our lives no matter how hard we try to cover it up. Little things, finely wrought and deeply pondered become rich and complex in her crystal clear prose. These are quiet essays, even when the subject is her husband sick in hospital with pneumonia, she eschews the footlights of the stage to take her seat in the stalls and keep her calm, thoughtful viewpoint. It turns out to be a very illuminating one.

After the sensational hustle and bustle of so much of our contemporary literature, it can take a while to settle down into her voice. The first essay concerns a long, slow midwinter journey to Maes Howe on Orkney to visit a Neolithic burial tomb. Her hope is to witness the miracle of early architecture that is the sinking sun of the winter solstice illuminating the inside of the main chamber. But cloudy weather ruins the effect and the journey is made in vain. On first reading, I had the odd sense that nothing had happened, and the essay felt blank and inconsequential. But then the subtlety of Jamie’s writing took effect. Darkness has a bad press, according to Jamie, being relentlessly linked with evil, melancholy and death, but this is clearly a poorly informed view. Hoping to experience both pure darkness and pure light, she is thwarted; the night spent sailing to Orkney is full of the artificial brightness of human dwellings on the coast, whilst the visit to the tomb is spoiled by clouds. But multiple, tender ironies arise as Jamie makes her journey, from the surveyors and the brilliance of their 21st century lighting inside the burial chamber to the sound of Elton John being piped through the ferry, singing ‘Don’t Let The Sun Go Down On Me’. I began to realize that there was a gentle but insistant playfulness at work, wonderfully alive to the symbolic potential of the moment.

The essays are full of lovely touches that bring the natural world into harmonious parallel with the human one. In ‘Crex-Crex’, which concerns the near extinction of a once tremendously common bird, the corncrake, Jamie goes to the island of Coll to spy them in a nature sanctuary:

It’s not ideal weather for corncrake viewing. The sky’s overcast and threatens squalls, the breeze is too fresh. A wind above three knots, and the corncrakes don’t like to come out. They don’t like flying, don’t much care for wind and rain, don’t want to be seen in public – the kind of bird who’d want to be excused games.’

In ‘Skylines’, Jamie ascends Edinburgh’s Calton Hill with a telescope, intent on paying close attention to the tops of buildings in the city, the weathercocks, stars, crosses and antennae of different ages, most of which are ignored or invisible to the passers by on the streets. Again I feared there might be too little to hold my interest for the duration, but I underestimated the clarity of Jamie’s vision, her eye for the intriguing:

There is a woman, though, who sails aloft on the dome of the Bank of Scotland HQ. The bank stands at the top of the Mound, bearing down upon the prosperous New Town as though to remind it of exactly who’s boss. In Scotland’s capital city, Fame faces firmly south. Green with verdigris – not an unbecoming shade – and draped in robes, she holds in her hands two laurel wreaths. She is about to cast them away, to bestow them onto some unsuspecting pedestrian far below. For all the grandiose Baroque nonsense beneath her bare feet, Fame stands as stylish and bored as a cruise passenger playing quoits.’

This is the strength of Jamie’s writing, the simplicity of voice married to the richness of her perspective. In my favorite essays, ‘The Braan Salmon’ and ‘Sabbath’, there is the most delicate thread of a theme running through the observations. Watching salmon leaping upstream – and watching those watching them do so – Jamie is forced to ask uncomfortable questions about the inspiring image of tenacious nature at work, when it becomes clear that the river has been tampered with to prevent the salmon returning to their breeding grounds. And in ‘Sabbath’, she juxtaposes a summer of difficult family events – her young daughter’s head wound, her mother having a stroke, her grandmother needing to be put in a home – with a few days of pure isolation spent walking to clear her mind before the university term starts. Would it help, she wonders, if we all were forced once again to respect a Sabbath, a day in which we did nothing but allowed the stirred up emotions of life to settle?

Kathleen Jamie’s publisher had all sorts of difficulties deciding how to categorise her essays, which made me cheer because being able to put a book firmly on a shelf in a shop does not necessarily do anything for the quality of the book, or the reader’s delight in reading it. But essentially, these essays are about the way we interact with nature, our inevitable thumbprint on its dead and disappearing elements, the amazing beauty and grandeur we can find if we take the time to look, the pleasure it bring us to see ourselves and our habits reflected in the natural world. If there isn’t a category for that already, then perhaps there really ought to be one.