Fijian coat of arms. The motto translates to “Fear God and honor the Queen” (Wiki Commons/Simi Tukidia)

My strange fascination with cannibalism began while I was studying history in graduate school. In a book whose title I have since forgotten (which might indicate why I quit grad school altogether), I read that Nelson Rockefeller’s son Michael Rockefeller disappeared when he was 23 years old and that he was possibly cannibalized in Melanesia. At the time, I didn’t know which came as a bigger surprise: that the young Rockefeller was most likely devoured by other human beings or the fact that it happened in 1961, which still seems relatively recent for people to have been eating each other.

Of course, most people in so-called “civilized” society are under the impression that cannibalism is a thing of the past. And I don’t mean “cannibalism” metaphorically or as some kind of fetishistic anomaly. I mean it as a religious practice in which one individual literally consumes another as part of a ritual to ingest an enemy’s knowledge, courage, and power.

Yet while cannibalism is a full-blown taboo in the Western Hemisphere, it’s also been a standard practice in another part of the world for generations. The area where Rockefeller disappeared lies just south of the equator and west of the international dateline, a subregion of Oceania that’s also home to New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, and Fiji, aka the “Cannibal Isles.” But because cannibals haven’t kept written records of their practice, it’s almost impossible to find out when it stopped, if at all.

For instance, the Korowai tribe in Papua New Guinea supposedly still practices cannibalism today, which prompted a 60 Minutes crew to investigate. After the show aired in 2006, however, people claimed that it was all a hoax in an effort to drum up tourism. Yet what kind of a weirdo would go somewhere specifically because there might be cannibalism? As it turns out, I would.

Port Denarau in Viti Levu (Photo: Tanja M. Laden)

When I recently found myself on a romance-themed press trip to Fiji, cannibalism was the first thing that came to mind. Truthfully, I don’t usually write about romance: I tend to gravitate toward the offbeat, lesser-known aspects of culture. Rather than covering UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Croatia, I wrote about the Museum of Broken Relationships in Zagreb. In lieu of of documenting the Iceland Food and Fun Festival, I canvassed the Icelandic Phallological Museum and took an afternoon crash-course at the Icelandic Elf School. And instead of covering the well-trodden literary landscape of San Francisco, I paid a visit to the Antique Vibrator Museum. So during my time in Fiji, while my colleagues were researching romantic getaways, destination weddings, and honeymoons, I was interviewing a Bouma tribesman and elder storyteller about his cannibal ancestors.

I suppose I should have felt guilty that I wasn’t writing about the romantic topics the nice people at Tourism Fiji hoped I’d cover when they sponsored my entire trip. But one look at my list of published stories and they’d have seen that romance wasn’t exactly my beat. Even so, I was feeling a bit awkward about how I’d tactfully pursue the sensitive topic of cannibalism while I was supposed to be focusing on boutique hotels, beach-side weddings, and cloying cocktails. But the ironic truth of the matter was simply that my heart wasn’t into writing about anything sentimental. After all, to most people, Fiji is still very much an unknown part of the world, and I wanted to write about something equally unfamiliar.

Taveuni, Fiji (Photo: Tanja M. Laden)

I finally resolved to write about cannibalism once I learned that we’d be visiting the island where the last act of cannibalism was recorded: Taveuni. Also called the “Garden Isle,” Taveuni is the third largest island in Fiji, with indigenous people comprising about 75% of the population. If anywhere, this would be the place where someone could tell me for certain if and when cannibalism actually ceased in Fiji.

Immediately after our group arrived in Taveuni, I told our driver Babu that I wanted to talk to people about cannibalism. As the rest of the journalists departed to have banana leaf-wrapped massages, Babu took me to interview Josef Rapuga, a 52-year-old tribesman of the Bouma waterfalls and part of the chief’s clan in the Mau community of Taveuni. Per local custom, I first needed to buy two bundles of kava root at $20 each, plus a sarong and a pack of Benson & Hedges Ultra-Lights to present as gifts to the 55-year-old Mau chief, Joe Turaqacati, before I asked the chief whether I could “borrow” Rapuga for an interview. After a small, slightly awkward ceremony in which the chief’s tribal council accepted my gifts, I was officially permitted to ask Rapuga, the clan’s official storyteller, anything I wanted to know about cannibalism, with the help of a translator.

Kava Root (Photo: Tanja M. Laden)

Back at the picturesque Taveuni Palms resort where my group was staying, Rapuga and I sat down to discuss how cannibalism first became a ritualized practice in Fiji when European settlers arrived in the 19th century. He told me Fijians would eat people from other “races” to protect their property and as a form of revenge. When hunting down and eating their enemies, locals used a stone axe (matau vatu) and a spear (moto), along with an eye-gauger (totokia) and a sea (pronounced say-ah), which was like a brain-smasher. Then they’d eat their victims with a special cannibal fork called an ai cula ni bokola.

After Fijians killed their enemy, they’d drink the blood in order to become more powerful, because, as Rapuga noted, “the blood runs through the entire body.” The corpse would then be divided into portions, with the chief eating the heart and brain because everyone believed he’d literally “absorb” his enemy’s knowledge and courage. Next, a village priest would perform a ritual to one of the gods and the tribe would gather for a big celebration under the moonlight, dancing with their spears around a bonfire while the feast was cooking.

Josefo Rapuga, tribesman of the Bouma waterfalls and member of the chief’s tribal council in the Mau community of Taveuni (Photo: Tanja M. Laden)

Since the chief said that any question was OK, I asked Rapuga if he knew how humans tasted, and whether cannibals would serve the meat with any side dishes like vegetables. He said humans tasted like pork but sweeter, and that they’d cook the meat in an earth oven and serve it with breadfruit and yams.

When I questioned how he knew all this, Rapuga said nobody told him, but that he had somehow known it all along. He claimed that the last person to eat another human being in his family was his great-grandfather, and that Rapuga himself received all his knowledge about cannibalism almost immediately after his own father died in 1998, without anyone ever telling him anything directly.

According to Rapuga, cannibalism officially stopped in Fiji in 1844, when a man from Tonga waged war against the Bouma clan in a place called Kai lekutu, or “place of the forest people,” in what is now Bouma National Heritage Park. After the man was killed, the first thing the tribesmen did was take out his heart, which they took to a hilly area they named Tavuki, the regional word for “spit,” because that’s where they’d roast the meat on a spit.

Cannibal forks on display inside a hotel room at the Westin Denarau Island Resort (Photo: Tanja M. Laden)

When Christian missionaries arrived in Fiji soon after, cannibalism supposedly ended, but not before a Methodist missionary from England named Reverend Thomas Baker was killed and eaten in 1867 in the village of Nabutautau on Fiji’s largest island of Viti Levu. After Baker’s death, local Fijians noticed that their soil suddenly became infertile and all their crops died, so they began to believe other Christian missionaries who warned the cannibals that they were condemned because of their past. This led Fijians to make a series of three official apologies to Baker’s descendants, the most recent one in 2003. After that, Rapuga explained, “Their soil became fertile again, which to them, confirmed the idea that they were cursed.”

Rapuga said that the last act of cannibalism in Fiji was in 1844, but acknowledged Baker’s murder, which happened more than two decades later in 1867. He also told me his great-grandfather participated in cannibalism, but it’s highly unlikely his relative lived so long ago. Finally, Rapuga said cannibalism started with European settlers and ended with missionaries, yet both groups arrived in Fiji around the same time during the 19th century, which sounds like cannibalism ended almost before it began. But rather than belabor the dates, I asked Rapuga whether he thought it was possible that cannibalism was still happening in Fiji today. He just smiled and said that he believes it’s finished. “Our people are going to church,” he said, and that was the end of our interview.

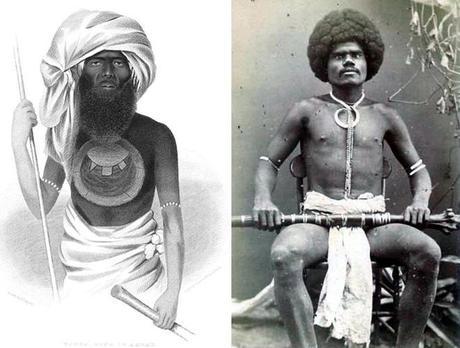

Left: Ratu Tanoa Visawaqa, King of Bau 1829-1832 and 1837-1852 (Source: David Rumsey Map Collection/Wiki Commons) Right: Fijian mountain warrior Kai Colo, 1870s (Source: F.H. Dufty/Wiki Commons)

By nature of the practice itself, cannibalism in Fiji was rarely recorded, so how is it possible that the last act of cannibalism was? Fiji has 1166 tribes and 332 islands (less than half of which are “permanently inhabited”), so how do we really know if it still isn’t happening in the interior regions and other places where westerners don’t honeymoon? The truth is, we don’t.

Discouraged over my dead-end interview with Rapuga (and a little chastened over missing a banana leaf-wrapped massage), I believed my cannibalism story had reached a dead-end, too. But then shortly thereafter, in one of those cosmic coincidences that can only be described as serendipity, I met Katie Selachii* during a snorkeling expedition on a tiny island between Viti Levu and the small island of Yasawa.

Originally from the United States, Selachii has been living in Fiji for nearly 20 years, operating her own local business renting diving equipment to tourists. We immediately hit it off, and she seemed intelligent, articulate, and very down-to-earth. When she asked me what I was doing in Fiji, I told her that I was trying to write a story about cannibalism. Without missing a beat she asked, “Did you know that cannibalism is still happening in Fiji today?” Then she handed me her business card and told me to call her.

So once I returned to Los Angeles, I did.

Islands between Viti Levu and Yasawa (Photo: Tanja M. Laden)

“Basically, I do have a good friend here who has eaten someone,” Selachii told me over the phone from her office in Fiji. “He kind of told me the whole story.”

Selachii said that as long as she was able to speak under the condition of anonymity, she was happy to talk to me. Of course, it occurred to me that what she was about to relate to me might not be true, but my gut told me not to doubt her sincerity. In the end, I just couldn’t believe she’d lie about something so detailed, and as it turned out, relatively in keeping with what Rapuga already told me about his own relatives.

When Selachii first asked me to call her, I realized that maybe this woman needed to tell me her story almost as much as I needed to hear it, so I let her speak.

She began telling me about her her friend Marcus*, a 41-year-old native Fijian who cannibalized someone 11 years ago. Selachii said Marcus and Dinesh*, a man from another tribe, were fighting over the same woman when the feud escalated and Dinesh attacked Marcus in the middle of the night — threatening to kill him and eat his entire family. Marcus believed his enemy would actually follow through with his threats, so rather than allowing himself to become a victim, Marcus decided to come up with a plan to kill Dinesh and eat him first.

“He’s one of the most traditional Fijians I’ve ever met,” Selachii described Marcus, “So it doesn’t surprise me that out of all the people I’ve met here, he would be the one to be a cannibal.”

Selachii said Marcus knew when Dinesh would go out fishing in an outrigger canoe, and because they were in a fairly isolated area, Marcus was able to murder his rival without anyone around. He used a club to kill Dinesh, then brought him to a remote beach and cut him up into smaller pieces before Marcus burned the body of his enemy and ate him.

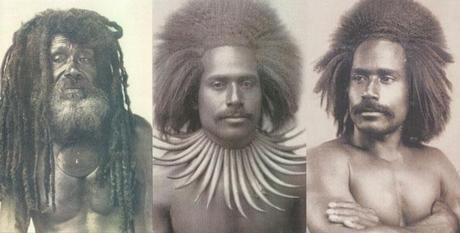

Fijian Cannibals (Courtesy Fiji Museum)

“He said that his vu were with him, guiding him the entire time,” Selachii said. “The vu are your ancestral spirits: all of your relatives that have already passed. They are always there, watching you and guiding you.”

While Selachii said nearly all her Fijian friends believe in vu, Marcus maintained that he could actually see his on the beach while he was getting ready to eat his victim. In fact, his vu provided detailed instructions on how to eviscerate and consume his nemesis.

Selachii asked Marcus whether he knew of other cases of cannibalism, and he admitted that it doesn’t occur every day, but he knows for sure that it’s still happening, especially in secluded areas of Fiji like the relatively uninhabited island where he lived.

Once Marcus killed and ate Dinesh, Selachii said her friend couldn’t sleep for years because he was constantly haunted by visions of what he did. Eventually, Marcus started drinking heavily and even went through a suicidal phase. Since then, it’s become easier for him, but not much.

“It basically fucked him up for the rest of his life. He has to live with it every day,” Selachii said. “But it’s this weird duality, because one part of him, the western side, is totally messed up about it and is horrified that he did this. Then there is this other side — and I can’t explain it — that doesn’t have remorse. Like it’s this sort of ancestral idea of, ‘We’re supposed to do this. This is who we are. This is a part of our culture.’”

Cannibal souvenirs at Nadi International Airport (Photo: Tanja M. Laden)

By all appearances, cannibalism has always had a highly spiritual purpose within the context of an intensely personal ritual between a warrior and his victim, which is why it’s historically undocumented. Yet cannibalism remains deeply ingrained in Fijian local communities as part of its cultural heritage and narrative history. At the Nadi International Airport in Fiji, for instance, stores actually sell replicas of cannibals forks and cute little “cannibal man” souvenirs, so it doesn’t seem as though Fijians are exactly ashamed of their heritage. In fact, it looks like they’re proud of it.

Yet while native Fijians are still negotiating the reality of their own cannibal past through their ancestors, both dead and alive, Christian missionaries forever changed Fijians’ concept of revenge — shifting the paradigm to forgiving their enemies instead of eating them. But the missionaries also introduced Fijians to the idea of guilt, which doesn’t appear to have stopped cannibalism from happening in Fiji — it just makes it less bearable for the descendants of cannibals to accept today.

As Selachii and I wrapped up our conversation over the phone, I thought about the incredible story she had just told me. What struck me most about my reaction was the lack of one. I wasn’t as stunned as I felt I should have been. I questioned my indifference, working up a slight neurosis over my nonplussed attitude upon learning that cannibalism is still happening. But then, wasn’t this the answer I was seeking all along? Perhaps, just like Rapuga, I “knew” cannibalism never really ended without having anyone tell me, and Selachii’s story just confirmed it. Maybe an unexplained part of me was always aware that cannibalism is still a reality, and I simply needed proof. In the end, it’s possible this unusual piece of knowledge came from my own vu, just like the ones who taught Marcus how to eat his enemy.

* names have been changed per request