Image from http://www.nbcnews.com

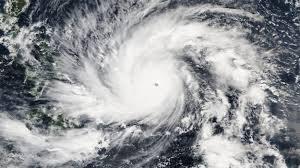

“Typhoon Hagupit hit the Philippines within the first week of December 2014, leaving no less than 27 dead and multiple locations in the islands of Luzon and Visayas in a state of calamity.”

Look up any news article on the recent Typhoon Hagupit and you’re bound to read something along these lines.

These words may be descriptive of almost any typhoon that has caused similar damage to countries in Southeast Asia. Although they are nothing short of the truth, the monotony of such descriptions is precisely what makes it difficult for some to fully empathize with what the onset of a typhoon might mean for countries like the Philippines that are still recovering from Typhoon Haiyan, also known as the strongest typhoon to ever be recorded in history.

One might initially think that this difficulty to empathize would be found in a small percentage of people in nations far away from the Philippines who are unable to bear firsthand witness to the utter destruction caused by natural disasters.

But even in the light of Typhoon Yolanda and the recent Typhoon Hagupit, this difficulty to empathize is no less likely to be found in places none other than the Philippines itself; not only for lack of exposure but also as a result of sheer indifference.

In the Philippines, the gap between the rich and the poor is larger than one might think.

Growing up and studying in an international school my entire life, I have never been surrounded by children whose families fall under the World Bank’s ratio of the 25.2% of the Philippine population that earns less than the minimum amount of money needed to fulfill basic needs. These families are those that feel the strongest blow of super typhoons and even heavy rains that can serve as a threat to their fragile homes and all that’s necessary for their survival.

I live nowhere near the city of Tacloban where Typhoon Yolanda so strongly demanded its presence to be felt in November 2013. I am in no way entitled to speak for those in areas strongly hit by these typhoons, as I have never felt the full blow of these natural disasters myself. I am also in no way entitled to exclude myself from the following statements I am about to make in the light of the typhoons that took place towards the end of this year and the last.

November is the month before midterms that marks the onset of rigorous homework, studying (or lack thereof), and multiple assessments to be completed within a span of four weeks. For privileged students, the immediate response to the mention of an incoming typhoon would be to heave a sigh of relief and wait for any mention of the cancellation of classes. These can last from two days to even a week after a typhoon first makes it presence felt. Such news would guarantee deadline extensions and extra days for us to relax and study before exams take place and our first semester report cards are released.

We are fully aware that in no way will we be physically affected by the events to come. The most these super typhoons will do is to induce minimal flooding into our homes and let water seep in through our windows; nothing we can’t prepare for in advance. Although our electricity and Internet access may be cut off for a few days, the same cannot be said of our access to food, shelter, and clean water.

It’s only after a while that this blatant selfishness and indifference is replaced with guilt. Although some of us tend to act on these feelings by arranging mission trips and packing relief goods, others choose to carry on with their lives without pushing themselves to be critical of what these disasters might imply for the rest of the population that did not grow up privileged.

Although the effects of the Typhoon Hagupit were not as strong as those of Typhoon Glenda and more so of the cataclysmic Typhoon Yolanda, they were enough to remind me of the apathy and detachment that can be seen in the privileged youth more than in anyone else when these types of situations arise.

Our privilege will never serve as an excuse to be indifferent and unaware of both domestic and foreign events of great significance that extend far beyond the scope of our sympathies. It may be difficult to drop everything in the middle of exams and in the thick of the hustle and bustle of the last few weeks of any school semester. Yet we must push ourselves to translate our sympathies into concrete actions that, no matter how grand, can make a positive impact on those who lead everyday lives that we may not even be able to imagine ourselves in. Acts even as simple as packaging food, clothes, toys, and unused items around our homes to be sent to areas of extreme devastation will serve as great help for those who live in areas shattered by natural disasters.

We must resist the urge to be indifferent in times of ruin and obliteration that are unjustly induced by nature, and even those that are unjustly induced by mankind.

Just because it’s not happening to us doesn’t make it any less devastating or unimportant to think about, especially on stormy days that we would otherwise be spending with all members of our family in the comfort of our own homes if not shivering through heavy winds and watching the heart of all that we have come to know get torn apart right in front of us.