Two interlocking quotations from feminist theologians I've been reading lately--Delores S. Williams and Ivone Gebara:

Delores S. Williams, Sisters in the Wilderness: The Challenge of Womanist God-Talk (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 1993):

The fact remains: slavery in the Bible is a natural and unprotested institution in the social and economic life of ancient society—except on occasion when the Jews are themselves enslaved (130).

Ivone Gebara, Out of the Depths: Women’s Experience of Evil and Salvation, trans. and intro. Ann Patrick Ware (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2002):

Theology has never considered discrimination because of skin color to be suffering. European theologians have never undergone this suffering as their own or as a part of Christian ethics or as a fundamental element in the quest for justice. The existence of dark-skinned slaves, men and women alike was historically of no great concern to Christian ethics (39).

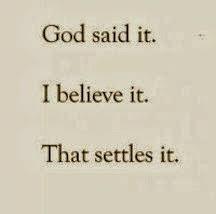

Both observations have direct connection, it seems to me, to the current debate about whether rejecting same-sex marriage is biblically and morally legitimate, while it was biblically and morally illegitimate for some of our forebears to reject racial integration in the 20th century. Many opponents of same-sex marriage want to maintain that they're now reading the bible "correctly" as they argue against same-sex marriage, while those who used the bible in the past to support slavery and then racial segregation were using it illegitimately.

As Delores Williams points out, the entire Judaeo-Christian bible is imbued with slavery. Opponents of same-sex marriage who argue that the weight of scripture and of Christian tradition lies heavily against acceptance of homosexuality do not want to recognize that the weight of the scriptures (and of Christian tradition) is even more strongly freighted on the side of approving of slavery.

The worldview which takes for granted that slavery is "a natural and unprotected institution" (except on the occasions when the Jewish people are enslaved): Christian churches and cultures eventually made a difficult but decisive decision to judge that worldview morally defective--no matter what the bible says. Anyone arguing that scripture and tradition have "always" seen homosexuality as morally wrong needs to take this historical turn into account, especially when the handful of biblical verses that can be cited to show that the entire bible is obsessed with the notion of homosexuality and with condemning homosexuality is so tiny in comparison with the wealth of verses that can be cited to show that the bible supports slavery.

And then there's Ivone Gebara's reminder that the entire tradition of Christian theology--the whole enterprise--can be morally blind, morally defective, especially insofar as it simply ignores the suffering of sectors of the human community. As she notes, because European theologians have historically not had to cope with the misery inflicted on some human beings due to the pigmentation of their skin, European theology--which is to say, the whole history of Christian thought up until recently--acted as if such suffering did not exist. Was beneath notice . . . .

And so "the" tradition has nattered on for centuries about justice (and love, and mercy) without paying the least bit of attention to the significant--the deep--injustice that happens when some human beings force other human beings into bondage, depriving them of control over their lives and futures, treating them as chattel. "The" tradition can be wrong.

It can be morally obtuse. It can ignore clear, obvious suffering that is outside the scope of those who write its classic works, who think its big thoughts.

It can act as if women are not there, don't exist, don't deserve attention, when those who write the classic works and think the big thoughts are always male. It can play invidious games with the lives of those who are gay and lesbian when it pretends that none of those writing the classic works or thinking the big thoughts is anything other than heterosexual--that gays simply don't exist.

Those now resisting the full humanity and full inclusion of gay and lesbian human beings into the human community will almost certainly be seen at some point down the road as every bit as morally obtuse, morally wrong--every bit as bigoted--as those who were once just as certain as these contemporary bigots that the weight of the bible and Christian tradition stood on their side as they resisted the abolition of slavery, the racial integration of society, the extension of rights to women.

Those folks, too, after all, insisted that they weren't in the least bigots, and that they had landed on "the" right interpretation reading of the bible. And that the whole weight of Christian history and practice supported them . . . .