Rossellini makes something miraculous, a work dense with political intrigue and historical upheaval, yet one that works primarily as an evocation of the Renaissance’s greatest achievement: the synthesis of religion, politics, science and art. Yes, money finds new and lasting use as a political weapon, but it also supplies artists with the patronage they need to improve society using techniques traceable to breakthroughs in science. Cheap costumes and plywood sets feel real as Rossellini stages his shots like contemporary paintings, playing into our visual conception of the Renaissance as he celebrates the nuts and bolts that made it possible. Possibly the greatest thing ever made for television.

2. French Cancan (Jean Renoir, 1955)

The affirming companion piece to The Red Shoes’ despairing view of the inescapable need for the artist to create. Every shot so painterly that I sometimes mistook actual paintings in the background for people, but the careful composition is disrupted exuberantly by dance. Renoir admits the Sisyphean nature of art and performance, always pushing toward something unattainable, then he finds the humor and fulfillment in it. As with Renoir’s television film, the artifice captures the world better than reality.

3. The Shop Around the Corner (Ernst Lubitsch, 1940)

Boy is the Lubitsch touch on display here, perfectly constructed to be light enough to feel spontaneous and merely observed at every turn. A film so warm that even a suicide attempt can be framed as a joke without being macabre, and nothing ever turns out as expected. That’s true even when the lovers are fully revealed to each other, the illumination of their love ironically played out in a room where all the lights just got turned out. I am still gingerly moving into Lubitsch, but I think I loved this one even more than Trouble in Paradise, something I did not think would happen.

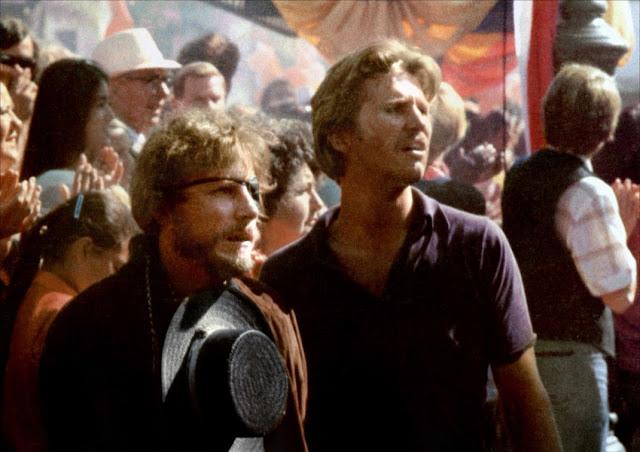

4. Cutter’s Way (Ivan Passer, 1981)

A requiem for New Hollywood’s post-’Nam, post-Watergate concerns that rolls everything of the past decade into a taut neo-noir. Paranoid thriller, traumatized veteran drama, existential anomie, raw performances, soft lighting, etc., etc. John Heard thrills as the maimed vet Cutter, so desperate to get revenge against his injuries that he latches onto a local corporate tycoon as a proxy for the military-industrial complex that sent him off to be ruined. Bridges and Eichhorn have the quieter, in some ways more powerful performances, and I feel I will likely pay more attention to them on subsequent viewings, which I can’t wait to give this.

5. The Flight of the Red Balloon (Hou Hsiao-hsien, 2007)

Flight plays upon Hou's mastery of space, blocking and mise-en-scène, so perfect in its craftsmanship yet so lyrical in its gentle, illusory spontaneity as it occasionally breaks off to follow the red balloon or even just cheekily frames red lights, blurred taillights, etc. as acceptable substitutes. As thrillingly, Binoche throws that formal rigor into disarray; her frayed-nerves basket case adds an element of disorganized mania to what is already vaguely melancholic, yet her vivacious, unself-conscious nature feeds into the ineffable sense of invitation Hou codes into his alienated characters.

6. Goodbye, Dragon Inn (Tsai Ming-liang, 2003)

An elegy for the cinema as a paradox of communal solitude, slowly being replaced by full loneliness of home theater viewing. Halfway in, the first line of dialog lets a character know the theater is haunted, an unnecessary statement in a movie in which everyone seems to be a ghost. Even the actors in the movie being shown come to watch their past selves. Extreme long takes of wandering ticket lady, empty seats and the film at hand communicate both loss of a way of film viewing and a quintessential element of its magic.

7. Forbidden Planet (Fred M. Wilcox, 1956)

Trades Cold War fears for Freudian psychology made manifest through alien technology. Nuclear power is invoked only in the extreme as a means of quantifying the power of imagination, and the id can overpower even that. Also features the greatest matte paintings I’ve ever seen, creations of obvious flatness yet involving depth perfect for a loose telling of one of Shakespeare’s most self-reflexive plays.

8. Shoot the Piano Player (François Truffaut, 1960)

I’ve neglected Truffaut for Godard, Rohmer and Rivette, but boy was this a delight. A mash-up of conflicting genres and moods, often within the same shot, makes for a jazzy riff on various forms of disreputable movies made prestigious through Truffaut’s light but ordered frame. Takes Hawks’ maxim, “Three great scenes, no bad ones” to heart, resulting in a movie that feels cobbled together of nothing but great scenes. And when that’s the case, who cares if the plot zigzags about to accommodate them?

9. Track of the Cat (William A. Wellman, 1954)

William A. Wellman, perhaps the premiere metteur en scène, produces a work that might have gotten him auteur status if he did more like it. A monochromatic palette makes Mitchum’s coat stand out as much as the girl’s in Schindler’s List. Claustrophobic interiors, shot in draining chiaroscuros, conjure repressions of all sorts, eliciting an implosion that suggests the panther may be a kind of divine reckoning. That it ultimately becomes the agent of the family runt's ascension is a regrettably prosaic conclusion for a film in which one hunter finds himself without food but with a collection of posthumous Keats, which he burns less for the warmth than to destroy the haunting prediction of his own demise.

10. The Yards (James Gray, 2000)

Jaundiced color timing matches its view of post-industrial commerce, operated along lines of corruption instead of production. Despite operatic framing of this, existential trap of ex-con who finds legit world holds crimes of its own, even incestuous desires, Gray never uses his characters as symbolic props they way they can be in The Godfather. Someone on MUBI mentioned Rossellini in relation to the film's ending. Considering everything that comes before looks like a more personal, modestly scaled Cimino, a nod to another modernist master of the cinema seems about right.