I’ve written about William Faulkner (1897-1962) as my favorite novelist. A Mississippian, his books were all set there, between Civil War times and the early 20th century. The characters and their stories ain’t pretty. Yet the books exuded a love for humanity. I chose a Faulkner quote as the epigraph for my Optimism book.

Though the novels did include Black characters, they never really get into the race issue. Indeed, all the nasty stuff was white-on-white. The situation of Southern Blacks was a background fact, but so unremarked there seemingly might have been no such situation. So much a “given” of Faulkner’s milieu that it required no acknowledgement. Or maybe it just wasn’t what he wanted to write about.

I recently read a Modern Library volume titled William Faulkner – Essays, Speeches & Public Letters. One fairly long piece discusses the American dream, where the individual is “free of that mass into which the hierarchies of church and state had compressed and held him.” But in our sleep “it abandoned us . . . what we hear now is a cacophony . . . babbling only the mouthsounds; the loud and empty words which we have emasculated of all meaning whatever — freedom, democracy, patriotism.” A sickness that “goes back to that moment in our history when we decided that the old simple moral verities over which taste and responsibility were the arbiters and controls, were obsolete and to be discarded.” And “Truth — that long clean clear line . . . has now become an angle, a point of view having nothing to do with truth nor even with fact, but depending solely on where you are standing.”

All cogent about today’s Republicans, I thought. Though written in 1955. And what got Faulkner’s bile boiling? Some magazine had the temerity to run an article about this Nobel laureate against his wishes!

But some of these pieces do address race matters Faulkner sidestepped in his novels. For a Mississippian of his era, he was on the enlightened end of the spectrum. But that’s not saying much.

Faulkner truly loved the place, and not just the scenery. He expressed love for its people, culture, and traditions. Now, I believe most people are mostly good. But unfortunately susceptible to shaping by the culture embedding them. I’m sure Faulkner could have expatiated on the virtues in Mississippi’s culture and traditions. But that would omit key realities.

He actually had nothing to say about slavery. Yet did imbibe the South’s “Lost Cause” mythology, that there was something noble in their fight, though what, exactly, is never very clear. He definitely considered the Northerners the bad guys, unjustified invaders. That too elides much historical reality.

Faulkner actually endorsed racial equality. But not right away. Urging the civil rights movement — then just starting — to go slow. He was “strongly against compulsory integration.” Seemingly, he didn’t want Southern racists to gain the sympathy that underdogs accrue. Saying they’d come around eventually. (But after a century . . . )

In 1931, a Memphis newspaper published a Black man’s letter endorsing a Mississippi anti-lynching organization. Noting that there’d never been a lynching before Reconstruction. Faulkner found it needful to reply.

He explained, “there was no need for lynching until after reconstruction days.” (He suggests the influx of Northerners then was responsible for lynchings.) And asserted that “Blacks who get lynched are not representative of the black race, just as the people who lynch them are not representative of the white race.” Indeed, he believed anyone lynched must have done something wrong, to provoke it.

Faulkner did state, “I hold no brief for lynching.” But (my paraphrase) — it’s just one of those things. He said a lynching “requires a certain amount of sentimentality, an escaping from the monotonous facts of day by day.” And if a few Blacks suffer thusly from “white folks’ sentimentality,” he adduced a convoluted scenario of such sentimentality indulging a Black debt cheat. Also mentioning a Black man supposedly living for fifteen years on public charity, impossible in any other country — which he said is why they have no lynchings. Then he made fun of foreign press accounts of U.S. lynchings.

His final paragraph conceded “that mob violence serves nothing.” Yet ended saying, “Some [people] will die rich, and some will die on cross-ties soaked with gasoline, to make a holiday. But there is one curious thing about mobs. Like our juries, they have a way of being right.”

Now, I had to consider the possibility that this ostensibly execrable piece was actually a wicked satire of people who excuse lynchings, to expose their bad thinking.* But no, this was 1931 Mississippi. With its distinctive people, culture, and traditions to which Faulkner was so attached.

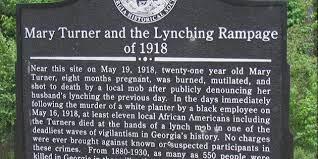

What the post-Civil War Reconstruction period introduced was the idea of Black people having rights. Lynchings were one way whites fought that. The point was not to punish Black crimes, but to terrorize any Blacks trying to assert any rights. To keep them “in their place.” Accusations were mere pretexts. A high proportion of lynching victims were completely innocent. There were thousands; more in Mississippi than in any other state.

Yes, lynchings did become festive “holidays.” Revealing they had nothing to do with justice, they were celebrations of white supremacy. And — mostly accompanied by hideous torture — revealing the inhuman cruelty of the perpetrators’ “culture and traditions.”

Mobs “have a way of being right?” How about the one that lynched Mary Turner, eight months pregnant, in Georgia on May 19, 1918. Her husband had been lynched the day before — one of seven innocent Blacks lynched for supposed complicity in the death of a white farm owner who had abused them. Mary Turner’s transgression was to protest against her husband’s murder. For that — to teach a lesson — a mob bound Mary’s feet, hanged her upside down from a tree, threw gasoline on her, and burned her clothes off. Then took a butcher knife to cut her baby from her body; one man crushed the crying baby’s head with his foot. Finally Mary was killed by a fusillade of bullets. No one was ever charged with a crime.

“Sentimentality?” Culture and tradition, Mr. Faulkner?

I can’t say I’ll never read Faulkner again. But it will be with lessened pleasure.

* To be sure here, I did some googling, and turned up a master’s thesis discussing Faulkner’s 1931 letter in depth. There’s no basis for thinking it wasn’t straightforward.