In honor of Father's Day and in celebration of the exhibition Ralph Fasanella: Lest We Forget, Eye Level asked the artist's son, Marc Fasanella, about his father's work, life, and legacy. Take a look at Fasanella's other artworks in American Art's exhibition.

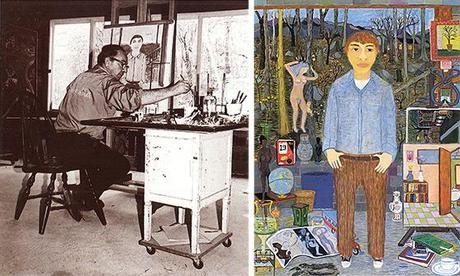

Left: Ralph Fasanella in his studio painting Marc's World, about on his son. Right: Marc's World by Ralph Fasanella. Both images courtesy of Marc Fasanella.

Eye Level: As we celebrate the exhibition Ralph Fasanella: Lest We Forget, as well as the 100th anniversary of your father's birth, what do you see as your father's strongest legacy?

Marc Fasanella: I believe he will be remembered foremost for his large political canvases. He chronicled many of the seminal events of his lifetime: the struggle for a living wage and an eight-hour workday, the cold war, the execution of the Rosenbergs, the assassination of John F. Kennedy, the sexual revolution, Watergate, and the collapse of the Soviet Union. As a self-taught painter he created imagery in an articulate, sophisticated, inventive and unique way. Since he taught himself painting he was constantly trying to master the mathematical perspective discovered by Renaissance painters. As a result his best canvasses have several perspectives and modes of scale, creatively unified through the application of sophisticated color choice, texture, and visual metaphor. He was this incredible combination of outwardly working class and inwardly deep intellectual.

EL: Marc, you're a professor of ecological art, architecture and design at Stony Brook University as well as a curator; are you also a painter?

MF: Although my feet are larger than his were, his were awfully large shoes to fill and I never tried. When I studied art, architecture, and design in college I picked up a brush a few times but I could tell I didn't feel the passion for that form of communication in the way my father did. He didn't "know" how to paint. He painted because he was compelled to. He couldn't stop the ideas swimming in his head from exiting through his fingers. My father was a passionate guy and he poured out that passion in many ways, but once he began painting that was his primary form of release.

I inherited his passion for politics and a life of the mind but my strengths lie in being able to articulate the ideas that swim in my head verbally, in writing, and in carefully constructed installations. I also have a nearly obsessive need to use my hands. And the creativity that my father imbued me with has led me to try to balance a life of working with my mind, in the earth, and with wood.

EL: Since we're celebrating Father's Day today, how do you best remember your father?

MF: My father was an exceptional guy. My mother always said that if he got on a crowded elevator by the time he reached the fifth floor he knew everyone in the car and would most likely keep in contact over time with at least one of the people he met. You could put him in any situation and in any environment and he would find a way to talk to people. With workers there was an instant bond. They could tell he was one of them: a guy with dirty fingernails, a pock marked face, jiving sense of humor, and deep empathy and appreciation for the work they were doing. He wanted to know their story, to figure them out. He could talk to them for the briefest of moments and make them think, chuckle, share in his thoughts or he in theirs. He could live with all of them, invited them out for coffee or to share a cigarette. He could meet someone at a luncheonette and spend the entire day talking to and sketching them obsessively.

He was also smart, well-read and articulate in an old school New York way. One of his many intellectual friends was a history professor with a PhD from the University of Chicago. They would spend entire days at a local diner discussing history and progressive politics, sometimes joined by other professional intellectuals. His duality (working class empathies and "elite" intellectual depth) have pervaded my life and caused me quite a bit of existential angst over the years. I pursued the life of an academic but have always worked and thought as a blue-collar guy as well. It took me up until my mid-forties to feel fully comfortable in my skin and to understand the strength that lies in being able to fully empathize from both a working class and elite perspective. I have much to thank him for in that.

EL: Did you two have any father and son rituals such as going to a museum, a ballpark, or the movies together?

MF: From my earliest recollection I think of my father treating me as a full equal. To him I was a guy to knock around with and explore the world, discuss politics, and appreciate life. When I was a young, on a day off he would take me to his gas station, to the Fulton Fish Market, to his sister's apartment for food and conversation, to textile mills in Lawrence, Massachusetts and treat me as a completely normal part of his everyday life. The two of us often ate meals together (I cooked, even as a kid), played cards, and did what most people would describe as "hung out." We wouldn't do anything special as a ritual but he was profoundly present as a father every moment I was with him.

As long as I can remember he called me "old man" and would ask my opinion on truly important matters perplexing him, taking my suggestions at full value. When he had to admonish me he would appeal to my reason and often end with "you're smarter than that old man." Of course there were times we disagreed but even if he threw a string of expletives (an object only once) at me, I knew they were propelled by love.

EL: He wore many hats and worked many jobs before devoting himself to painting full time? What do you remember about this time?

MF: My father tried his hand in his father's footsteps as an iceman with a route in New Rochelle, New York; as a truck driver; as a volunteer in the Spanish Civil War with the Abraham Lincoln Brigade; as a machinist's apprentice; a union organizer; and as a gas station owner. These experiences gave him a worldliness and a basic knowledge of how to use his hands I found impressive as a kid. But to me, my father was always a painter. I was born when he was fifty. I'm turning fifty in August and have a 14 year old son and an 18 year old daughter. I can't imagine embarking on fatherhood at my age. By the time I turned 14 he had sold the gas station and devoted himself full-time to painting.

EL: Did he have a studio in the house and were you and other family members welcome?

MF: I came of age in a home where my father was truly able to pursue his creative muse. Some days he would spend in deep intellectual conversation with a friend; some in search of inspiration at diners, union halls, or just "out in the world;" and many in his home based studio in the impassioned pursuit of a completed painting. I loved to watch him work, he kept a small bed in his studio and I often read, daydreamed or napped on that bed. He also had an old drafting table that he rarely used and by the time I reached college it was a place I could spread out my ideas and think a bit. He had a great ancient stereo on which he played both 78 and LP jazz and opera records. I loved that music! I still have and listen to his LP's.

When I became an accomplished carpenter in college he began to enlist me in the perpetual evolution of his studio. He collected references for all of his paintings. And between working on one series of paintings and another he would reorganize his materials and adapt the wide-ranging collage of references that covered the walls and surfaces of his studio.

I believe my sister spent much time in my father's studio when she was young. My mother would visit to admire and discuss whatever he was working on. But to me my father's studio was a sanctum where I could watch and marvel at the emotion and intelligence that poured out of him onto canvas.

EL: What artists did your father admire?

MF: My father collected art books and read widely about art. He was conversant about all of the impressionists in particular, but he was a devotee of Van Gogh. You can see that influence in the way he depicts skies and models the surface of his buildings. His early work had an incredibly deep impasto (paint thickness) but his mature work resembles Impressionist impasto. He was a profound admirer of Diego Rivera and loved other Mexican painters such as Zuniga. You can clearly see the influence of Rivera in my father's most dynamic political paintings.

EL: Did your father tell you stories about your grandfather who is depicted in many works as "The Iceman"?

MF: My father's relationship to his father is hard for me to fully understand; he was close to him, but as an observer. He depicted his father in several paintings as a man crucified, died having suffered as Christ has been depicted, long suffering, and little-understood. As a young boy my father rode on my grandfather's horse and wagon delivering ice to the many tenement dwellers to whom a refrigerator was a luxury they could not afford. He told me about the long days he would put in with his father walking up three or more flights of stairs with a large block of ice on his shoulder.

My father depicted his father to me as being a hard man who had a truly hard life. The marriage between my grandparents was also difficult and according to my father, since my grandmother was the intellectual superior, my grandfather would vent his frustrations with his marriage and his life upon his horse. From what my father told me my grandfather left his marriage, his children, and the United States a broken man. In the painting Family Supper there is an ice bucket in the lower left-hand corner on which is written "in memory of my father Joe - poor bastard died broke - and to all Joes who died same - broke"

EL: How do you want people to react when they view his work?

MF: Slow down, look intently (up close and from a few steps back), think in context, and find what is relevant to our time and to the human condition. Find what things he says in paint that outrage you, inspire you, enliven you, and what aspects of life you can celebrate and carry them forward.

EL: Your father is quoted as saying "paint could talk." In what ways do his paintings speak to you today?

MF: I have studied some of these canvases my entire life. Every time I look at one of my father's complex political paintings I see something new. His most accomplished works reveal to me the promise and perversions of America; the history of prejudice, oppression, and wage slavery; and the power of opposition. They also show hope, the struggle for a more egalitarian society, the beauty, poetry, emotional resonance of icons with unvarnished political imagery, and persuasive metaphor. I have a dialog with these works that propels me forward as a progressive academic: that moves me to engage in and advance the pressing environmental and social issues affecting the human condition today.