I picked up James Gleick’s book Faster and read it slowly – something it says people rarely do anymore.

I picked up James Gleick’s book Faster and read it slowly – something it says people rarely do anymore.

The subtitle is The Acceleration of Just About Everything. I was hoping for some insight into the human condition as affected by modernity; our lives are radically different from what we evolved for. But the book reads more like a Seinfeld monolog than a sociology essay – a string of quickie observations, never connected into some over-arching theory or viewpoint.

Yes, in many ways, life has gotten faster. We all know that. But what does it really mean for us? Gleick seems unsure, ambivalent – the book’s tone is bemusement.

He even contradicts himself at times. One chapter (“Short Term Memory”) starts, “As the flow of information accelerates, we may have trouble keeping track of it all.” Gleick explains that the media on which information is recorded quickly becomes obsolete. Tons of data are on floppy disks and microfilms – but can you find the machines today to read them? Et cetera. This is indeed a real problem. Yet then Gleick says: “amnesia doesn’t seem to be [our] worst problem. This new being just can’t throw anything away . . . It has forgotten that some baggage is better left behind. Homo Sapiens has become a packrat.”

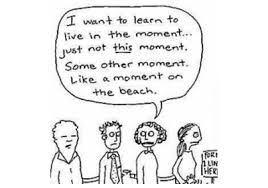

But perhaps such contradictoriness really is the essence of this book, in exploring our modern relationship with time. Gleick returns repeatedly to the concept of “saving time,” and how slippery it is. Talking about the genre of self-help books on time-saving, he says this (his emphasis):

But Gleick doesn’t really philosophize about the nature of time. In physics, it is indeed a tricky and elusive concept. There seem to be fundamental particles of matter, and maybe of space, but not of time; no unit is the limit of smallness in measuring time.

Time is the one thing which, once lost, can never be replaced. That might not matter much once we achieve immortality (or near-immortality); but as long as we know our allotment is limited, we value every minute. While people may have a lot of mis-judged values, the quest to save time is not one of them.

In my coin business, I used to mail out price lists (very laborious); then take down all the orders on the phone (even more laborious). Now I post the list on the web, and print out the orders. The time savings is great.

One point the book makes is that time has become a commodity, and a lot of our economy concerns its allocation. A business often tries to get customers to pay not just with money but with their time – “some assembly required” – thereby relieving the business of some costs.

Speaking of eyes glued to phones, Gleick quotes economist Herbert Stein: “It is the way of keeping contact with someone, anyone, who will reassure you that you are not alone . . . deep down you are checking on your existence. I rarely see people using cellphones on the sidewalk when they are in the company of other people.”

Reading this made me check the book’s publication date: 1999. Seems like ancient history now. Today many folks are fixated on their phones 24/7 – oblivious to people around them.

This is, again, a mode of existence radically different from our evolutionary antecedents. Some see it as dystopian; yet its extreme popularity tells us that it satisfies human needs in a very deep way. People always had a profound yearning for what their phones provide – but until recently, they just didn’t know it.