This is my entry for the Classic Movie Blog Association's Fall 2017 blogathon, Banned and Blacklisted, for links to all contributions, click here.

Marlene Dietrich in The Blue Angel

In 1930, 29-year-old Marlene Dietrich created a sensation with her breakout performance as cabaret temptress Lola-Lola in Josef von Sternberg’s The Blue Angel (Der blaue Engel), the tale of a straitlaced professor bewitched by a low-rent vamp. It was Germany’s first sound picture, produced in both German and English versions, and made for Ufa, the country’s once great and celebrated film company. Brand spanking new toast-of-Berlin Dietrich departed that city for Hollywood the morning after the film’s premiere. She was signed by Paramount with the hope she would be its answer to MGM’s Garbo, and she quickly rocketed to worldwide fame, earning a Best Actress Oscar nomination for her next performance, in Morocco (1930). Dietrich would stay in Hollywood, go on to apply for U.S. citizenship, and eventually achieve international stardom that would last until the end of her life.

Marlene Dietrich and Gary Cooper in Morocco

Marlene Dietrich’s departure from Germany in 1930 would be serendipitous in more ways than one. Germany had been struggling since its defeat in World War I in 1918 and the ratification of the punishing Treaty of Versailles in 1919. The Great Depression that made its way around the globe in 1929 further destabilized the country, doubling already high unemployment, and pitching the country into profound economic and psychological despair. This grim situation would help propel the rise to power of a once insignificant political faction, the fascist/racist/Anti-Semitic National Socialists, also known as the Nazis. By September 1930 the Nazi Party had become the second largest party in the German Reichstag(parliament).Dietrich, who was not Jewish, and her director/mentor Josef von Sternberg, who was, were long gone and far away in Hollywood when the Nazis took control of Germany in January 1933.

Heinz Ruhmann starred in many comedies during the Third Reich

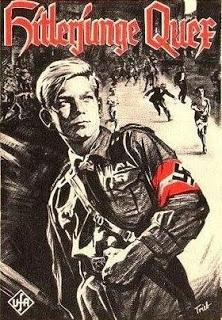

Under the Third Reich, the business of making movies was consolidated, with all aspects of film production brought together under Joseph Goebbels, head of the Reich Ministry for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda. Many Jewish and independent-minded actors, screenwriters and filmmakers hastily exited the country; some who did not move quickly enough would perish. Those deemed racially acceptable and who were willing to work with the Nazis remained. Goebbels was firmly convinced that movies were, “the most modern and scientific means of influencing the mass.” Though the majority of German films produced from 1933 – 1945 were distracting light entertainments, many others promoted Nazi dogma. Among the latter were Hitler Youth Quex released in 1933, a film that glorified Hitler Youth while condemning socialists and communists; Leni Riefenstahl’s documentaries Triumph of the Will (1935), extolling the Nazi Party’s 1934 Nuremberg rally, and Olympia (1938), exalting the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin; The Eternal Jew (1940), an anti-Semitic pseudo-documentary made following the Nazi occupation of Poland; and The Fuhrer Gives the Jews a City (1944), a propaganda piece depicting the Theresienstadt concentration camp as a near-utopia. Kurt Gerron, who directed this last film, was also an actor who’d had the featured role in The Blue Angel as the owner of The Blue Angel cabaret. A Jew, he had lingered too long in Europe and was eventually apprehended by the Nazis. Gerron directed the propaganda feature with the promise that his life would be spared; unsurprisingly, the relentlessly deceitful Nazis would later send him to Auschwitz where he was killed.

Hitler Youth Quex (1933)

On May 10, 1933, the most famous book burning in history occurred in university towns across Germany when a Nazi students’ association orchestrated the burning of more than 25,000 books by those judged to be “un-German” authors. Among those singled out was Heinrich Mann, the German writer whose book had been adapted to the screen as The Blue Angel. A proponent of democratic ideals who had become a popular novelist during the Weimar era, his standing would collapse once the Nazis seized power. Mann had just published an anti-fascist novel entitled Der Hass (Hate), and his books, along with those of his brother, Thomas Mann, and others were banned as well as destroyed in the bonfires. Mann had wisely fled Germany before the burnings and eventually came to America. Playwright Carl Zuckmayer had been a principal screenwriter on The Blue Angel. Once the Nazis took over, his work was also banned; Zuckmayer’s maternal grandfather had been born Jewish but converted to Protestantism. Zuckmayer also fled Germany and made his way to the U.S.

Emil Jannings in The Blue Angel

The Blue Angel's problems with the Nazi propaganda ministry went deeper than a banned author and screenwriter, however. Director Josef von Sternberg was not only Jewish, but he was also not German. In his 1965 autobiography, Fun in a Chinese Laundry, Sternberg writes that even prior to the film’s release in 1930, the officials at Ufa had become worried that “a German film had been made by a non-German, and that…the film did not seem to be German.” Sternberg goes on to say that Ufa feared the film might be seen as violating dearly held ideals of “German pride and morality,” and offend the public as well as the authorities. Ufa’s concerns were prescient. Though The Blue Angel proved to be a popular Weimar era hit, the Goebbels’ propaganda office of 1933 didn’t countenance films that reflected poorly on “the strict school system of Germany,” featuring errant and randy school boys, the antithesis of the idealized image of Hitler Youth, not to mention an unthinkable narrative about “a German professor going wenching in defiance of propriety.”The film’s male lead, Emil Jannings, who’d won the first Academy Award given for Best Actor in 1929, remained in the country and would continue to star in German films until 1945, but that was not nearly enough to keep The Blue Angel from being banned in Germany in 1933. It has been widely reported, though, that Herr Hitler kept a copy of the film for his personal enjoyment and watched it frequently.

Robert Donat and Marlene Dietrich in Knight Without Armor (1937)

A few years after the Nazi’s banned The Blue Angel, Marlene Dietrich was in London making Knight Without Armor (1937) with Robert Donat for Alexander Korda’s film company. While there, she was approached by Nazi operatives - some reports have it that Goebbels himself reached out to her - with the offer that if she would return to Germany, she could make any films she wished. But Dietrich was a staunch anti-Nazi and refused. Soon, all her films were banned in her homeland. She would ultimately renounce her German citizenship and become a U.S. citizen.During World War II Dietrich worked doggedly for the Allies, making anti-Nazi broadcasts in German, taking part in war bond drives and entertaining hundreds of thousands of troops in Europe and North Africa, often in areas dangerously close to the front. She also spearheaded and financed efforts to help Jews and others at risk get safely out of Germany. After the war she was awarded the Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian honor in the U.S., and was also the recipient of France’s highest tribute, the Legion d’honneur (Legion of Honor). In 1965 she was awarded the Israeli Medallion of Valor for her “courageous adherence to principle and consistent record of friendship with the Jewish people.”

After the Berlin wall fell in 1989, Dietrich left instructions that, upon her death, she be buried in Berlin, where she was born. And there she was interred, three years later, next to her mother.

~

The banning of Marlene Dietrich’s films in Germany during the Third Reich could have been predicted. She'd rebuffed what the Nazi’s considered a magnanimous offer, she was vocal in her objection to Nazism, she would work determinedly on behalf of their enemies and, unhappily for the Nazis, she was also the most prominent German-born film star of that time.But there was another country that took a more thin-skinned exception to a particular film of hers, and it was that country’s objection that would take the film out of theaters far beyond its own borders. The Devil is a Woman (1935) was the last of the films Dietrich and Josef von Sternberg would make together, and while the ban on her films in Germany was relatively short-lived, The Devil is a Woman would disappear for nearly 25 years.

Lionel Atwill, Marlene Dietrich and Cesar Romero, The Devil is a Woman

In 1935, Dietrich and Sternberg, both still working for Paramount, would undertake their seventh film in six years. A sly romantic fantasy, The Devil is a Woman was based on Pierre Louys 1898 novel The Woman and the Puppet. Sternberg planned to title the film Capriccio Espagnol (Spanish Fantasy) and conceived it as his “final tribute to the lady I had seen lean against the wings of a Berlin stage” as well as “an affectionate salute to Spain and its traditions.” It was Paramount production head Ernst Lubitsch who changed the film’s title, much to the chagrin of its director, to The Devil is a Woman.

Marlene Dietrich with Edward Everet Horton in The Devil is a Woman

A fantastically made up and costumed Dietrich portrays Concha, a beautiful but frivolous siren. Concha thoughtlessly torments her older, besotted patron, Don Pasqual (Lionel Atwill), a once respected, now disgraced – thanks to Concha - officer in the military. Arriving on the madly festive scene of Spain’s Carnaval is Antonio (Cesar Romero), a Spanish expatriate and friend of Pasqual. Although Antonio has been warned away from her, a romantic triangle involving Concha and Pasqual inevitably unfolds; it is not the first for Concha and Pasqual. The Devil is a Woman is an enigmatic and sophisticated dream of a film that can be interpreted variously, depending on the eye of the beholder. The Spanish government of 1935 beheld an offense. It was convinced that its military was being mocked as well as its governmental officials, especially as depicted by Edward Everett Horton in his turn as a bumbling provincial governor. Perhaps it wasn’t so much that Spain took the film too seriously, for this is a film of dark humor, but that the country was on the eve of a brutal three-year civil war and sensitive to even a hint of perceived criticism. The Devil is a Woman was banned in Spain and its government would go on to make diplomatic complaints in the U.S. that led to the film being withdrawn from circulation for more than two decades. All prints were thought to have been destroyed, but in 1959 the Venice Film Festival screened Sternberg’s own print to widespread praise. The Devil is a Woman stands today as one of the great Sternberg/Dietrich films, along with The Blue Angel, Shanghai Express (1932) and The Scarlet Empress (1934). Parenthetically, Luis Bunuel, whose irreverent Viridiana (1961) had been banned in Spain for 17 years, used Sternberg’s source material, The Woman and the Puppet, as the basis for what would be his final film, That Obscure Object of Desire (1977). This film version of Pierre Louys’s tale would be submitted as Spain’s entry in the Best Foreign Language category for the Academy Awards that year; it took the Oscar as well as many other awards.

~

Be sure to check out all the great contributions to the CMBA's fall 2017 BANNED and BLACKLISTED blogathon

Click here for links to all blogathon entries