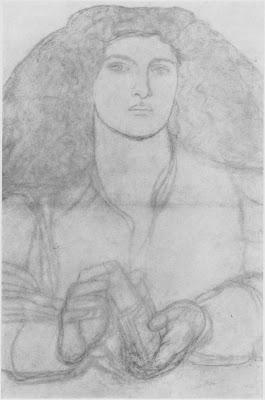

Fanny Cornforth (c.1860) Dante Gabriel Rossetti

In the beginning was Sarah Cox, born in January 1835 to William and Jane Cox of Steyning in West Sussex. She never hid her name or past when people bothered to ask her, so when Samuel Bancroft Jnr wanted to know where she was from she told him those same basic facts. By that point she had become Mrs Sarah Schott, married (for the second time) to John Bernard Schott after being widowed by her first husband, Timothy Hughes. For a while she had also been known as Mrs Hughes, all very straightforward. How then did we end up calling her Fanny Cornforth?

Fanny Cornforth and George Price Boyce (1858) Dante Gabriel Rossetti

It's partly the fault of this man, George Price Boyce, or at least he first recorded her as "Fanny", the speech marks being meaningful at moments like this. In his diary, 15th December 1858, Boyce records that he and Rossetti went to dinner then 'adjourned to 24 Dean Street, Soho, to see "Fanny". Interesting face and jolly hair and engaging disposition.' He soon drops the speech marks, merely calling her Fanny or F. or F.C. as in this entry from 11th April 1859 - 'Called on F.C. in Tennyson St. and gave her a silver thimble I had promised her, and made a slight pencil sketch of her.' At first it would be tempting to think 'FC' stood for 'Fanny Cornforth' but I think in this instance it is more likely to be Fanny Cox. So firstly how did she become 'Fanny'?

Fanny Cornforth (1859) D G Rossetti

Short answer is that we don't know. Much in the same way that we don't know why Elizabeth Siddal dropped the second 'l' off her original surname (Siddall) or why plain old Alice Wilding took the name Alexa, despite never actually becoming the actress everyone claims she was, but with Fanny it is assumed that she became a prostitute. Now, that is a bit of a presumption, but then being sexually active in return for money and presents, which is actually what the Victorians meant by 'prostitute', is a charge you could easily level at Miss Sarah Cox of Steyning. Boyce's diary is full of what he has given her in terms of gifts and meals, all without judgment. I think the main reason it is assumed that Fanny worked as a professional companion (rather than an enthusiastic amateur) is her name. 'Fanny' became synonymous with lady-parts because of the jolly eighteenth century novel Fanny Hill and so when Boyce placed the quotes around Fanny's name, it might have been because he suspected she was a working girl, but the quotes drop within days of meeting her and she just becomes plain Fanny. I've always wondered if she took the name of her last sister who died just as Sarah Cox became a young woman. Little Fanny Cox was the last child born and whose death at less than a year corresponded with that of her mother in 1847. Sarah had seen the majority of her siblings die over her 12 years and Fanny's death was the last before she left southern England, only returning to die herself sixty years later. It seems subsequent biographers preferred to believe a crude reality that she took the name of the bits that allegedly earned her living, rather than in remembrance of her sister. What does that say about biographers..?

Fanny Cornforth (c.1860) D G Rossetti

The 'Cornforth' part of her name is slightly easier to clear up. I urge you to read The Wife of Rossetti by Violet Hunt for the most breath-taking nonsense ever written about Fanny. According to Violet, Fanny's father, a Cornforth, came from good northern stock and her mother was descended from a union between one of Odin's ravens and a Saxon Maiden. Magnificent. Well, that clears that up then. For a less exciting version of events, I can offer the 1861 Census (sadly no ravens). When Sarah Cox married Timothy Hughes in 1861, she became Mrs Sarah Hughes, officially. Rossetti's subsequent letters to her are addressed to Sarah Hughes even if he still called her 'My dear Good Fan' in the letter. The 'Cornforth' part of her name appears briefly in her lifetime, namely in the 1861 census where Mr Timothy Cornforth, mechanical engineer, is recorded at 14 Tenison Street, Lambeth, living with his with Sarah, of Steyning, Sussex. Timothy Hughes had a complicated home life it seemed; his mother Margaret had married Timothy Hughes, whose son bore his name. After the death of Timothy Snr, Margaret went on to marry George Cornforth. Although Timothy Hughes Jnr was married as 'Hughes', he appears on his first census as a married man as 'Cornforth'. Thus Sarah (or Fanny) became Mrs Cornforth.

Fanny Sleeping (1860s) Dante Gabriel Rossetti

The only problem with this perfectly reasonable solution is that George Price Boyce refers to Fanny as 'Fanny Cornforth' before her marriage to Hughes, but as it is a mere few weeks before her marriage I am willing to bet that it is either a mistake in the transcribing of F.C. (Fanny Cox) to Fanny Cornforth, or that Fanny had assumed the name in preparation. I wonder if she took a fancy to it, and furthermore if she was the one who told the census taker what their name was. If Timothy Hughes had steadfastly stuck to his father's name in all other documents (marriage, 1871 census, death certificate), it seems out of character to suddenly take his stepfather's name for one census. If Fanny was already trying the picturesque surname out prior to the wedding it's not unreasonable that she gave them the title of Mr and Mrs Cornforth for their only census together.

The Card Player (1860-65) Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Unfortunately for Fanny the confusion and mystery over her name was assumed to be proof of her nefarious nature. Of all the other women to pose for Rossetti, Fanny is not the only one to fiddle with the name her parents gave her, yet her fiddling is the only one subsequent biographers have taken negatively. Whilst she is obviously ignored in commentary during his lifetime, a few of his early biographers did touch upon the subject of Fanny in the books that appeared in the twenty years after his death, which I will talk about tomorrow. In them she appears as either Mrs Schott (which at the time she still was) and Fanny Cornforth, sometimes as if the biographer has no idea they are one and the same person. It certainly seems that Fanny assumed her husband's names for different purposes and hung on to them longer than she hung onto him. Once Rossetti found himself alone in 1862, Fanny left her marriage and returned to her former lover's side.

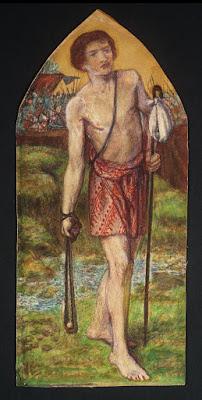

Figure of 'David' from The Seed of David (1858-64) D G Rossetti

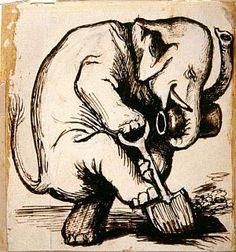

Elephant Burying a Jar (1874) D G Rossetti

Part of the narrative surrounding Fanny is that by 1865, when Rossetti replaced her with Alexa Wilding as his model, Fanny had grown fat. William Bell Scott referred to her as 'the creature with three waists' and the subsequent cartoons Rossetti sent her during his absences in the 1870s seem to infer that she had become elephantine in size, her long trunk removing objects she had no right to. It is hard to pick apart the modern prejudice from the contemporary nastiness in these descriptions, after all Bell Scott was also the man responsible for the story of how Fanny the Prostitute cracked nuts between her teeth and spat them at Rossetti, which is utter nonsense. In Helen Rossetti Angeli's Dante Gabriel Rossetti: His Friends and Enemies she states the painter 'shared the Italian predilection for fair women of ample proportions' and this seems in tune with his affectionate use of 'elephant', rather than derogatory. In fact the elephants began in 1863 when Fanny was still at the height of her modelling, with a sketch entitled Economies Elephantines showing a little elephant with a castle on its back (possibly referring to the Elephant and Castle which was near where Fanny and Rossetti lived at the beginning of their relationship) placing money in a safe. Fanny's tendencies towards self-preservation started early it seems, but then by 1863 she had already been dropped by Rossetti once in favour of another woman so I have to admire her far-sightedness to see that this was likely to be a pattern in her life if she remained with him.

Fair Rosamund (1861) D G Rossetti

An interesting, if sad, note in the whole business of Fanny's names is that when she was registered into Graylingwell Asylum, she was booked in as Sarah Hughes. At that point in 1907 she was a widowed Mrs John Bernard Schott but whoever it was that gave her name reverted to her previous married name. There is a note later that she is possibly Schott, but I wonder if the Schott family wished to remove themselves from her and did so by taking back their name. It seems unlikely (but not impossible) that Fanny would have reverted to Hughes, but maybe in her confused state she gave it. It is possible that after the treatment she had received from Rosa, her sister in law, Fanny fancied a bit of distance as well. When she died in 1909, she died as Sarah Hughes, 71, in Chichester. Possibly as she had such a fraught relationship with her real names, it's best we use the name she chose herself.

Fanny Cornforth (1863) William Downey

So Fanny Cornforth the Model she remained for her life and afterlife, but in private she was always 'Dear Fan' to the man who mattered most. It is a mistake to read too much into her names as half the time they are ones applied to her and often are titles applied to works of art. The problem with Fanny and her name is that it is used as proof of her other alleged crimes - lying, taking things that aren't hers, prostitution. If you start from a position where you believe someone to be a liar then an assumed name is seen as proof of that. Very quickly we turn that on its head and assume she is a liar as we know she lied about her name, and the circle is complete. It's always best to go back to the beginning and be very careful about what you are told. What's the betting that Bell Scott heard this story before he wrote his account of the three-waisted creature who spat nuts..? "Enter Fanny, who says something of W.B. Scott which amuses us. Scott was a dark hairy man, but after an illness has reappeared quite bald. Fanny exclaimed, 'O my, Mr Scott is changed! He ain't got a hye-brow or a hye-lash - not a 'air on his 'ead!' Rossetti laughed immoderately at this, so that poor Fanny, good-humoured as she is, pouted at last - 'Well, I know I don't say it right,' and I hushed him up." (William Allingham's Diary, Sunday 26 June 1864)Poor Fanny indeed...