A panorama of sylvan hills and ocean views surrounds artist Richard Brothers’s environmentally minded Orcas Island, Washington, home.

Project Brothers Residence Architect Atelier Drome ArchitectureA single-lane road winds its way up a densely wooded hillside to artist Richard Brothers’s home on Orcas Island, Washington. Dappled light and tendrils of fog filter through alder trees. It’s quiet except for the occasional sound of a car’s tires crunching on the gravel underneath. Then, after a sharp turn up a precipitous driveway, the road opens onto a rocky plateau topped by a long, lean house silhouetted against the sky. It’s as if the earth decided to produce an object of art to sit on this hilltop plinth, which was exactly the intent. As architect Michelle Linden says, “It is a site-specific, life-size sculpture.”

Natural and elemental shapes have inspired Brothers’s artwork since he started whittling pieces of wood as a ten-year-old. His recent drawings trace to-scale routes of rivers that he has walked alongside, while furnishings and textiles he’s designed spring from his interest in everything from ancient Cycladic figures to the pared-down aesthetics of Shakerism and Shintoism. It should come as no surprise that the house was born from his artistic inclinations—or that “the idea for the house came before I found the land,” he says.

A former Manhattanite who worked in finance to support his art, Brothers relocated to Seattle in 2007 when he commenced a search for his dream plot on which to build. Two years later, Brothers was introduced to Linden, a principal at Seattle-based Atelier Drome Architecture, and they immediately bonded over their shared visual palette. “Michelle and I have an alarmingly similar mental bank of images. She’d send me stuff; I’d send her stuff. It was great fun,” Brothers says of the design process.

Architect Michelle Linden worked with Brothers to create a minimalist house. Inspired by the inward-looking approach of Cistercian abbeys, Linden oriented the U-shaped structure around a courtyard.

Over years of discussions, the duo developed a concept that combined a studio and living area within an L-shaped space. Based loosely on sculptor David Smith’s notion of what Linden calls a “workingman’s modernism that’s quiet, obtainable, and clean,” the structure mimicked a shape that Brothers has used in his art for years. “It’s a simple, gabled form, like a child’s line drawing of a house,” Linden says. In 2011, Brothers found his perfect site—a ten-acre spot overlooking the ocean where his and Linden’s idealized object would fit nicely.

The finished structure, with its basic matte-black form, hews closely to the original design. In deference to the landscape, Linden made a few minor modifications, such as the addition of a slender building that holds a storage pavilion and gallery, along with a partially enclosed courtyard. The proportions of the three spaces—the shed, the studio, and the living room—reflect their functions: The shed is a tall and narrow utilitarian space; the studio is lofty and wide to hold oversize sculptures and canvases; and the living space is tight and polished, with six elegant glass doors stretching from floor to ceiling to frame the view.

Inside, the design beckons visitors through an intimate entrance room enclosed in white panels that Brothers describes as “a transition zone from outside to inside that allows all your haptic senses to chill out.” Turn right through an almost invisible door, and concrete floors slide through the quietly contemplative living-dining room, kitchen, and bedroom. Turn left, and the studio sprawls out, with its shelves of art supplies, walls pinned with art, and worktables brightly lit by lamps tucked into the ceiling beams.

Brothers forewent large windows and instead specified a series of glass doors—fitted with Walter Gropius–designed handles—along the house’s western side.

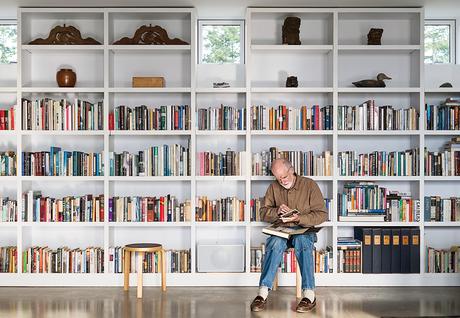

The entire place is specifically tailored for and by Brothers. “It’s only what I need and no more,” he says. A wall of custom bookshelves stretches the length of the living area. Furnishings, artwork, and rugs he’s created decorate the space, while near-seamless wall panels hide meticulously arranged dinnerware, vases, and linens. A few out-of-place pieces provide winks of wry humor, such as old-fashioned kerosene lamps over the dining table and an ornate, gilded 18th-century French mirror in the otherwise minimalist entryway.

This Spartan aesthetic extends to the material palette of whites, grays, and blacks chosen “to reflect the clouds, water, and rocks outside,” says Linden. Shots of blue and deep red from a throw blanket and pillows punctuate the space, and the book spines provide additional color. Sustainable aspects of the home further reflect its back-to-basics nature: Geothermal wells, solar panels, and radiant heat help the house achieve almost net-zero energy usage.

At the end of a day, Brothers gazes out his living room windows while a fire crackles in the wood stove. Outside, ferries slice the water below, while eagles and hawks soar above. Later, Brothers retreats to his studio to work on a painting. His house is an art object, one specifically designed around his creative pursuits. “There’s that sense amongst a particular group of artists—like Dan Flavin, Donald Judd, James Turrell—that sculpture is no longer about the space it occupies, but about the space you occupy,” Brothers says. “And that’s what these spaces are about for me on a day-to-day basis. My house is a sculpture for living.”

In the living area, Brothers sits on an Artek stool while perusing a selection from his library.

- Log in or register to post comments