British attempts at producing noir thrillers have tended to be a hit and miss affair, the greatest stumbling block generally being an inability to strike the right tone. The nuts and bolts are easy enough to put in place: the city setting, the night, the shadows and key lights, some criminal enterprise to provide a framework. However, British movies of the classic noir period (the 40s and 50s) struggle to escape the rigid class structures that remained firmly in place at the time. American films benefited enormously from the more flexible social structure of the country, which allowed filmmakers to blend in characters from a variety of backgrounds. Despite its best efforts, British noir tends to be forever trapped in a middle-class world and, consequently, loses something of the edge of danger that helped elevate pictures from across the Atlantic.

Eyewitness (1956) opens in these typically middle-class surroundings, with a minor domestic spat involving a young couple. Jay (Michael Craig) and Lucy (Muriel Pavlow) are two young suburbanites who have run into a bit of a crisis in their marriage. Jay is a guy who wants to live better than his income allows and has been accumulating a bit of debt buying stuff on credit. His latest acquisition, a brand new TV set, proves to be the straw that breaks the camels back though. Lucy is not at all impressed, such apparent profligacy failure to think of tomorrow going against the grain with her. In a foul temper, and threatening to leave for good, Lucy stalks out of the house to try to cool off.

While Jay sits home, toying with his new purchase and reflecting on the injustices of married life, Lucy’s wanderings take her to a movie theater. And it’s at this point the story starts to take shape. Jay’s feelings of frustration drive him out in search of a drink and some sympathetic male company, just at the moment Lucy’s conscience pricks at her and she decides to call him up. Getting no answer on the phone, Lucy is making her way through the theater when she chances upon a robbery in progress.

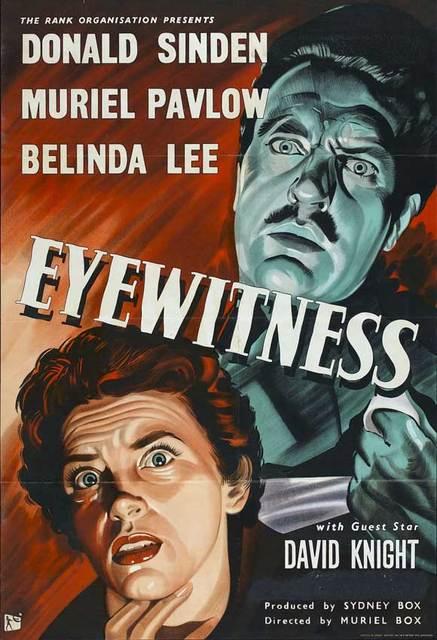

It’s Lucy’s misfortune to witness two men, Wade (Donald Sinden) & Barney (Nigel Stock), in the process of cracking the safe and roughing up the manager. Barney sets off in pursuit of the panic-stricken woman as Wade goes about settling matters with the ill-fated manager. Lucy’s terrified flight takes her out of the cinema, onto the street, and straight into the path of an oncoming bus. The situation leaves Wade and Barney in a quandary; is the unexpected witness going to live? And if she does, how much will she recall?

Wade reveals himself to be not only a cool customer, but a nasty piece of work to boot. His primary concern is his own self-preservation, and he coerces the meek Barney into falling in with his schemes. Wade has no intention of leaving any loose strands that may, in time, weave themselves into a noose to hang him. Following the ambulance that carries the comatose Lucy to a local hospital, Wade has in mind to dispose of this potential threat. Despite Barney’s protests, Wade takes it upon himself to stalk the now helpless Lucy and ensure nothing can be traced back to him. And so the bulk of the movie involves Wade’s attempts to gain entry to the communal ward where Lucy is taken. The suspense of the film derives from Wade’s determination, and increasing frustration, to silence this inconvenient witness. All the while, the net draws closer, time is running short and the opportunities grow fewer. Everything builds relentlessly towards a dramatic finale in a deserted and vaguely sinister operating theater.

Muriel Box was one of those rarities in classic era cinema, a female director. After writing some strong British movies – The Seventh Veil (1945) and The Brothers (1947) – she began directing in 1949. However, her career was closely linked to her husband, producer Sydney Box, and the break up of their marriage also signaled an end to her time behind the camera. Eyewitness sees Box making good use of the inherent suspense generated by the setting. A hospital at night is full of dramatic potential, the random comings and goings, the relative anonymity, that sense of disquiet aroused by the sight of mask-wearing professionals silently padding along starkly lit corridors. As the story progresses, Box ensures the tension grows in increments and the visuals reflect the increasing darkness of what we’re watching.

I think the biggest weakness stems from a basic flaw in the script. The success of pretty much any film, and especially a thriller, depends on having if not a hero then a recognizable figure that the viewer can identify with or root for. Eyewitness suffers in this respect; since it’s clearly intended that we should side with Lucy. However, she spends the bulk of the running time either unconscious or semi-conscious, effectively taking her out of the equation. There’s a similar problem with Barney, another whose presence ought to draw sympathy, but who ends up sidelined much of the time. In the end, we see things predominantly from Wade’s point of view, and he’s such a thoroughly bad lot, without a single redeeming feature, that it’s impossible to view him even in an anti-heroic light When it comes to the performances, Donald Sinden is pretty good as the twitchy killer with a slightly manic air. Still, the best work is probably done by Nigel Stock as the deaf safe-cracker whose dream of moving to New Zealand has seen him roped into a scheme that’s a whole lot more than he bargained for. Pavlow and Craig are so-so as the young couple whose marital tiff pitches them into a perilous situation, but there’s no great depth to their characterization.

In the final analysis, Eyewitness is a mid-range British crime thriller. The story is gripping enough but the lack of a sympathetic central character does damage it somewhat. The movie is available on DVD in the UK as part of a Donald Sinden box set from ITV. It’s a reasonably good transfer, presented in the correct 1.66:1 aspect ratio, though without anamorphic enhancement for widescreen TVs.

Note: I originally published an edited version of this piece as a Noir of the Week for The Blackboard.