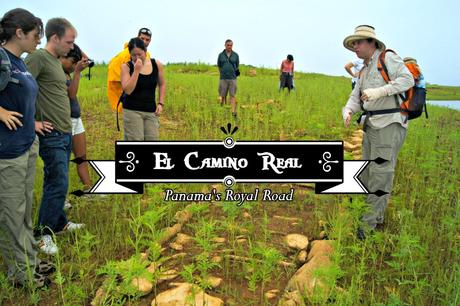

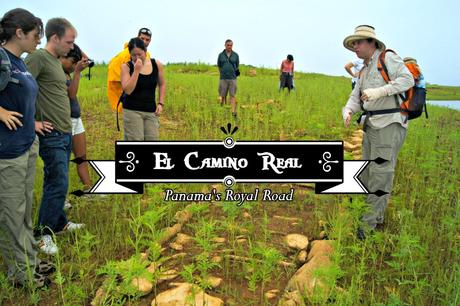

Once upon a time, long before Panama had its canal or a train, a road ran through the Panamanian jungle. This was not just any road, however. It was the lifeline that connected Panama City, on the Pacific coast, with its Caribbean trading partner, Portobelo. This historic road came to be known as El Camino Real de Panama, and it still exists today.

Day trip to El Camino Real

Always on the lookout for unusual things to do in Panama, we jumped at the chance to trek El Camino Real de Panama. Christian Strassnig, principal researcher and founder of the Camino Real Project,. was escorting the tour. What an opportunity!

Early one Saturday morning, about 20 of us boarded a small bus that took us to a tiny village on the edge of Lake Madden. Nueva Vigía has very little going for it besides one grocery store and access to Lake Madden – oh, and it has a latrine that only the most desperate, waterlogged traveler would even consider using. Our arrival was probably the most interesting thing that had happened there all week. I doubt they see that many gringos in their neck of the woods.

Down at the lake’s shore we climbed aboard a rickety-looking long wooden boat with a small motor, captained by a local. One woman balked and refused to get on because she thought it wasn’t seaworthy. (I don’t know why she was so concerned. We were, after all, wearing life jackets.) We all heaved a sigh of relief when Christian finally managed to convince her that it would do the job.

Off we went.

Lake Madden is actually not a lake. It’s a river that was dammed in the 1930s so that the Panama Canal would always have enough water to run in the dry season. The unfortunate side effect of the damming is that many segments of the historic road were submerged. For this reason, the boat had to carry us to assorted spots where the Camino Real emerged from the lake.

Some segments of the road were in better condition than others.

Where the road ran along the water’s edge the changing water levels had eroded the dirt under the stones, so many had moved. Actually, this made it easier to see the details of how it had been constructed. Flat stones buried on end along their edges anchor the actual cobblestones into place.

It is still possible to find artifacts from the colonial era in the lake’s eroded banks. Dan discovered a shoe from a mule, while I found a pre-Columbian spearhead. We left them where we found them so there would still be something interesting for future visitors to find. (Anyway, it would just be extra weight in my bag. It would probably end up forgotten, collecting dust in a box on a shelf. Our photos are enough of a souvenir.)

How Panama’s Camino Real began

After walking around for a while, we gathered in a shady spot to hear Christian explain the history of the Camino Real as well as how it influenced history. OK, I will admit that I vaguely remember learning about Spanish conquistadors as a schoolgirl, but Christian made it a lot more interesting than my teacher had. I finally understood why it matters.

When the Spanish began to conquer and pillage the Incas 500 years ago, the King commanded his explorers to find the shortest route from Peru to Spain. The result was El Camino Real, Spanish for “Royal Road” (or “the King’s Highway,” in English). This Royal Road was a four-foot-wide stone path, just wide enough for their mule trains to carry all their precious booty across Panama. The road began at the Pacific port in Panama City and crossed through the jungle to awaiting ships at Portobelo, on the Caribbean side.

Between 1519 and the mid-1700s Panama’s Camino Real brought untold wealth back to Spain and the church. Eventually, it fell into disuse and was forgotten. Today, most of it has either been reclaimed by the jungle or buried underwater (thanks to damming for the Canal).

Lunch with campesinos

When the sun was high overhead, we boated to Tranquila, a small lakeside peasant community, to have our noonday meal. This sure beat bringing a bag lunch! Christian came up with this idea because he wants to help the communities that aren’t in well-traveled areas. Although it’s not a part of his official job, he’s always looking for ways to expand tourism to lesser-known sites. It is a way to help these forgotten people benefit.

Men, women and children gathered to welcome and escort us to a long table where they had prepared a traditional lunch for us.

Christian had brought along a bag of ice (no electricity = no ice maker) so they could cool the drink they had prepared for us. They added water to lime juice and sweetened the mixture with raspadura. Raspadura is evaporated sugar cane juice and tastes slightly similar to brown sugar. It certainly made our drink taste different from the limonada sold in Panama City restaurants.

We had a choice between two traditional campesino meals:

As we often do, Dan and I asked for different dishes so we could sample both. Both had been cooked over a fire on the community stove and were really flavorful, though not spicy at all. (Panamanian food is rarely hot-spicy.) As we ate we learned that the men had spent the morning fishing for our peacock bass. Those chickens running about nearby had lost a few of their friends to our sancocho as well.

Panamanian sancocho, prepared campesino style.

Time for a fiesta!

After everyone had eaten, the village elder stood up. He announced that they had prepared a special treat: The boys and girls from their community would dance for us. Afterward, he promised, we would receive a surprise.

Tell you what, maybe they don’t have much by our standards but they sure know how to use what they have. As the music started we were surprised to see it was coming from a car stereo being powered by a car battery.

What was the surprise? The kids grabbed and brought us onto the dance floor while three men began to play toe-tapping traditional music on accordion, scraper and bongo. It was a memorable way to end our time with them.

Exploring remote Panama

Back on the trail again, two of the people on our tour blessed us with their knowledge: One was trained in geology and another knew all about reptiles and insects. This made our walk to the next site even more interesting. Christian led us to a limestone cave that was only large enough to fit about 10 people at a time. Adding to the experience a single small, brown bat flew over our heads as we entered, desperate to escape us, the unwelcome invaders. I am sure he didn’t appreciate having his sleep disturbed.

Our geology expert Brandon knew all about caves and explained how this one was formed and why one side was different from the other. We also visited a shelter cave. It was open on both ends and we were told the huge rocks laying about us had once been part of its roof.

Explore el Camino Real de Panama yourself

To promote tourism and offer tours of the Camino Real, Christian has since established Cultour. Cultour’s objective is to foster sustainable development of local communities along the Camino Real de Panama. Cultour also seeks to improve conservation of Panama’s wildlife (like jaguars).

Click here for more information about touring el Camino Real. Various tours are available, from one to four days in length, and it is possible to hire a private guide. Tours are in English, Spanish and German.

Tip: If you take this tour bring old shoes, rain gear and washable pants. It might rain and you will get muddy, but so what, this unique experience is worth it.

Inspired?

Save this for later. Pin to your Pinterest travel board.