Zack Ruskin: Aside from that whole World Series thing, what made you decide to write A Band of Misfits?

Andrew Baggarly

Andrew Baggarly: I always wanted to write a book, and for me, a baseball season works perfectly as a contained story. You have a roster full of characters of every origin and background who, come together, intersect for a summer of their life’s journey, then end up going wherever their careers lead them. There’s something almost fateful about that. So every season, I made sure to keep all my notes in case the year turned into something remarkable. The problem: My first 12 years as a beat writer, I never covered a playoff team. “On the Road to Mediocrity: Tales of the 2000 Anaheim Angels” was not a book anyone would want to read.I did cover Barry Bonds’ pursuit of the all-time home run record in 2007, and that was certainly a captivating story in more ways than one. But I didn’t write a book because it just wasn’t a celebrated event. I didn’t think a book on Bonds’ achievements would sell or be well-received. The Giants’ World Series season was quite the opposite. This was a celebration that had been pent up for 53 years. Even before I saw a million wildly happy people engulf the city for the victory parade, I knew the World Series championship would create a huge wave of interest in the Giants. Everyone wanted to know more about the team, and I was positioned better than anyone to tell these stories. And what stories! This was such an improbable team. Nearly everyone who put on a uniform was a compelling, interesting, emotionally charged figure.

Writing the book was personally rewarding, too. It was a way for me to preserve all my reporting and storytelling work in a more permanent form that baseball fans could access easily both now and years down the road. I’ve heard many people tell me they plan to read the book again every spring, just so they’ll never forget what happened in 2010. What could be more gratifying for an author to hear?

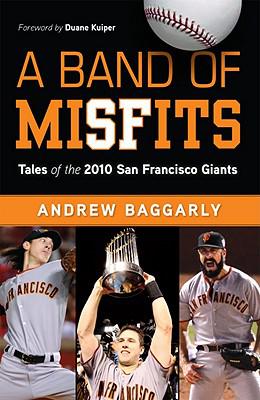

A Band of Misfits ($19.95)

ZR: There are so many threads in the narrative of the Giant’s 2010 season: the rise of Posey and Bumgarner, the additions of Burrell and Ross, Lincecum’s August, Sandoval’s sputtering second season. What was your method for covering everything you felt needed to be in your book without going all Bill-Simmons-Book-of-Basketball on everyone?AB: You’re right. There were so many stories to tell. I wanted to be comprehensive, but I also wanted the chapters to flow and move along. That was a challenge at times because of the way I felt I needed to organize the book. It’s a narrative that begins with the trade of Bengie Molina in early July and continues to the parade in November, but I’m constantly flashing back and fleshing out the background of these players as they step into their spotlight moments. I felt that structure, as long as I wrote carefully and clearly, would serve to break up all the blow-by-blow game details–and build the anticipation for them, too. Hopefully the games are recounted in an engaging way, but you can only read so much dramatized play-by-play before it just becomes play-by-play.

Some elements were underserved. I could have written a lot more about Giants ownership, or the move from Candlestick to AT&T Park. Although I devoted many pages to Willie McCovey and even Felipe Alou, I wrote very little about Willie Mays. There’s certainly more I could have done with Sandoval’s struggles, too. I wrote very little about spring training and I handle most of April and May in those flashback sections. At the very end of the book, I don’t really draw out the final inning of the World Series clincher, nor do I use gobs of words to gush about the parade.

Hopefully, though, all the people, places and moments that resonated the strongest with Giants fans are included in the book.

ZR: Did you find yourself scooping out portions of your columns, pumpkin-style, to amass enough text for ABOM, or did you opt to use solely fresh words?

AB: As Brian Wilson would say, “Sounds delicious.”

Because of the compressed production schedule, I didn’t have time for any additional reporting or interviews. Then again, I had been gathering material for the better part of a decade. Obviously, I had all my reporting, game stories, notebooks, features, blog posts, etc. from 2010. But I also was able to draw on material that I’d been writing and reporting about for the better part of a decade–including stories about Bengie Molina from when he was a rookie catcher in 2000 and I was covering the Angels beat that season. There were stories about Tim Lincecum that went back four or five years, which helped to show his personal journey.

I didn’t regurgitate this material, but I certainly repurposed it. Very loyal blog/newspaper readers might recognize a few turns of phrase, but I didn’t lift whole paragraphs or sections. And “amassing text” wasn’t an issue. My contract called for 60,000 words. When I hit that count, I’d only advanced the story as far as the first-round series against Atlanta. The final word count was somewhere around 95,000 words, I think.

ZR: Between yourself, Hank Schulman and Chris Haft, was there any internal discussion about who would “get” to write a book about the Giants, or were you the only candidate from the get-go?

AB: We are friendly and collegial even though we are competitors. But there wasn’t any discussion, really. Among our small beat crew, nobody had any more or less of a right to try to dash off a book. I just knew what I wanted to do, and I set the wheels in motion before the World Series even began. Chris Haft is finishing a book project now, by the way.

ZR: I can’t count the amount of times I’ve hit refresh in sheer panic, awaiting your next tweet to tell me how bad an injury was or whether Guillen would be in the line-up down the stretch. How do you feel Twitter has impacted sports reporting?

AB: The news cycle is no longer 24 hours. Now it’s 24 seconds–and faster than that, if my thumbs are quick enough as they dance on my iPhone screen.

Not long ago, I was responsible for a game story and notebook. That was it. Nowadays, I am responsible for those things, but I also have to be a wire service reporter, too. Whenever I find out any shred of news, however small, it’s being pecked into my iPhone. If it’s important enough, after I send a tweet, I’ll follow up with a more comprehensive blog post within a few minutes. Then I’m often writing the news for our iPad app. Finally, I’ll reshape that information to fit the notebook for the newspaper. And after I file several versions of the game story, one quick hit for the web and then the write-thru with quotes and the latest information, I usually write a postgame blog that’s very freeform and reads more like a column. There’s more analysis and some light opinion in there. That can end up being 1,500 words, depending on my level of sanity and energy. So I’m doing what used to be the work of three people–wire service reporter, beat reporter and columnist. Somehow, I have to find time to actually report the beat, too.

I’m not saying we had it easy back when I only wrote my pieces for the newspaper. It takes a lot of legwork to report accurate, relevant news and provide context and analysis in those pieces, as only a beat reporter can do well. Your work isn’t just measured in column inches.

I guess this is my fear: That the demands for immediacy–and the time spent repackaging information to fit various media–will wear out reporters to the point where they lack the time or energy to actually report their beats, talk to sources and track down information that is complete and accurate.

ZR: There are so many choices manager Bruce Bochy made in September and the post-season that had to go right for the Giants to win the championship. Does he deserve credit for the “magic” his team produced in that run, or was in more realistically a mix of luck, chemistry and determination (because some of those choices seemed crazy bad at the time)?

AB: They say luck is the residue of design, but the Giants roster was thrown together and rebuilt out of necessity during the season. So yes, of course, there was a lot of luck involved. But I don’t believe chemistry is something that happens by chance, and Bochy had a lot to do with creating that chemistry.

He knew he’d need contributions from the entire roster to survive a 162-game schedule, including people the fans wanted pushed out the door. So he didn’t quit on players, which drove many fans crazy during the season as he stuck with underperforming veterans like Aaron Rowand or Edgar Renteria. Bochy doesn’t show signs of fear or panic. I think players can sniff that a mile away from their manager, and it affects the way they play. They can let the game get too fast and that’s when they make mistakes. So there was great value in Bochy’s steady personality and leadership

Yet when the postseason started, you saw Bochy managing with a sense of urgency. What other manager would throw three-fourths of his playoff rotation in a non-elimination game? That’s what happened in Game 6 in Philadelphia.

In the end, Bochy knew he could trust someone like Renteria to stay with himself, even though he looked physically done for most of the season. Amazingly, he became the only World Series MVP in Giants franchise history. He doesn’t get that opportunity unless Bochy entrusts him with it.

ZR: What moment, in hindsight, most purely defined the season the Giants had last year?

AB: The best, most entertaining overall game was probably the Game 4 victory over Philly in the NLCS. It was such a back-and-forth affair. But in hindsight, I’d say Renteria’s three-run home run in the clincher at Texas. It was the moment you absolutely knew the Giants would really and truly win the World Series. This was an unexpected team getting the big hit from such an unexpected player … it was storybook stuff. You’ll have to read the book to understand how improbable Renteria’s hit really was.

ZR: Did you know you wanted to be a sports reporter from early on? If not, what got you on the path to your current job with the San Jose Mercury? Your job strikes me as one of those careers that seems utterly amazing from the outside looking in, but must be really hard as a day-to-day grind.

AB: I wanted to be a broadcaster in college, and I still think I’d enjoy trying it someday. But I changed gears after an internship at a newspaper allowed me to cover pro and major college sports pretty much out of the box. It was a great opportunity to attend the venues and be around athletes I enjoyed watching. I liked the fact that print work was more tangible, too. If I expressed an idea, it had more permanence than a spoken word. It’s turned into a great career.

Yes, the baseball beat is a grind like no other. I can’t imagine there is another reporter at the Mercury News who averages almost 400 bylines a year. I’m on the road 120 nights a year, which means I’ve missed countless birthdays, graduations, etc. When my friends or family are free on weekends or nights, that’s usually when I’m at the ballpark. That’s why you see few reporters stay on a baseball beat for years and years. It requires too high a personal sacrifice. The tradeoff is that my office is the press box and my view is the field. That never gets old, nor do I ever take it for granted – especially given the state of the newspaper industry.

I’m not sure you could call any job in newspapers a dream job. This is not the world’s most secure industry, as you know. The optimists will tell you it’s a challenging business. The pessimists would call it a death spiral. I try to be an optimist, but I’m a pragmatist, too. For now, I’m grateful to anyone whose day begins with a newspaper hitting their porch with a thud.

ZR: Were you a Giants fan before you began to cover them? Are you now that you do?

AB: I was born in the Chicago area and grew up a Chicago Cubs fan. Maybe there will be “A Band of Misfits” book for Cubs fans. Check back in a few centuries.

Now that I cover the Giants, sure, I have an affinity for some of the players who are generally nice guys. But practicalities trump all. I don’t root for the team to win or lose. I root for quick games, no rain delays, no extra innings and no late lead changes. That makes me use my delete key a whole lot more than I’d like.

I think it’s OK for a reporter to hope for compelling stories to cover. The Giants certainly provided that.

ZR: If you could interview any sports great, living or dead (or living, but you could interview them when they were more alive), who’d it be?

AB: Heck of a question. The first names that jumped in my head were Jackie Robinson, Jim Thorpe and Jesse Owens–someone whose athletic impact also made an enormous social impact. But I’d probably pick someone fairly obscure, someone we just don’t know much about. Maybe Josh Gibson, the great and fabled Negro Leagues star. I’d bet he has a compelling and deserving life story to tell – one that has yet to be heard.

***