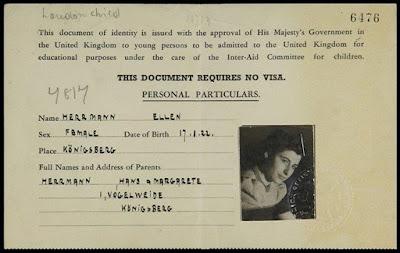

images: Two residents of Königsberg (now Kaliningrad)

images: Two residents of Königsberg (now Kaliningrad)Vast numbers of words have been written about the atrocities of the twentieth century -- about the Holocaust, about Stalin's war of starvation against Ukraine's peasants, about the Gulag, and about other periods of unimaginable and deliberate mass suffering throughout the century. First-person accounts, historians' narratives, sociologists' and psychologists' studies of perpetrators' behavior, novelists, filmmakers, and playwrights, exhibition curators ... all of these kinds of works are available to us as vehicles for understanding what happened, and -- perhaps -- why. So perhaps, we might agree with Zygmunt Bauman in an early stage of his development and judge that the job has been done: we know what we need to know about the terrible twentieth century.

I do not agree with that view. I believe another perspective will be helpful -- even necessary -- if we are to encompass this century of horror into our understanding of our human past and be prepared for a better future. This is the perspective of the philosopher -- in particular, the philosopher of history. But why so? Why is it urgent for philosophy to confront the Holocaust? And what insight can philosophers bring to the rest of us about the particular evils that the twentieth century involved?

Let's begin with the question, why does philosophy need to confront the Holocaust? Here there seem to be at least two important reasons. First, philosophy is almost always about rationality and the good. Philosophers want to know what conditions constitute a happy human life, a just state, and a harmonious society. And we usually work on assumptions that lead, eventually, back to the idea of human rationality and a degree of benevolence. Human beings are deliberative about their own lives and courses of action; they want to live in a harmonious society; they are capable of recognizing "fair" social arrangements and institutions, and have some degree of motivation to support such institutions. These assumptions attach especially strongly to philosophers such as Aristotle, Seneca, Locke, Rousseau, Kant, and Hegel; less strongly to Hobbes and Nietzsche; and perhaps not at all to Heidegger. But there is a strong and recurrent theme of rationality and benevolence that underlies much of the tradition of Western philosophy. The facts about the Holocaust -- or the Holodomor, or the Armenian genocide, or Rwanda -- do not conform to this assumption of rational human goodness. Rather, rationality and benevolence fall apart; instrumental rationality is divorced from a common attachment to the human good, and rational means are chosen to bring about suffering, enslavement, and death to millions of individual human beings. The Holocaust, then, forces philosophers to ask themselves: what is a human being, if groups of human beings are capable of such destruction and murder of their fellows?

The two ideas highlighted here -- rationality and benevolence -- need some further explication. Philosophers are not economists; they do not and have not thought of rationality as purely a matter of instrumental cleverness in fitting means to achieving one's ends. Rather, much of our tradition of philosophy has a more substantive understanding of rationality: to be rational is, among other things, to recognize the reality of other human beings; to recognize the reality of their aspirations and vulnerabilities; and to have a degree of motivation to contribute to their thriving. Thomas Nagel describes this view of rationality in The Possibility of Altruism; but likewise, Amartya Sen embraces a conception of reason that includes sociality and a recognition of the reality of other human beings.

Benevolence too requires comment. Benevolence -- or what Nagel refers to as altruism -- is a rational motivation that derives from a recognition of the reality of other people's life -- their life plans, their happiness and suffering, their fulfillment. To be benevolent is to have a degree of motivation to care about the lives of others, and to contribute to social arrangements that serve everyone to some degree. As Kant puts the point in one version of the categorical imperative in Foundations of the Metaphysics of Morals, "treat others as ends, not merely as means". And the point of this principle is fundamental: rationality requires recognition of the fundamental reality of the lives, experiences, and fulfillment of others. Benevolence does not mean that one must become Alyosha in the Brothers Karamazov, selflessly devoted to the needs of others. But it does mean that the happiness and misery, life and death, of the other is important to oneself. Nagel puts the point very strongly: strict egoism is as irrational as solipsism.

But here is the crucial point: the anti-Semitism of the Nazi period, the dehumanization of Jews, the deliberate and rational plan to exterminate the Jews from all of Europe, and the racism of European colonialism -- all of this is fundamentally incompatible with the idea that human beings are invariably and by their nature "rationally benevolent". Ordinary German policemen were indeed willing to kill Jews at the instruction of their superiors, and then enjoy the evening singing beer songs with their friends. Ordinary Jews in the Warsaw ghetto were prepared to serve as policemen, carrying out Nazi plans for Aktion against thousands of other residents of the ghetto. Ordinary Poles were willing to assault and kill their neighbors. Ordinary French citizens were willing to betray their Jewish neighbors. How can philosophy come to grips with these basic facts from the twentieth century?

The second reason that philosophy needs to be ready to confront the facts of the twentieth century honestly is a bit more constructive. Perhaps philosophy has some of the resources needed to construct a better vision of the world for the future, that will make the ideal of a society of rationally benevolent citizens more feasible and stable. Perhaps, by once recognizing the terrible traps that Germans, Poles, Ukrainians, and Soviet citizens were led into, social and political philosophy can modestly contribution to a vision of a more stable future in which genocide, enslavement, and extermination are no longer possible. Perhaps there is a constructive role for political and social philosophy 2.0.

And there is another side of this coin: perhaps the history of philosophy is itself interspersed with a philosophical anthropology that perpetuated racism and anti-Semitism -- and thereby contributed to the evils of the twentieth century. This is an argument made in detail by Michael Mack in German Idealism and the Jew: The Inner Anti-Semitism of Philosophy and German Jewish Responses, who finds that negative assumptions about Jews come into Kant's writings in a very deep way: Jews are "heteronomous", whereas ethical life requires "autonomy". These statements are anti-Semitic on their face, and Mack argues that they are not simply superficial prejudices of the age, but rather are premises that Kant is happy to argue for. Bernard Boxill makes similar claims about Kant's moral philosophy when it comes to racism. Boxill believes that Kant's deep philosophical assumptions within his philosophical anthropology lead him to a position that is committed to racial hierarchies among human beings ("Kantian Racism and Kantian Teleology"; link). These concerns show that philosophy needs to be self-critical; we need to ask about some of the sources of twentieth-century evil that are embedded in the tradition of philosophy itself. Slavery, racism, anti-Semitism, gender oppression, colonial rule, and violence against colonial subjects all seem to have cognates within the traditions of philosophy. (In an important article that warrants careful reading, Laurie Shrage raises important questions about the social context and content of American philosophy -- and the discipline's reluctance to engage in its social presuppositions; "Will Philosophers Study Their History, Or Become History?" (link). She writes, "By understanding the history of our field as a social and cultural phenomenon, and not as a set of ideas that transcend their human contexts, we will be in a better position to set a future course for our discipline"(125).)

There is a yet another reason why philosophy needs to engage seriously with evil in the twentieth century: philosophy is meant to matter in human life. The hope for philosophy, offered by Socrates and Seneca, Hume and Kant, is that the explorations of philosophers can contribute to better lives and greater human fulfillment. But this suggests that philosophy has a duty to engage with the most difficult challenges in human life, throughout history, and to do so in ways that help to clarify and enhance human values. The evils of the twentieth century create an enormous problem of understanding for every thoughtful person. This is not primarily a theological challenge -- "How could a benevolent deity permit such atrocities?" -- but rather a philosophical challenge -- "How can we as full human beings, with our moral and imaginative capacities, confront these evils honestly, and have hope for the future?". If philosophy cannot contribute to answering this question, then perhaps it is no longer needed. (This is the subtext of Shrage's concerns in the article mentioned above.)

I'd like to position this question within the philosophy of history. The Holocaust and the Holodomor are events of history, after all, and history seeks to understand the past. And our understanding of history is also our understanding of our own humanity. But if this question belongs there, it suggests a rather different view of the philosophy of history than either analytic or hermeneutic philosophers have generally taken. Analytic philosophers -- myself included -- have generally approached the topic of the philosophy of history from an epistemological point of view: what can we know about the past, and how? And hermeneutic philosophers (as well as speculative and theological philosophers) have offered large theories of "history" ("Does history have meaning?" "Does history have direction?") that have little to do with the concrete understandings that we need to gain from specific historical investigations. So the philosophy of history that considers the conundrum of the Holocaust and the pervasive footprint of evil in the twentieth century will need to be one that incorporates the best thinking by gifted historians, as well as reflective deliberation about circumstances of the human condition that made these horrible historical outcomes possible. It must join philosophy and history. But it is possible, I hope, that philosophers can help to formulate new questions and new perspectives on the great evils of the twentieth century, and assist global society in moving towards a more harmonious and morally acceptable world.

One additional point is relevant here: the pernicious role that all-encompassing ideologies have played in the previous century. And, regrettably, philosophy often gives rise to such ideologies. Both Stalinism and Nazism were driven by totalizing ideologies, subordinating ordinary human beings for "the attainment of true socialism" or "Lebensraum and racial purity". And these ideologies succeeded in bringing along vast numbers of followers, leading to political ascendancy of totalitarian parties and leaders. The odious slogan, "You can't make an omelet without breaking eggs", led to horrific sacrifices in the Soviet Empire and in China; and the willingness to subordinate the whole population to the will of the Leader led to the evils of the Nazi regime. Whatever philosophy can usefully contribute in the coming century, it cannot be a totalizing theory of "the perfect society". It must involve a fundamental commitment to the moral importance and equality of all human beings and to democracy in collective decision-making. A decent human future can only be made piecemeal, not according to a comprehensive blueprint. The future must be made by ordinary human beings, not ideologues, revolutionaries, or philosophers.