While some of us still might imagine the conservationist as a fancy explorer discovering new species in a remote corner of the world, or collecting samples while drowning in mud, a growing portion of conservation science nowadays consists of asking people about their ideas and behaviours.

Needless to say, this approach produces a fair share of awkward, if not dangerous, situations. After all, who likes the idea of completing a questionnaire from the fisheries office, asking about compliance with harvest limitations or license fees? Or, even worse, who fancies being asked about the possession of illegally traded wildlife?

Many conservationists would really like to have this valuable information, but at the same time it is clear that these questions put people at great discomfort. This leads to biased estimates of important behaviours affecting conservation. This is where specialised questioning techniques can help.

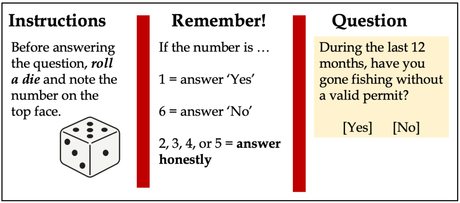

Specialised questioning techniques aim to prevent researchers, or anyone else, to trace back individual answers. Many do so by adding noise with a known distribution to individual answers. Then, when all answers are pooled, this noise is ruled out with statistical approaches. Noise can come from a randomising device (e.g. a die), like in the randomised response technique:

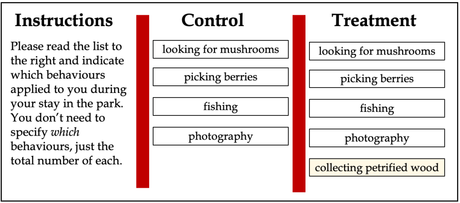

Individual answers can also be masked by asking respondents not to indicate if they engaged in a certain behaviour, but by asking them, out of a list of sensitive and non-sensitive behaviours, to indicate the number in which they engaged. This is the case of the unmatched count technique (a.k.a list experiments):

Not surprisingly, specialised questioning techniques are appealing to conservation biologists. Conservation social science needs to ask questions that often relate to sensitive behaviours, and many researchers have understood the advantage of asking them properly. While their first application in wildlife management dates back to the 1980s most of their use occurred over the last 20 years, being summarised in a popular review that was published in Biological Conservation in 2015.

Two years ago we decided that there was the need for an update of available methods: specialised questioning techniques are a fast-evolving field of research, which has greatly expanded since 2015. It was time to update the toolbox for conservation scientists. Our new review published in Biological Conservation, in addition to describing the state-of-the-art, found 14 advances of existing techniques, as well as 4 new techniques there were invented from scratch since 2015.

The state of the art is promising. Methods like the randomised response or the unmatched count technique saw the development of more efficient designs, requiring fewer respondents, and also enabling count estimates (e.g., number of poached individuals).

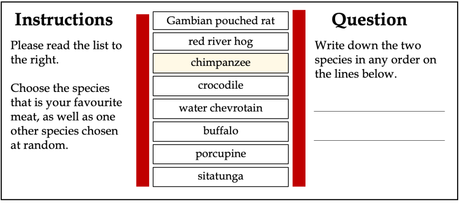

We also discovered new approaches such as the paired approach that asks respondents multiple questions simultaneously. This is a useful way to measure bushmeat consumption:

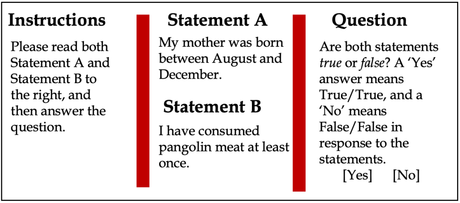

But probably the most significant development was in non-randomised techniques. These methods combine multiple questions, adding noise through one non-sensitive question whose distribution is known (e.g., birthdays). An example is the crosswise method:

These techniques seem to work well in practice because they do not require respondents to use any randomising device, have simple instructions, are relatively well-understood, and perceived as safe by respondents.

The conservation social sciences are here to stay. Increased access to the internet and the development of social networks like Facebook or Instagram open new possibilities for asking people conservation-relevant questions. We hope that our review will contribute to making conservation practitioners more aware of the many ways making questionnaires less embarrassing and more accurate.