A pilgrimage to Paris, to encounter Delacroix and Manet in the flesh, reaffirmed that we need not be committed to one way of working. A true artist does not bind herself to a ‘style,’ but searches endlessly after some elusive thing—let us call it truth, in an indulgently romantic fashion. Truth may be uncovered and approximated and represented in many ways, and despite the way we put our artists into categories, their work is rarely so easily defined, so one-dimensional.

Delacroix

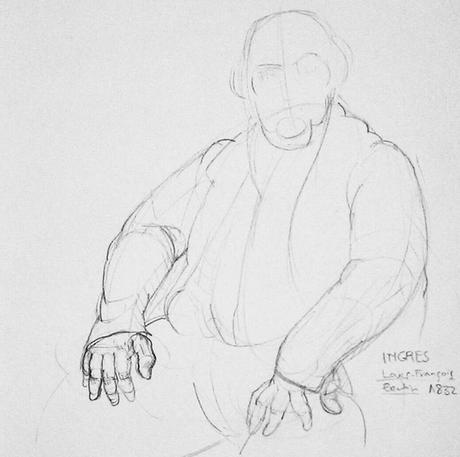

I saw Delacroix work of a very fine quality with well-defined contours and smoothly-modelled forms, and work of a more thick and fast quality, all the way up to very course, feverish and rough work, near incomprehensible smears of paint dancing upon the canvas. It brought me a devilish pleasure to see his most violent and spattered work hanging on the same wall as Ingres, classed together as ‘academic art,’ though as far removed from each other as imaginable. Ingres, with his linear emphasis; though his meticulously designed (and redesigned) lines are expertly integrated with his finely-modelled paint into eggshell-smooth rolling forms. The edges are airy, working in a magical unity with the forceful and clear lines. An unobservant viewer might be inclined to write off Ingres as formulaic and predictable, but finally encountering him face to face I am amazed at how his work breathes with such variety from within his preferred parameters. Crisp and deeply modelled spherical forms in rich ruby and emerald colours cloak his Joan of Arc in a convincingly medieval air, while a Venus basking in golden southern rays is treated in such a diffuse, hazy way that counters the severe artifice of the arc of her shoulders. Paint is put to such different use as the picture demands, and though he holds fast to his draughtsmanship, even this does not dictate the application of paint. Baudelaire (1972: 51) is quick to point out to the oversimplifying critic that color and line are not alien to each other: ‘You do not know in what proportions nature has combined in every mind the taste for line and the taste for colour, nor by what mysterious alchemy she produces the fusion between them, the result of which is a picture.’

(Copy after Ingres)

It is sheer madness to think that there is one way to apply paint, one method that defines us. The French are ever searching. They are testing the limits of paint, not out of ennui, not in a distracted pursuit of novelty, nor out of despair that everything has already been done. They are searching for the manner of expressing what they want to express. They are pushing paint to the very limits of its expressiveness. And perhaps they don’t succeed every time, but they certainly make many surprising breakthroughs.

Delacroix

Delacroix positively shimmers, in every way. His lines vibrate with urgency and vitality. The drawing alone is joyously bursting with life, exploding with energy. I take out my sketchbook and copy two women, crouched and one clasping the other, hair hanging tossed heavily over the head like an extra limb, extending the arch of the body. A perfectly designed foot curves with a lively flourish. My chunky drawing has found the Rubens in these draped figures, in their interlocking arms and their thick wrists and meaty bodies. Without a doubt, Rubens is flowing through these paintings, however loose Delacroix’s paint becomes—in the drawing and in the colours alike. For Delacroix’s colours vibrate as much as his lines. Hanging among Géricault in this huge hall, Delacroix’s color is punchy, judiciously applied, not overdone, but strong and resonant. Gold gleams and beads twinkle, hair shimmers like falling water and satin shines in its dampened way. A trembling wrist persuades me that Delacroix is able ‘to express simply by contour man’s gesture, however violent;’ while his glinting fabrics and glowing skin demonstrate his ability ‘to evoke with color alone what might be called the atmosphere of the human drama, or the spiritual mood of the creator’ (Baudelaire 1972: 361).

Delacroix

Perhaps only a painter could find pictures so unrelentingly brutal to be so abundant with life, because she cares more for the paint than for the subject matter. I reflect that it is almost a paradox to speak of Delacroix’s paintings being alive when his themes are almost exclusively death—though Baudelaire (1972: 359) shares my conviction that ‘he succeeded in translating the spoken word into plastic images, more full of life and more appropriate than those of any other creator of the same profession.’ Perhaps this pulsating energy comes from the realisation that life is but a vicious and frenzied struggle against death, which we are destined to lose.

Manet

In Manet I find the same ambitious range. His Olympia consists in such lovely drawing; all the lines lead you irresistibly to her crotch, where the most delicious drawing is concentrated in the expertly foreshortened hand, foreshortened by means of line, tone and colour, so meaningfully and powerfully conveyed in such a short stretch of painting. I think of the controversies Manet sparked, and I can imagine them as unintentional, unwanted controversies, the inescapable consequence of his search after truth. Olympia is certainly striking, but it is no provocative statement that makes her so compelling to a painter. The challenges to the male gaze and other art historical renderings of this picture seem remote and improbable when one stands before the canvas as a humble artist. Baudelaire (1972: 397) would remind us that ‘with two or three exceptions…the majority of artists are, let us face it, very skilled brutes, mere manual labourers, village pub-talkers with the minds of country bumpkins.’ A mere painter would see her task in much simpler terms than the intellectualising public might expect: she would simply be obliged to use all means available to make the image as cohesive and strong as possible. How could it be otherwise than that Manet reserve his best drawing, his soundest use of tone and colour, ‘all the means his craft gives him’ (Baudelaire 1972: 51), for this most fertile region of this modern nude? Formally, she is a strong, arresting, complete unity. Conceptually, she is shocking, because of what strong painting does when it mixes with the present. Can the present abide strong painting? Manet has not let me down.

Degas

In Degas I discover such variety of mark making, often within the one picture. Degas coaxes a self portrait, a luminous pair of hands, out of the surface, working the delicate transitions by near imperceptible degrees without compromising the overall form. He builds them up with increasing intensity from thin, rubbed-out raw umber, as if extracting them slowly from the mud. The humble raw umber underpainting and its gently undulating quality remains visible in places. Pictures grow out from the earthy and close but precise tones, the chroma gradually increasing with smears of rubbed-out opaque colour, and then a finishing touch of a thick and sure stroke of color at a yet higher chroma. And likewise, the dark tones are deepened with yet darker blues and blacks and browns. The unity is preserved: the variations stay in their place, ever subordinate to the greater mass.

Degas

And I enjoy his alternating demands on the paint according to his intentions. The double portrait of himself and the top-hatted gentleman is arresting at a distance; the dark forms of the men come starkly to the fore, but their faces are finely treated, sympathetic to complex and restrained emotions, the creases of the eyes firm and clear but ever so slightly softened. A single, delicious specular highlight adorns one corner of the square end of the gentleman’s nose. His top hat is a perfect, straight extension of his proud head. Paris glimmers behind them, a positive mash of pale pinkish and bluish whites, somewhat abrasive up close, but remarkably effective. The textural contrast should be insulting to the vision, but this brash experiment has succeeded—against all expectations, the discord harmonises: the picture forms a striking unity.

Rodin

Rodin’s breadth strikes me just as strongly. Certainly I know of his harried surfaces, the presence of his fingertips in thick smatterings of clay. I know this look of frenzied concentration in his rough man-handling of the surface, this working and reworking that belies his countless reattempts at truth, so poorly imitated by those who equate unthinking sketchiness with ‘expressiveness’ devoid of content. But perhaps more unexpected was that sometimes he can be so slick and precise, that he can introduce the most gentle twist, an understated arc perceptible from all angles, though unbelievably slight. That he can be so anatomically careful, and model so accurately. He can magnify this naturalism to monstrous proportions, and subject the body to fantastic strains and tensions—the compression of a foot firmly planted but screwing into the ground, the push and pull of flexors and extensors in heavily-set legs. Yet he can confine all this physical anguish within a smoothly-modelled exterior. And then he can absolutely let loose and let these taught, herculean, muscular bodies melt into strong but somehow unreal creatures, human but somehow superhuman, more flexible, more arched, more sinewy; deformed by their suffering. In these overbearing figures one feels the lithe energy of the smaller, quickly-sketched maquettes that trickle down the Gate of Hell. They are overgrown mud-men, bent and twisted in the cruel hands of a merciless god.

Rodin

‘A good picture,’ opines Baudelaire (1972: 365-6), ‘faithful and worthy of the dreams that gave it birth, must be created like a world. Just as the creation, as we see it, is the result of several creations, the earlier ones always being completed by the later, so a harmonically fashioned picture consists of a series of superimposed pictures, each fresh surface giving added reality to the dream, and raising it by one degree towards perfection.’ And as creators, we must not fall into habit, and thus disengage from our work, but approach each work with fresh eyes. We must bring to it the knowledge that it demands, and ever try to augment that knowledge through our investigations. There is no one way of working, even if we are trying to get at the same truth.

Delacroix

Baudelaire, Charles-Pierre. 1972 [1842-1860]. Selected writings on art and artists. Trans. P. E. Charvet. Penguin: Harmondsworth, England.