Sign up for CNN's Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news about fascinating discoveries, scientific developments and more.

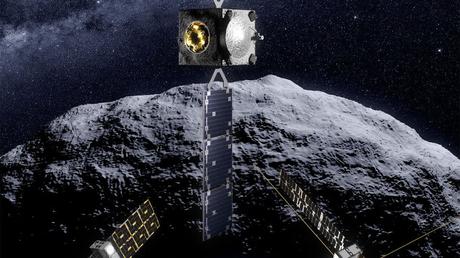

A European spacecraft and two shoebox-sized satellites have been launched to investigate the aftermath of NASA's DART mission, which deliberately crashed into an asteroid called Dimorphos and changed its orbit two years ago.

The European Space Agency's Hera mission lifted off Monday at 10:52 a.m. ET aboard a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket from NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida. The launch marks the first Falcon 9 flight since another rocket from the same family experienced an anomaly during NASA's SpaceX Crew-9 mission on September 29. The Federal Aviation Administration investigates the accident and clears the Falcon 9 to return to flight only for Hera. while the assessment is still ongoing.

The spacecraft and its two CubeSat companions are expected to arrive at the asteroid Dimorphos, and the larger asteroid it orbits, called Didymos, in late 2026. Together, the three spacecraft will conduct a crash scene investigation to solve the remaining mysteries about the doppelgänger. asteroid system, according to ESA scientists.

NASA planned the DART mission, or Double Asteroid Redirection Test, to conduct a full assessment of asteroid deflection technology for planetary defense. The agency wanted to see whether a kinetic impact - such as a spacecraft crashing into an asteroid at 13,645 miles per hour (6.1 kilometers per second) - would be enough to change the motion of a celestial body in space.

Neither Dimorphos nor Didymos pose a danger to Earth. Still, the twin asteroid system was a perfect target to test the deflection technology because Dimorphos' size is comparable to that of asteroids that could threaten Earth.

Astronomers have been using ground-based telescopes to monitor the impact's aftermath since the collision in September 2022, and they found that the DART spacecraft successfully changed the way Dimorphos moves, slowing the moon's orbital period. -asteroid has shifted - or how long it takes to make a single revolution. around Didymos - by about 32 to 33 minutes.

But many questions remain, including whether the DART spacecraft left only a crater or whether its momentum completely reshaped Dimorphos. And determining the exact composition of the twin asteroid system, as well as the consequences of the DART mission, could help space agencies further refine technology that could deter asteroids from impacting Earth in the future.

"Hera will close the loop by providing us in detail with the final outcome of the DART impact," said Patrick Michel, research director at the National Center for Scientific Research in France and principal investigator of the Hera mission.

On our way to a two-year journey

When the Hera spacecraft, about the size of a small car, reaches the twin asteroid system in October 2026, it will be 121 million miles (almost 195 million kilometers) from Earth. Didymos is a mountain-sized asteroid with a diameter of 780 meters, while Dimorphos is comparable in size to the Great Pyramid of Giza, with a diameter of 151 meters.

But first, Hera will fly by Mars in mid-March 2025, which will give the spacecraft the extra momentum needed to reach Didymos and Dimorphos two years after launch.

In addition to testing its eleven instruments, Hera will fly within 6,000 kilometers of the surface of Mars. Hera will also observe one of Mars' two moons, called Deimos, from a distance of 621 miles (1,000 kilometers).

Scientists think that both of Mars' small, clumpy moons could be asteroids captured from the main asteroid belt, located between Mars and Jupiter. Hera's flyby will collect data for Japan's Martian Moons eXploration probe. That mission, set to launch in 2026, will survey both of the red planet's moons and land a small rover on Phobos, collecting samples from that Martian moon that can be returned to Earth.

Next, Hera will arrive in orbit around the Didymos system in October 2026, where she will spend six weeks observing both asteroids to gain more details about their shapes, masses, and thermal and dynamic flybys, while identifying points of interest for future, closer will identify flights.

After the six-week survey, Hera will release its two CubeSats named Juventas, the Roman name for a daughter of Hera, and Milani. Milani is named in honor of Andrea Milani, a professor of mathematics at Italy's University of Pisa who died in 2018. Milani is known for creating the first automated system that calculates the probability that an asteroid could impact Earth in the future.

Juventas is equipped with a radar instrument that can see deep beneath the surface of the space rocks, while Milani has a multispectral camera to map minerals and dust on both asteroids. The instrument can capture a wider range of colors than the human eye can see, to determine the composition of individual boulders and the dust environment around them.

The CubeSats, which have their own propulsion systems, will use inter-satellite links to communicate with Hera and transmit their findings back to Earth, Michel said.

Over ten weeks, Hera will conduct observations that will bring her closer to the asteroid's surface, eventually coming within a radius of 1 kilometer. Multiple flybys are expected of the impact site created by DART on Dimorphos.

Ultimately, Hera could land on Didymos, which could serve as the end of its mission or a limited extension if it survives the landing, while the CubeSats could both make similar experimental landings on Dimorphos. None of the spacecraft are specifically designed for landing, but will slow down enough to operate cameras and instruments on the asteroids after landing, the agency said.

Investigating the aftermath

Humanity's most detailed glimpses of the twin asteroid system were short-lived.

The images captured by DART and a small satellite called LICIACube, which detached from the spacecraft to capture images of the collision and the resulting debris cloud, have fueled much of the impact-related research released since September 2022.

But when Hera visits Dimorphos, things could look very different, Michel said.

"What's most exciting for me is that while we have beautiful images of Didymos, Dimorphos and its surface taken by the DRACO camera on board the DART spacecraft before the collision, we already know that the same bodies and surfaces will have nothing to do. with what those images showed us when Hera makes new images," said Michel. "It still feels like discovering new worlds. And the cool thing is that we will know why they are new or different, since DART has given us all the initial conditions that led to their transformation."

Data collected by the mission can help scientists understand the internal structure of any asteroid. When DART collided with Dimorphos, a plume of debris extended more than 10,000 kilometers into space and persisted for months - enough to create the first human-made meteor shower that may be visible on Mars and Earth in the future.

Scientists would like to know whether Dimorphos is a rubble asteroid, held together by gravity with large voids in it, or a solid core surrounded by boulders and gravel, Michel said.

Understanding every possible aspect of Dimorphos is critical, mission scientists say, because if an asteroid of this size were to ever hit Earth, it could destroy an entire city.

Although the DART mission was a "tremendous success," Michel said, Hera is needed to understand the final outcome of the DART deflection test and measure its efficiency.

"I hope this can provide a source of inspiration for other missions dedicated to the defense of the planet and the exploration of the solar system," he said.

For more CNN news and newsletters, create an account at CNN.com