My daughter Elizabeth, 27, has worked for five years in the Mid-East for humanitarian organizations, currently for a consultancy much involved in Afghanistan. Wonderful, you might say. She herself is less sure — always engaging in critical self-scrutiny.

My daughter Elizabeth, 27, has worked for five years in the Mid-East for humanitarian organizations, currently for a consultancy much involved in Afghanistan. Wonderful, you might say. She herself is less sure — always engaging in critical self-scrutiny.

There’s much literature criticizing the whole foreign aid and development landscape, the road to Hell being paved with good intentions. Much aid has wound up serving to strengthen dictators. Other downsides may be less obvious. Send aid directly to schools and you relieve government of that expense so it can spend more on, say, weapons. Send used clothing and you undermine a nation’s own garment industry. And so forth.

Elizabeth and I have discussed such issues as relating to my own support for a Somaliland education project.

That makes me feel good. Is my Somaliland involvement really an attempt to buy myself those feelings? We’re actually programmed by evolution to feel good when doing good, it’s a mechanism to promote such behavior, thereby aiding group survival. So is there any such thing as true selfless altruism? But I’d maintain we are what we do. The doer of a good deed doesn’t delude himself believing he’s altruistic — he is in fact behaving altruistically. And his motivation is immaterial to the other beneficiaries of his action.

Elizabeth recently wrote a blog essay concerning the Oscar-winning film Learning to Skateboard in a Warzone, about an NGO project for Afghan girls — and an Al Jazeera article, Skateboarding Won’t Save Afghan girls.

Why put “liberated” in snide quote marks? America’s intervention did liberate them, did give them opportunities the article actually correctly characterizes. Though obviously Afghanistan’s problems were not all solved. Is that really the bar for judging any project’s worth?

Elizabeth says the real question is whether a program like the skateboarding —which does have real benefits — comes at the cost of other initiatives, which might have larger impacts. “Should we address the problems, or the symptoms of the problems — or both?”

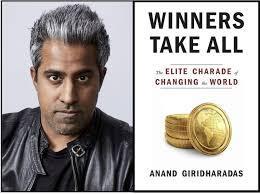

She cites a book, Winners Take All, by Anand Giridharadas, arguing that the business world is too focused on symptoms rather than underlying problems — and indeed those so focused are the very people benefiting from the system that perpetuates the problems.

Seriously? As if they somehow calculatingly orchestrated the whole global economic structure just so they could profit from the app? And does Giridharadas have a workable solution to the underlying problem he sees? No, he just wants other people to simply forgo their self-interest. Thanks a lot.

Casting the problem as the fault of villains is a kind of scapegoating all too prevalent (particularly in the left-wing economic perspective). But those who profit by hiring people for temporary work enable those employees to earn money by creating goods and services whose buyers value them above what they pay.

Elizabeth too largely disagrees with Al Jazeera and Giridharadas. She sees nothing wrong with addressing “symptoms” — while also working on “problems” — which may take decades if not centuries. These are not mutually exclusive. No reasonable person could view the skateboard film and think all Afghanistan’s problems are solved. Indeed, she considers it important to spotlight such successes. Whereas moralistic symptoms-versus-problems dichotomizing can make doing what’s merely feasible seem pointless.

Elizabeth’s main concern is with the impact one’s actions can achieve, and thus whether to target “problems” or “symptoms” — the “policy level” versus the “personal level.” But as for what any individual can do, she interestingly invokes the concept of “comparative advantage.” That’s an economics doctrine saying a nation gains from trading whatever it’s best at producing, even if other nations can produce that thing better. Applying it here would mean doing what one is best equipped or positioned to do. Better to have a modest success than an over-ambitious failure. But she also suggests a third option: start small and strive to scale up.

I think Al Jazeera’s analogy to palliative care is also fatuous moralizing. One is not usually able to achieve big-picture solutions. But regardless of what level you’re looking at, what matters is quality of life — for the many, or a few, as may be. Every one counts. Every improvement counts. Inability to go big doesn’t negate the value of the small. A cancer patient may not be cured but meantime palliating the pain is worth doing. Likewise for the Afghan skateboarding girls.

Don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good.